I. The Subversive Core of Comics

"Any startling piece of work has a subversive element in it, a

delicious element often. Subversion is only disagreeable when it

manifests in political or social activity."

- Leonard Cohen

In the 1960s American comics changed. They were always regarded

as shrill, cheap, and trashy, with dropping sales in the past

decade. Yet at their core, they became subversive, in tune with

the rising counterculture of the 1960s. This decade brought a

cultural explosion: questioning traditional modes of authority,

protests against the war in Vietnam, a vocal youth culture, new

music, widespread social tensions, liberated sexuality, women's

rights, experimentation with psychoactive drugs.

In his seminal work

Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art

,

Scott McCloud describes comics as "juxtaposed pictorial and

other images in a deliberate sequence, intended to convey

information and/or produce an aesthetic response in the viewer."

As an art form, they were much more than that; they were an echo

of the world around them. And in the 1960s they transformed

along two different lines: commercial comics and the "comix

underground."

How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way

By the 1960s "mainstream" comics were firmly set in the

superhero genre. DC Comics, the industry's top dog, with its

stable of superheroes such as Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman

was being challenged by upstart Marvel comics. The work of

writer Stan Lee and artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko subverted

the comics mainstream that was traditionally oriented towards

children. They introduced superheroes who appealed to older

readers, breaking convention with other archetypes of the time

by showing characters with personal flaws, who quarreled with

their peers, and who lived in the eventful world of the 1960s.

Figure 2: Black Bolt of the Inhumans in a panel from

Fantastic Four #59 by Jack Kirby (pencils) and Joe

Sinnott (inks).

In

American Experiences: Readings in American History: Since

1865,

Randy Roberts and James S. Olson wrote that "Marvel Comics

employed a realism in both characterization and setting in its

superhero titles that was unequaled in the comic book

industry."

Figure 3: Psychedelic panel from Silver Surfer #1 by

John Buscema (pencils) and Joe Sinnott (inks).

In comics series such as Fantastic Four,

Doctor Strange, and Silver Surfer, Kirby,

Ditko, and Lee plotted grand "cosmic" ideas about

extraterrestrial civilizations, different dimensions,

personified embodiments of abstract notions, whole human

cultures hidden from the world, and alien gods. Many of these

concepts were exaggerated ideas previously encountered in

science fiction, but the way the Marvel artists depicted it,

much of the imagery was psychedelic and on a cosmic scale.

The comics published at Marvel managed the then unique bridge

between the absurdly grand and the humbly human. Simply put,

Marvel comics were a breath of fresh air.

Drawing from the Underground

The second component of the one-two punch of the comics

renaissance of the 1960s was underground comix (yes, spelled

with an "x"). These small-press or self-published comic books

often covered socially relevant issues in a satirical manner.

Their art style flew in the face of the established superhero

comics, ranging from deliberately dilettante to classically

rendered or even caricature. Underground comix were not bound by

the restrictions of other printed media, often openly depicting

sexuality, explicit drug use, and violence.

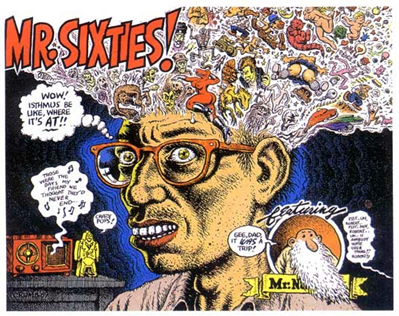

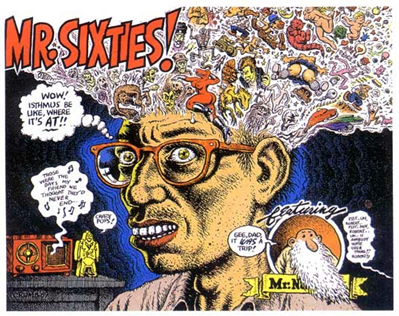

Figure 4: Piece drawn in ink by artist Robert Crumb from

The Complete Crumb Comics

Vol. 4: "Mr. Sixties!"

The main progenitors on the comix underground were Robert Crumb,

Gilbert Shelton, Trina Robbins, Gary Panter, Barbara "Willy"

Mendes, and many other artists who spread their work in the

counterculture scene.

The genre featured strips such as Frank Stack's

The Adventures of Jesus in 1962 and Gilbert Shelton's

Wonder Wart-Hog, as found in college-humor magazine

Bacchanal #1-2 in the same year. Robert Crumb

self-published Zap Comix in San Francisco in 1968. Many

titles covered subjects as widely varied as politics and

pornography.

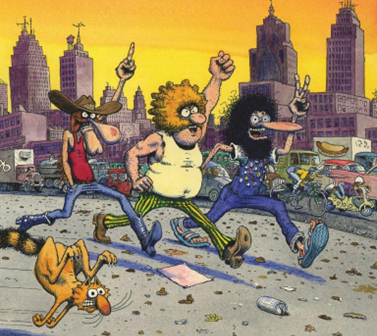

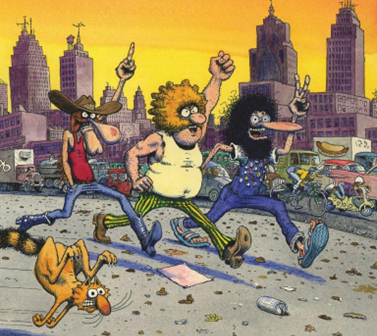

Figure 5: Gilbert Shelton's Freak Brothers.

Underground comix subverted the limitations of the comics medium

and brought a new energy and inspiration to the cultural

mainstream.

Technology and Art

To a certain extent, it is fair to say that drawing and

distributing comics is not merely a function of art but very

much of technology. It only became feasible to easily produce

and distribute comic books once the process of printing became

widely enough available and cheap enough to warrant it.

One of the reasons for the widespread adoption of comic books as

a creative outlet was that creating a comic book took far fewer

resources than other mediums. Making a movie back in the 1960s

was an expensive and time-consuming endeavor, and getting a film

distributed was often an insurmountable hurdle for fledgling

filmmakers.

To create a comic book, all you needed were pencil and paper,

pen and ink . . . and something to say, a story to tell. Of

course, if you wanted to touch the souls of your readers, you

also needed talent. Even in the 1960s, finding and paying for a

printer for the low print runs in black and white on cheap paper

was feasible, if not always easy. To get something printed in

color was far more expensive, and you would usually have to go

to an established publisher.

Underground artists could distribute their finished product

themselves by using the many record stores or comics specialty

shops in large metropolitan areas. Established publishers could

default to newsstand distribution or mainstream retail outlets.

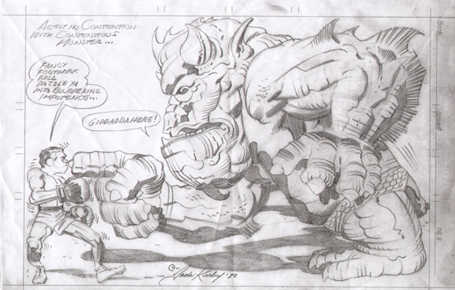

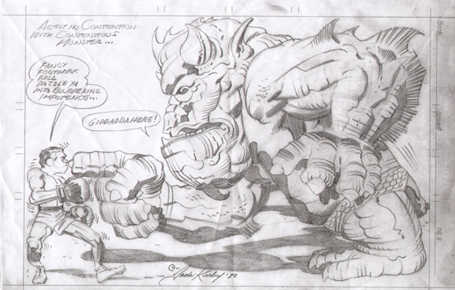

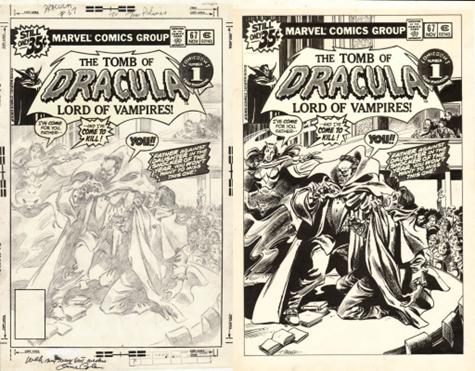

Figure 6: A pencilled comic panel before it was inked and

lettered (Jack Kirby, 1978).

No Creative Limits

While printing technology and publishing have evolved over time,

the core process of creating comics has not changed a lot. You

tell a story in panels, usually rectangular sections that

progress across the page with glimpses of what is happening with

characters, objects, and locations drawn in them. Exposition and

dialogue are lettered into boxes and speech bubbles. You even

have a mechanism to show the thoughts of characters as clouds

hovering close to their heads.

Potentially, it only takes a single writer-artist to create a

comic story. The creator thinks of a story plot and sketches it

out roughly, either as thumbnail images or directly on the page

where they will draw the artwork. Usually, the original artwork

is in a format much larger than the printed result; the process

of reducing it in print brings out the details.

While a single individual could do everything

themselves, and many have in the past, the process is most

likely split up among more creators. A writer would write the

plot and the dialog. A penciler sketches out the character,

settings, and locations in the panels on a page, focusing on

getting proportions and perspective right and telling the story

the writer describes in their script. The inker takes the

penciled pages and gives the pale lines weight, the depicted

objects and characters texture, and even corrects the occasional

lapse in the pencil. A letterer puts in the speech bubbles,

captions, and thought balloons and adds sound effects where

necessary. And finally, a color product requires a colorist.

Creating comics can be a very collaborative process.

Underground and independent comics did not always follow this

approach. They might produce comics alone or as a duo of

creators to come up with story and art collaboratively.

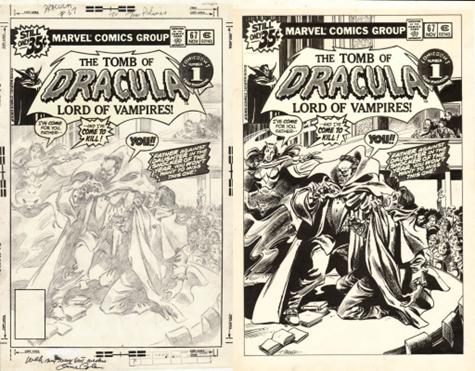

Figure 7: The cover of Tomb of Dracula #1 during the

production process.

Most importantly, what was depicted on the page was not limited

by budget or available locations and actors, as is the case in

filmmaking. Given sufficient time and talent, anything could be

drawn on the page, be it a vast space fleet, a rock concert with

thousands of people in the audience, a robot army, an alien

world, or a caricatured celebrity. Comics could be "artsy" or

actually artistic. They could depict high adventure or devious

drama; they could be juvenile or raunchy. And, of course, they

could show the high jinks and tribulations of superheroes.

Any story or genre could find its place on a comic's page, only

limited by the creators' imaginations. Given the right

technological advancements, comics not only were capable of

subverting genres but potentially, they might even subvert art

itself.

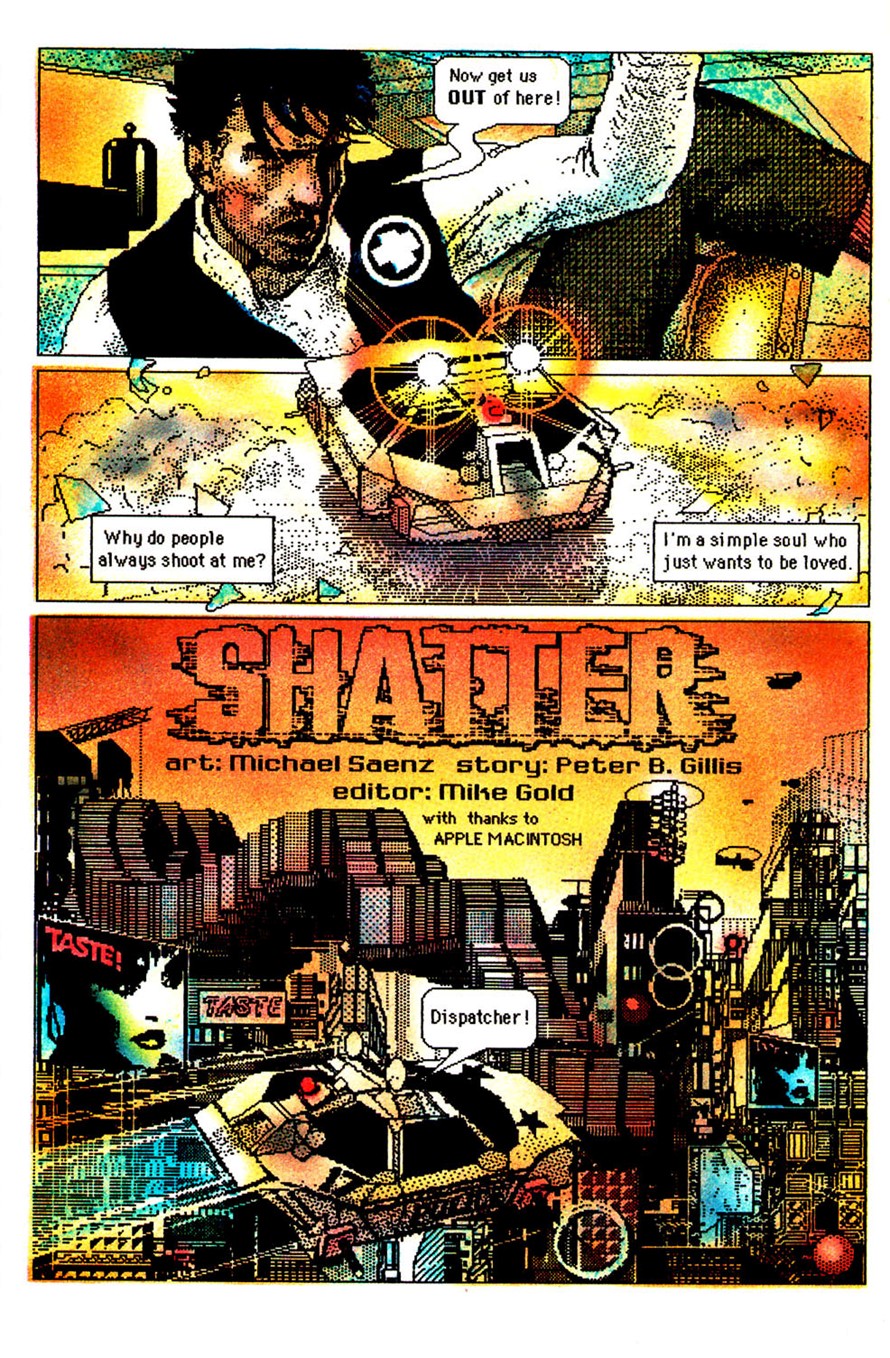

II. Shatter

The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our

souls.

- Pablo Picasso

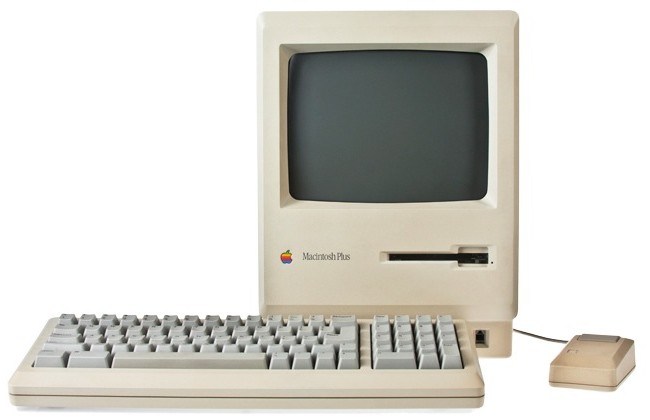

Nowadays, computers are prolific. Pretty much everyone has one

in their pockets in the shape of a smartphone. Some people even

wear computers. Digital technology is everywhere.

If we turn the dial back to 1984, we see that computers were

still thought of as a science-fiction device. While kids loved

their video games, adults regarded computers with awe. At the

time, few understood what they were capable of then or how

transformative they would be in all areas of life going forward.

Only two years prior, William Gibson had coined the term

"cyberspace." The writer had published his debut novel

Neuromancer, a book that led a wave of excitement about

the possibilities of computers. In 1984 Apple founder Steve Jobs

introduced the first Macintosh computer.

Colliding at the Cross-Section of Art and Technology

It seemed that the Apple Macintosh was destined for graphics

work, for art. At its launch, Apple made programs available such

as MacPaint and MacDraw. This opened up a world of possibilities

for artists and for computer-assisted art and design.

Throughout the history of comics, writers and artists have

experimented with the medium in a multitude of ways. They have

developed artistic techniques to change existing conventions

into something new. Through changes in the culture around them,

they have seen new perspectives and depicted the cognitive shift

in their work. In the early 1980s, comics grew stale and timid.

The mainstream titles such as The Uncanny X-Men and

The New Teen Titans had turned from the daring upstarts

to the status quo. Not only audiences but also the artists

producing comic books had a constant hunger for something fresh

and exciting.

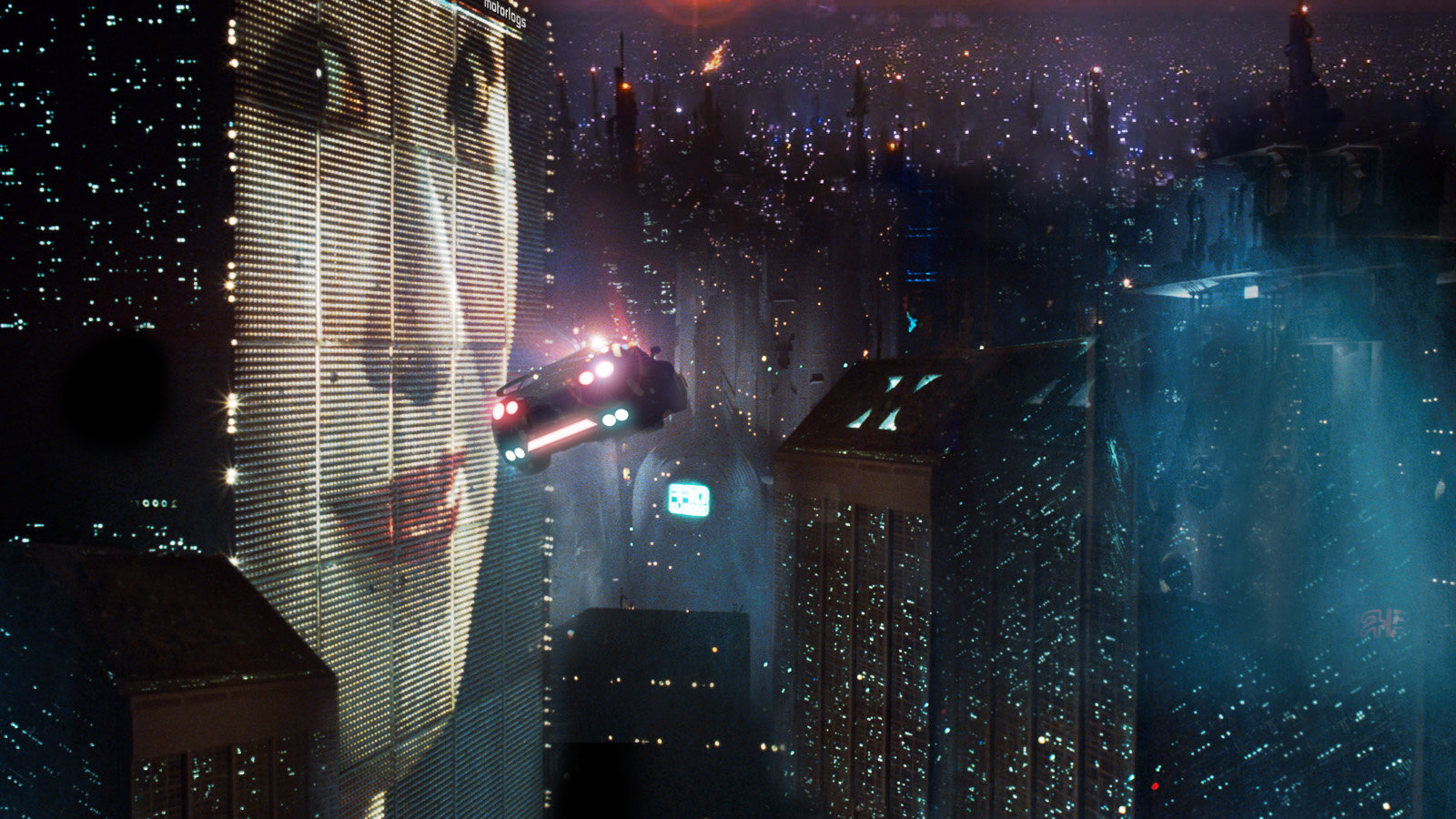

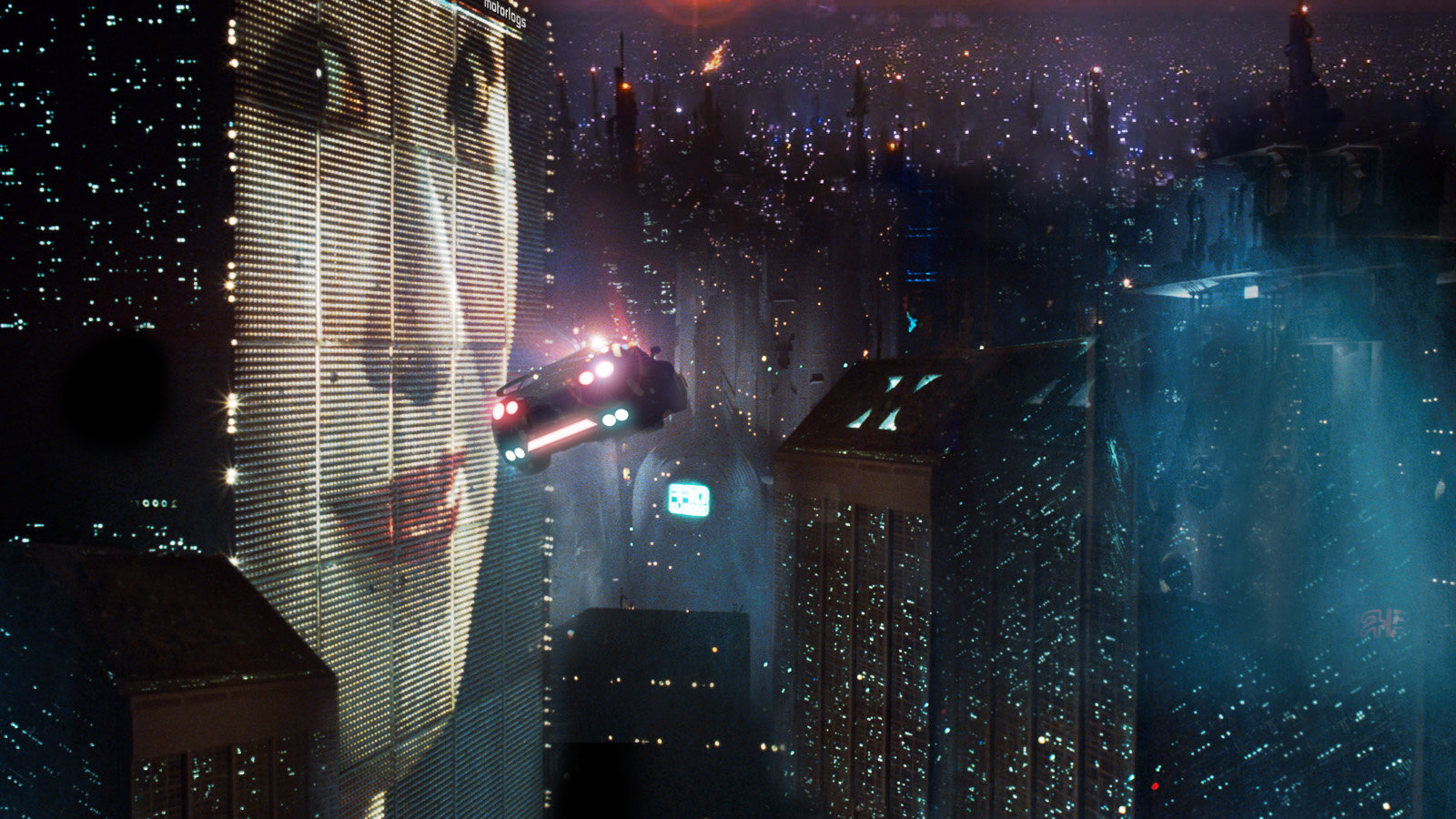

Figure 8: Still from Bladerunner, directed by Ridley Scott in

1982.

As William Gibson once said: "The street finds its own uses for

things."

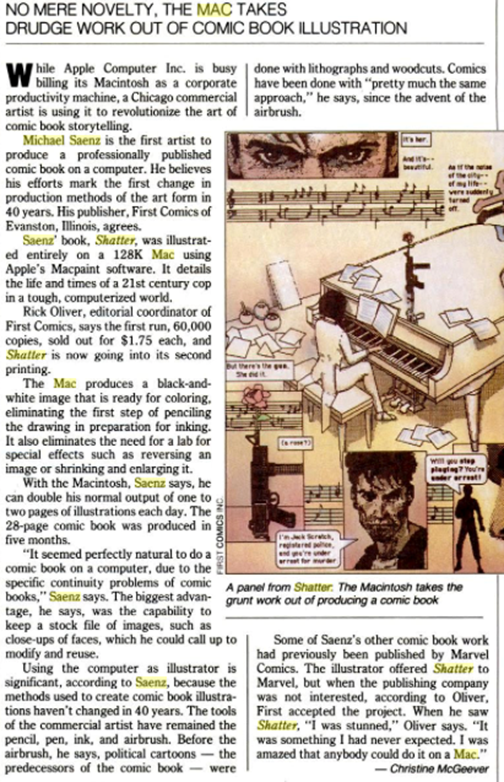

The advent of the first affordable graphics computer, the

zeitgeist of cyberpunk, and the hunger for new visuals and

storytelling collided at the cross section of technology and

art. In 1985 they converged to create Shatter, the

first digitally produced comic book.

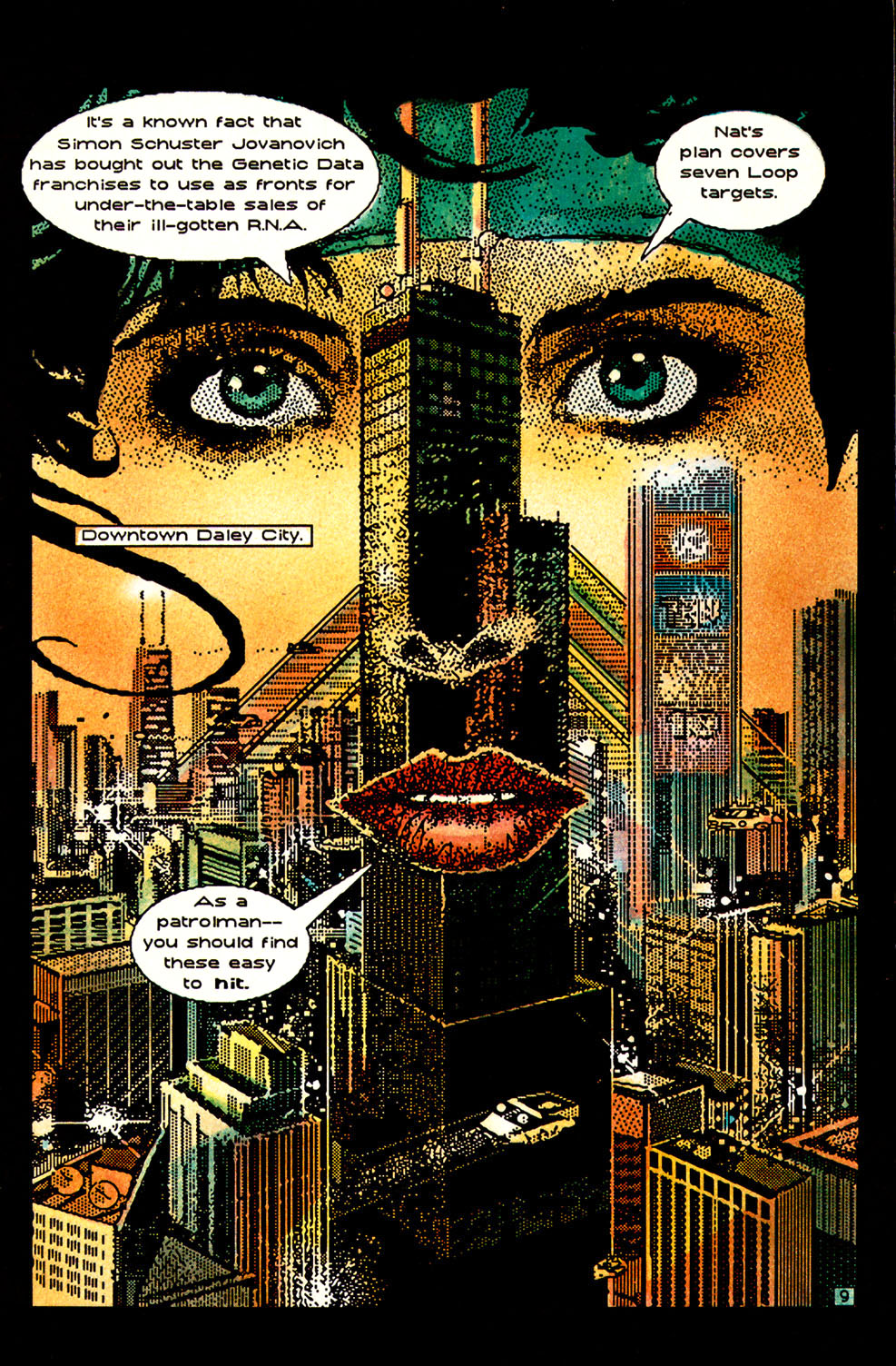

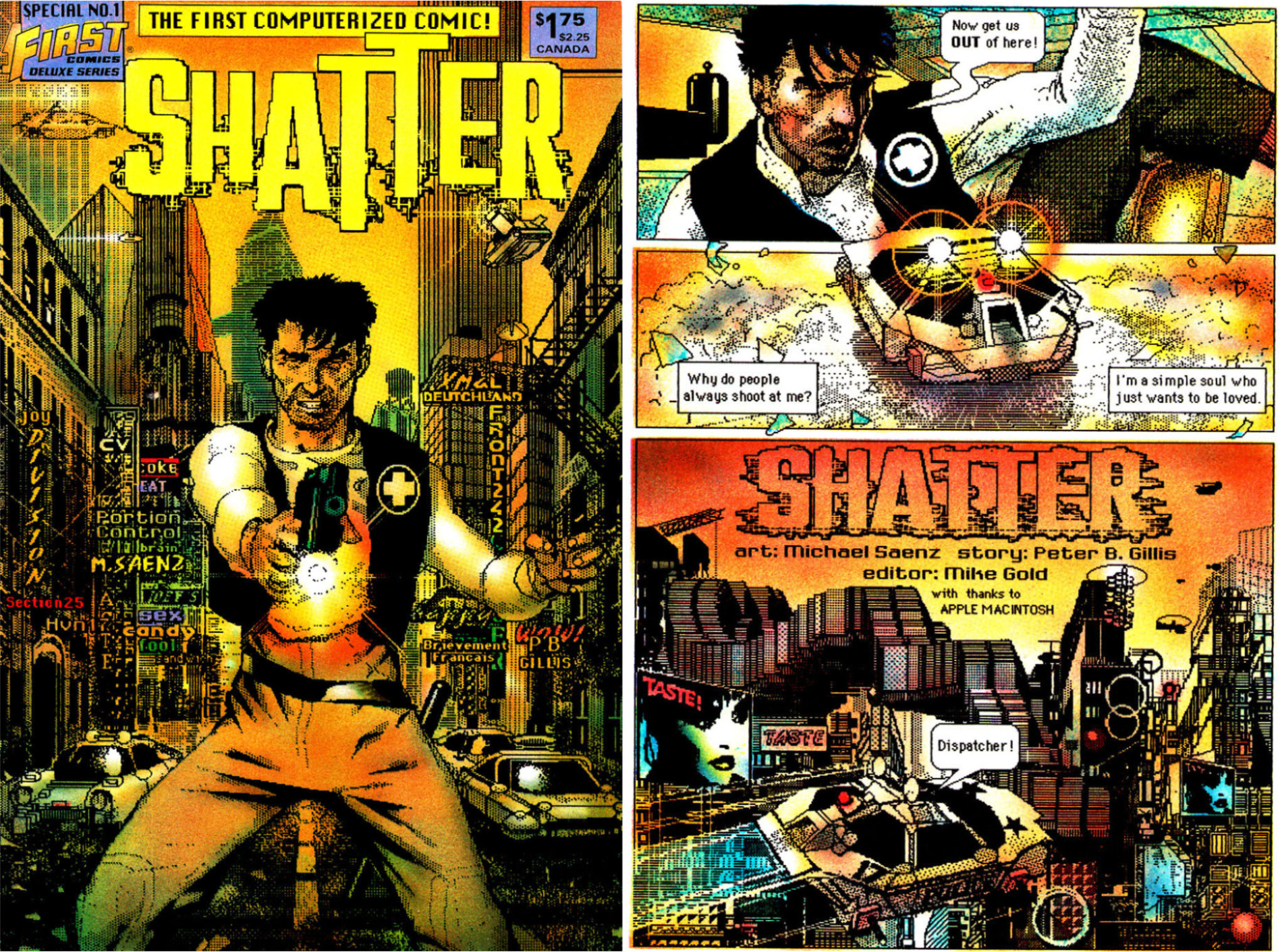

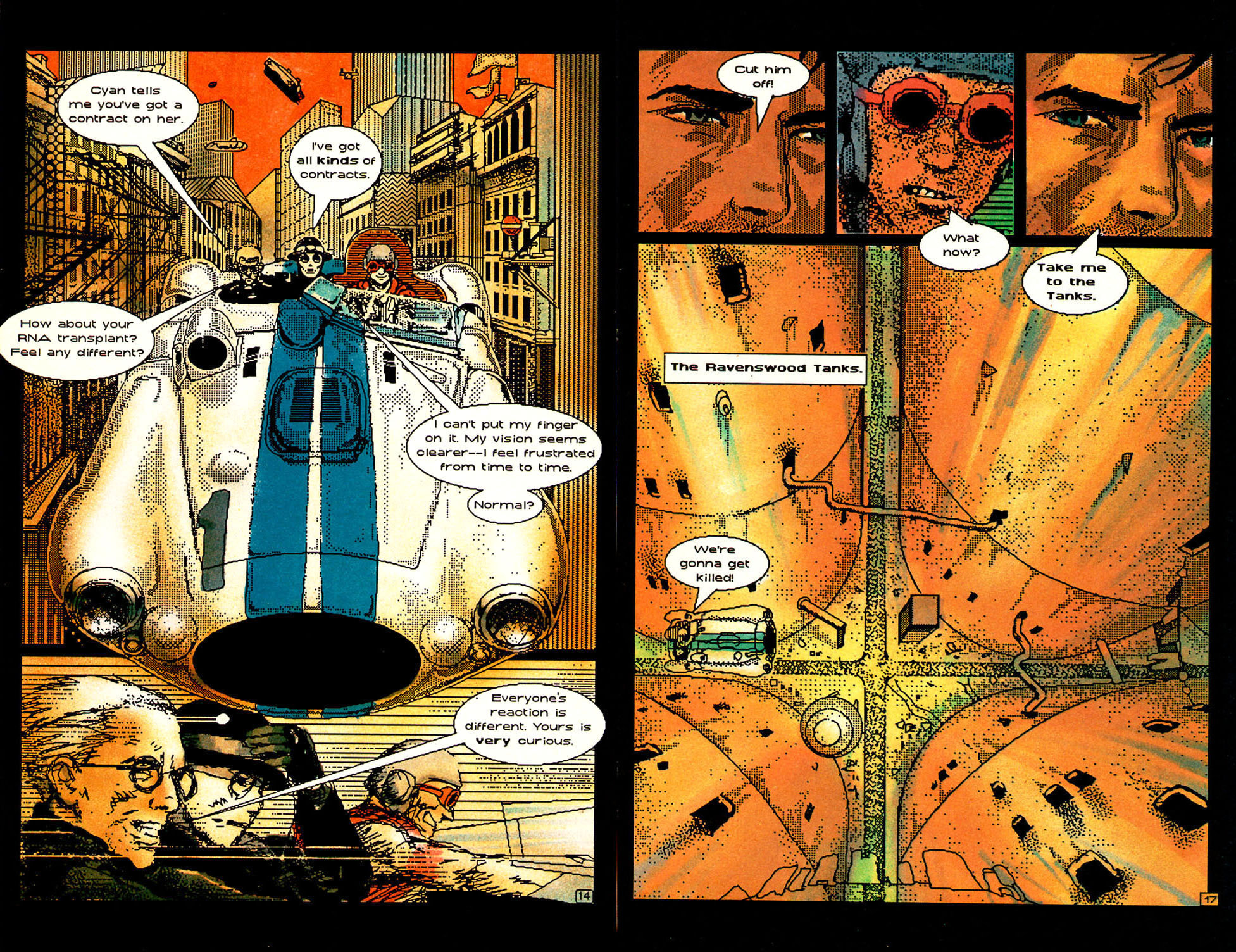

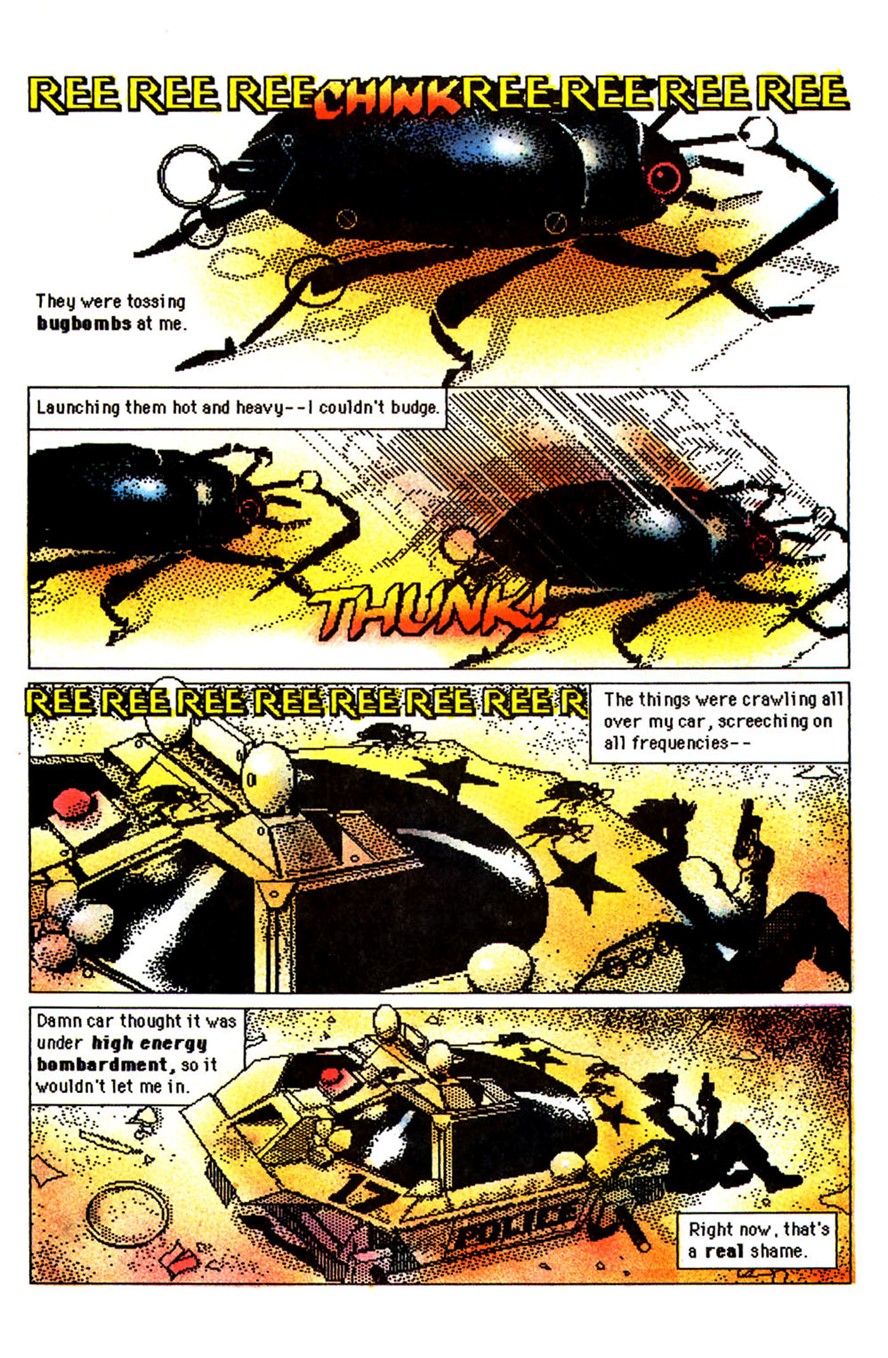

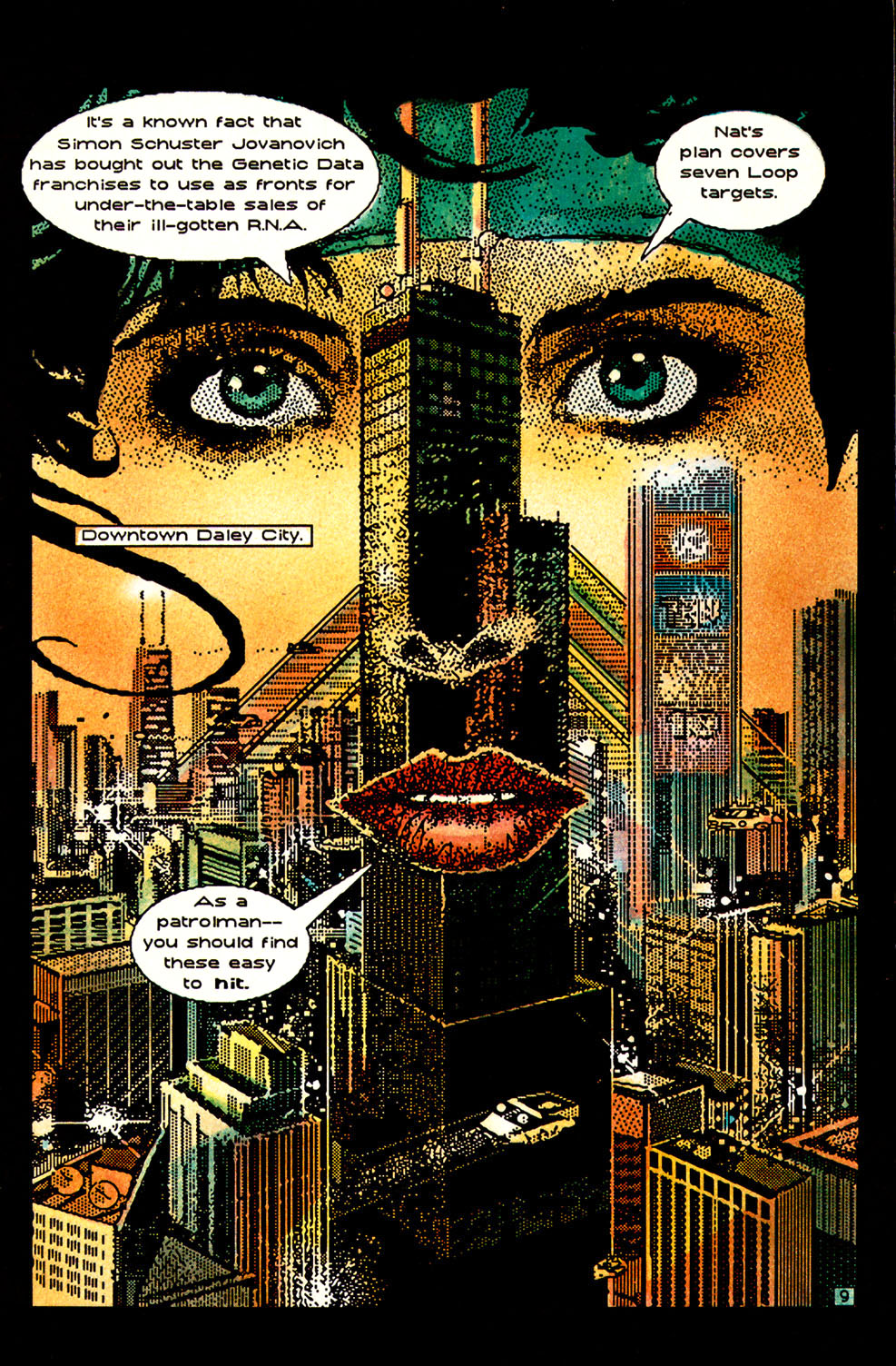

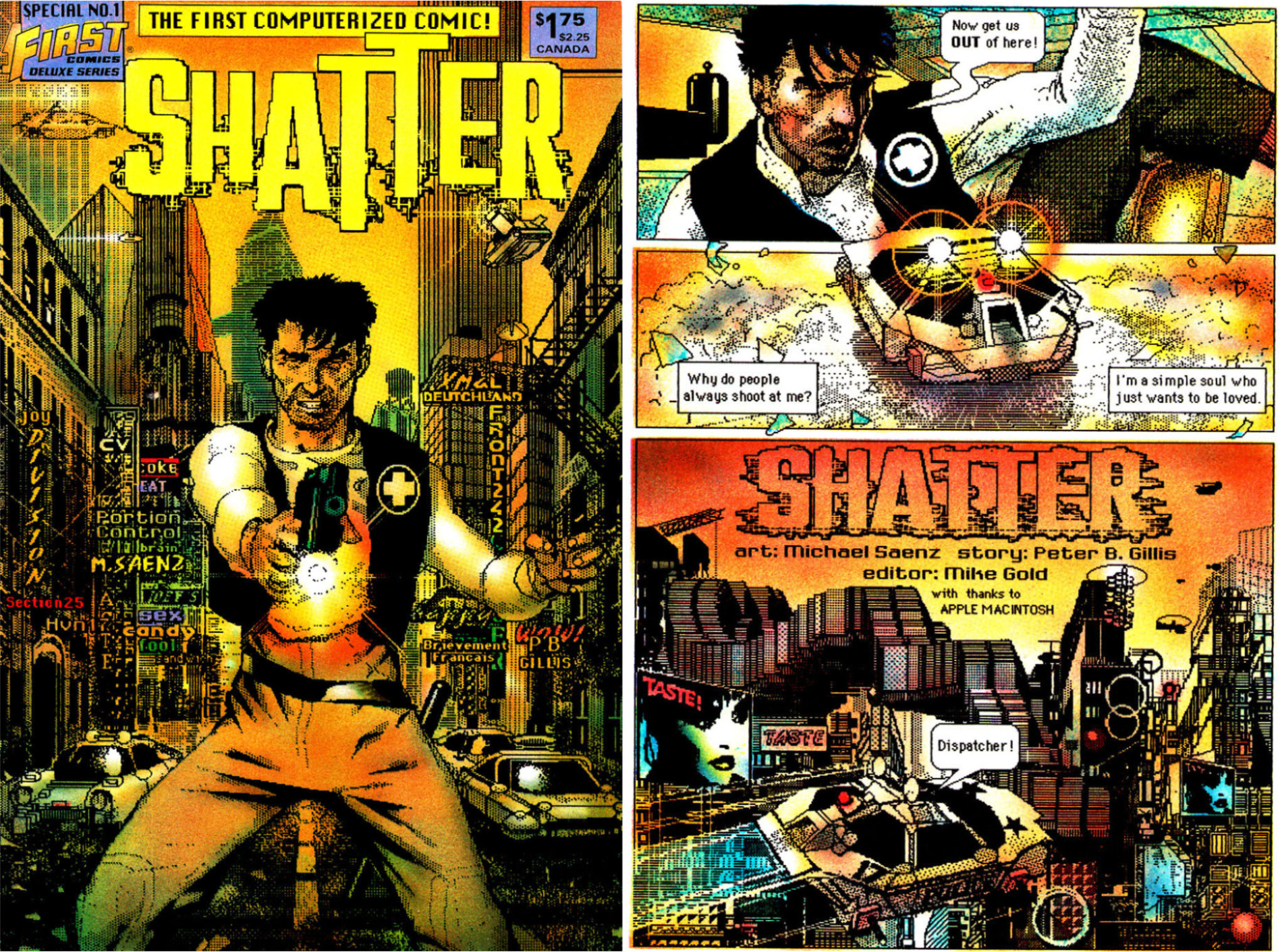

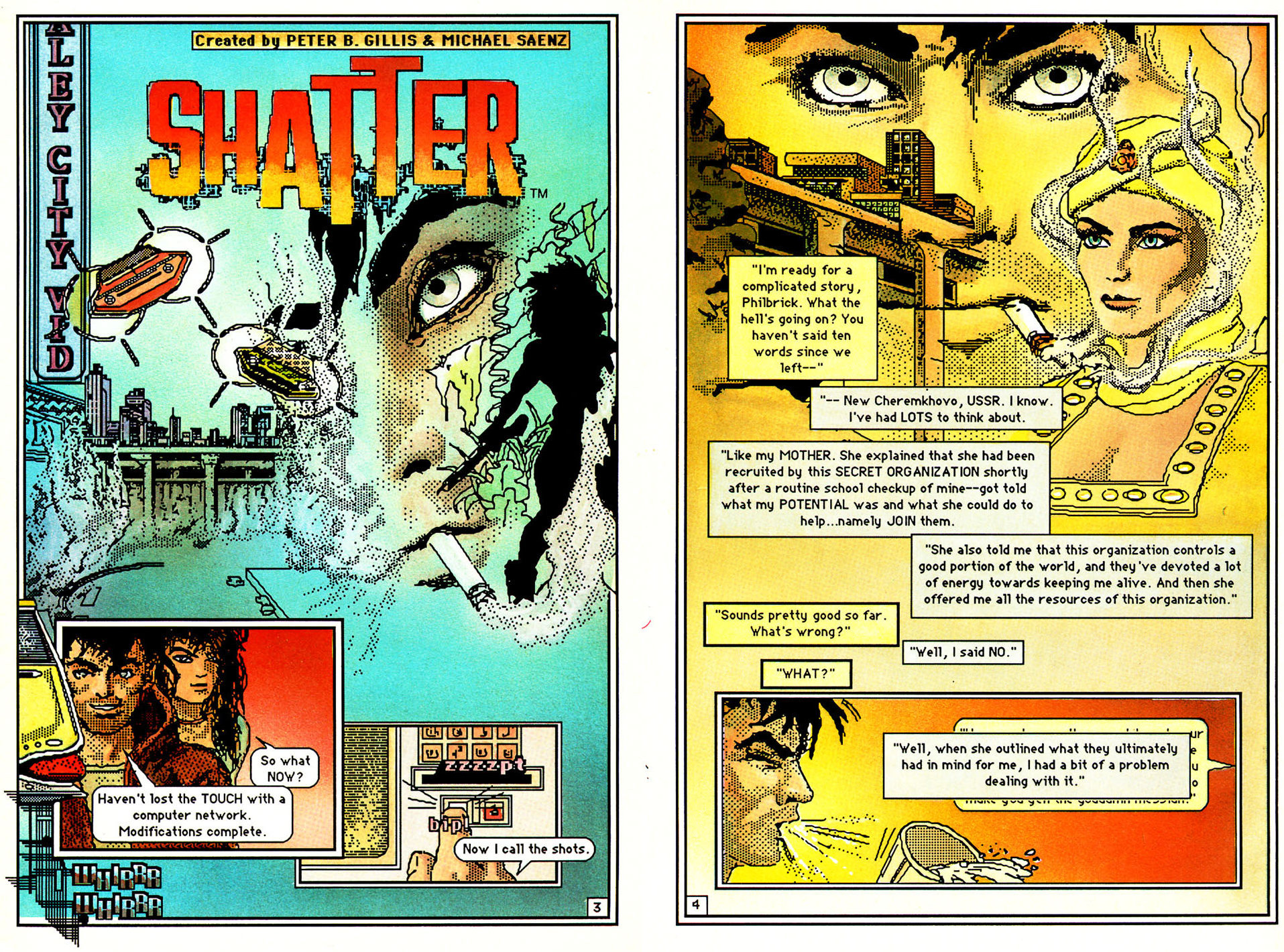

Figure 9: Splash page from Shatter #1 (art by Michael

Saenz).

What Is Shatter About?

First Comics Publishing's Shatter was created by artist

Mike Saenz and writer Peter B. Gillis. It is a self-described

tech-noir thriller, the story of the private eye Sadr al-Din

Morales, commonly referred to as Shatter. The story is

very much of its time. Much of it stands on the shoulders of

works such as Ridley Scott's 1982 film Bladerunner and

Gibson's novel Neuromancer. In its own campy way,

Shatter discusses concepts that are nowadays common and

perhaps even quaint, such as the dangers of technology in a

dystopian future and the distrust of corporations. In its own

way, the book eschews the main subject matter of mainstream

comic books by aspiring to be cyberpunk without explicitly

claiming to be it. Cyberpunk, we remember, is the grim and

gritty science fiction sub-genre. This "combination of lowlife

and high tech" (as described by Bruce Sterling in his preface to

William Gibson's Burning Chrome) features advanced

technology, such as global networks, brain-computer interfaces,

and artificial intelligence, all coexisting and competing with

the radical breakdown of social order, as only the early 1980s

could imagine.

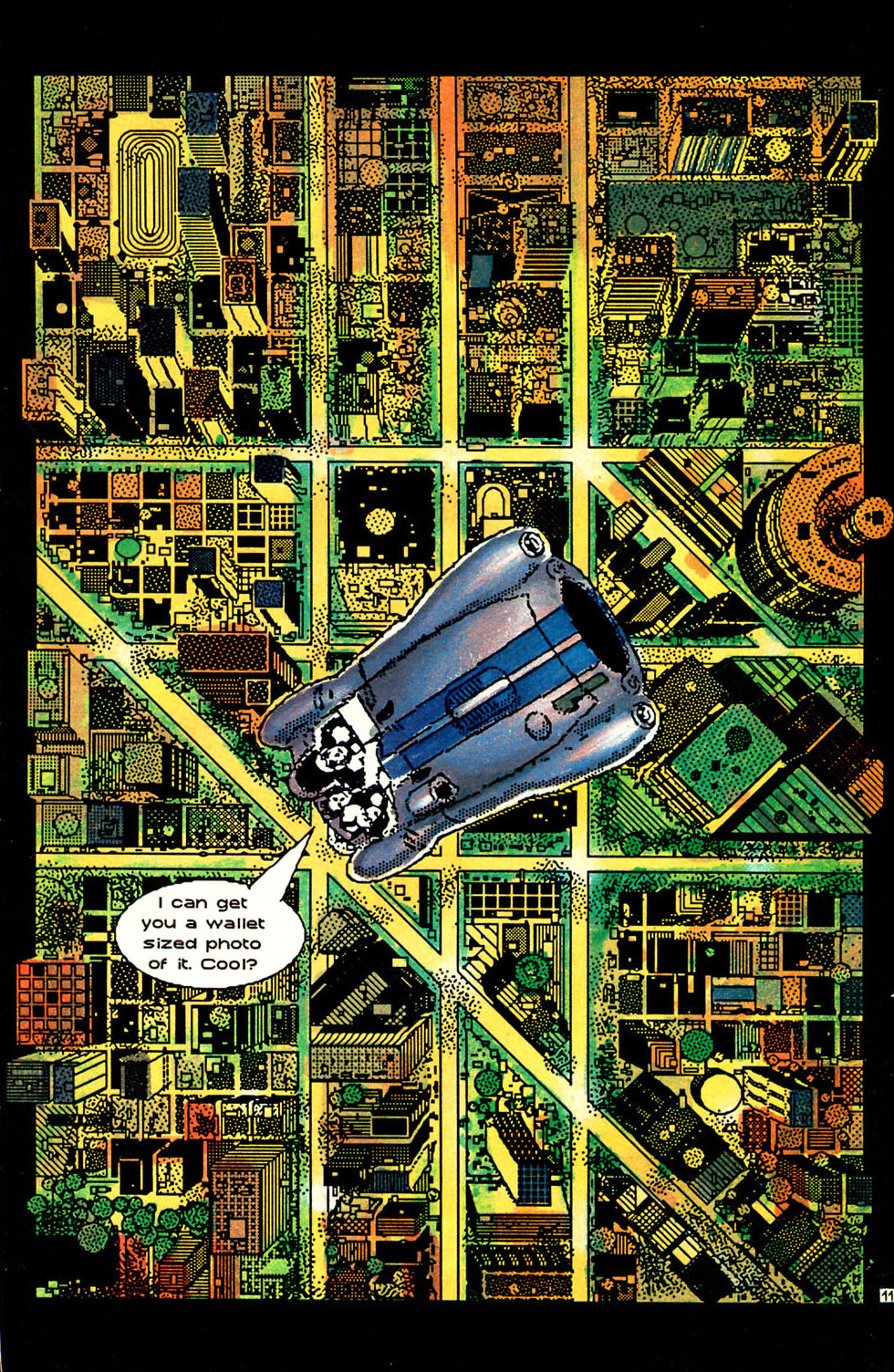

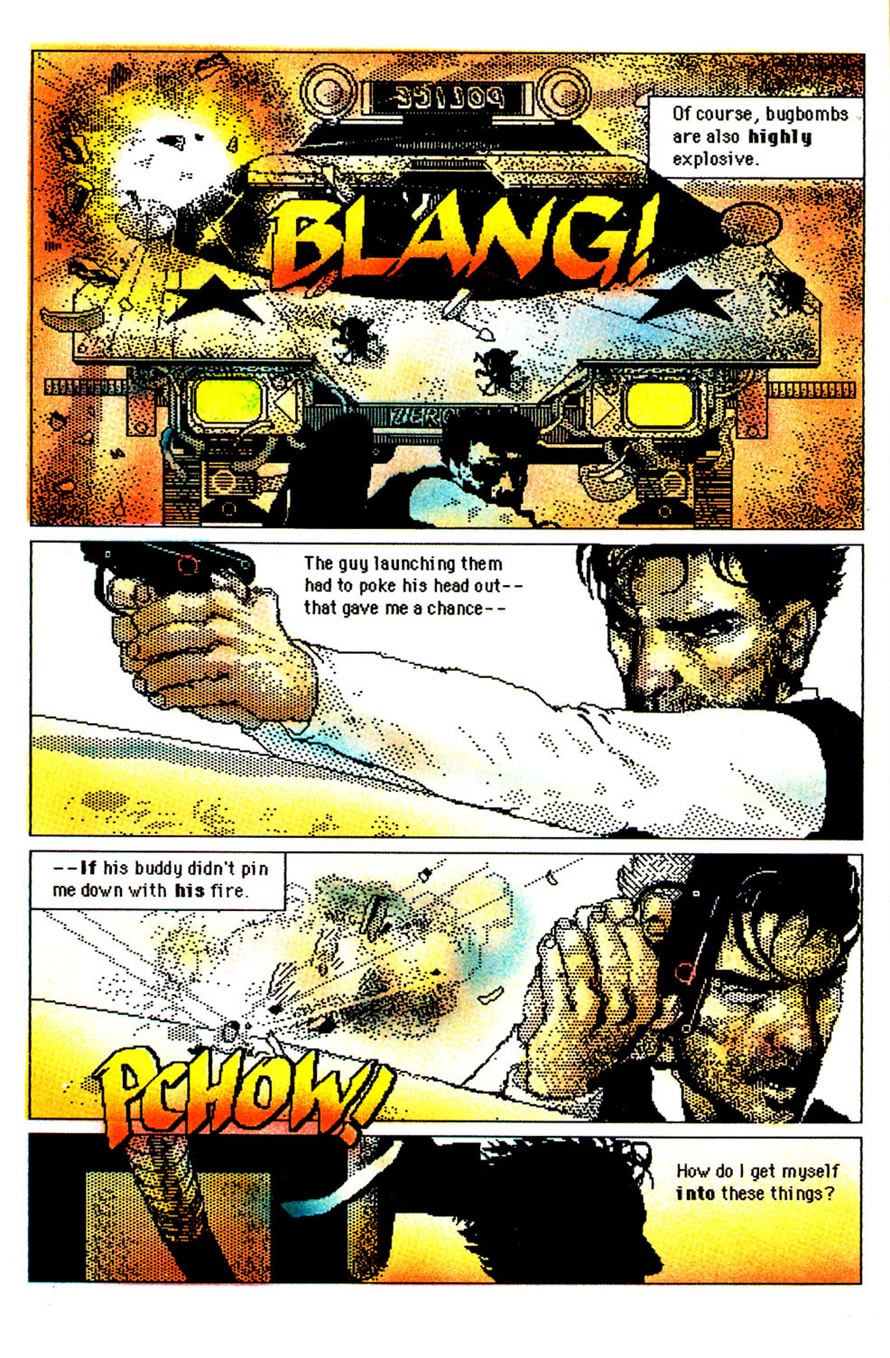

Figure 10: Splash page from Shatter #2, (art by Mike

Saenz).

The protagonist, Shatter, takes on the job of tracking

down a serial killer who killed the board members of a large

corporation. When he finds her, she reveals to him that the

corporation uses human RNA to transfer the skill sets of people

to others. Our hero finds himself involved with the underground

movement dedicated to stopping this practice. In a surprising

turn of events, Shatter finds out that he has "golden

brain" that keeps any RNA-induced talents indefinitely without

losing them, as everyone else does eventually.

Shatter occasionally veers toward the prophetic when it

depicts our protagonist bidding on a "gig" to take a case,

hinting at today's emerging "gig economy," as found on

fiverr.com and upwork.com. Other concepts sound unrealistic but

not completely out of the question, such as splicing talents

into a person's RNA to give them the special abilities of a

gifted artist, athlete, or businessman.

But the story is not what makes Shatter special. It is

the process of its creation.

Digital Storytelling

Finding a true "first" is never cut and dry, so calling

Shatter the first digitally produced comic might not be

completely true. If we dig deeply into the Bulletin Board System

(BBS) culture of the late 70s to early 80s, the precursor to the

web and the internet as we know it today, we will find users who

had distributed digitally produced comics as ASCII art,

semigraphics, or even as digitized captures of analog art. That

being said, Shatter deserves one commendation for being

"first": It definitely was the first commercially available

digitally produced comic book.

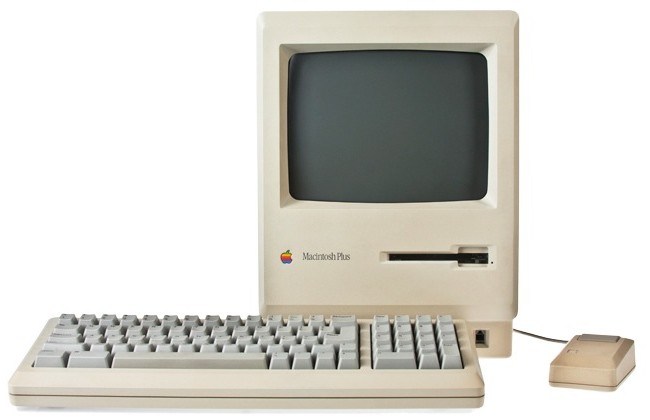

Figure 11: Apple Macintosh Plus(Image Source: shrineofapple.com)

In 1985 Shatter showed that the potential for

computer-assisted comic-book art was a reality. The art for

publication was drawn by hand on the computer as opposed to

later methods of scanning in inked pages for digital coloring.

Publisher First Comics Publishing had a potential hit on their

hands—a hit through the novelty of new technology.

Artist Mike Saenz started with a series of rough pencil sketches

for each page. These were reviewed by the editors of the comic.

When approved, Saenz drew the comic pages on a Macintosh Plus

with 1MB RAM using MacPaint and MacDraw. The pages were saved on

a disk drive with floppies holding a paltry 800 KB. The greatest

challenge was drawing on the nine-inch monochrome screen with a

resolution of 512 x 342 pixels. The screen was so small that the

artist could only see and work on a section of the current page

(by some accounts, two-thirds of the page). Saenz drew the pages using the standard Mac mouse; there

were no scanners available to capture analog art, and the

artists of Shatter only procured digitizer tablets at a

later time.

For the first issues, the artist printed the pages on an Apple

dot-matrix ImageWriter. In late 1985, when the regular series

launched, Apple donated a LaserWriter.

Quoting series editor Mike Gold in the editorial of

Shatter #1:

Better still, Apple came out with their LaserWriter, an

unbelievable printer that produces crisp, sharp printouts of

Mike's work. For graphics art reproduction, the difference

between the LaserWriter and traditional dot-matrix printers is

like the difference between glossy coffee-table art books and

paintings on cave walls. And better still, the folks up at Apple

gave us a LaserWriter. That sucker isn't

exactly cheap; it's nice to know you're appreciated. Thanks,

Apple!

The LaserWriter enabled Adobe PostScript font styles for

typesetting text and made illustration graphics smoother and

less pixelated because of the device's powerful interpolation.

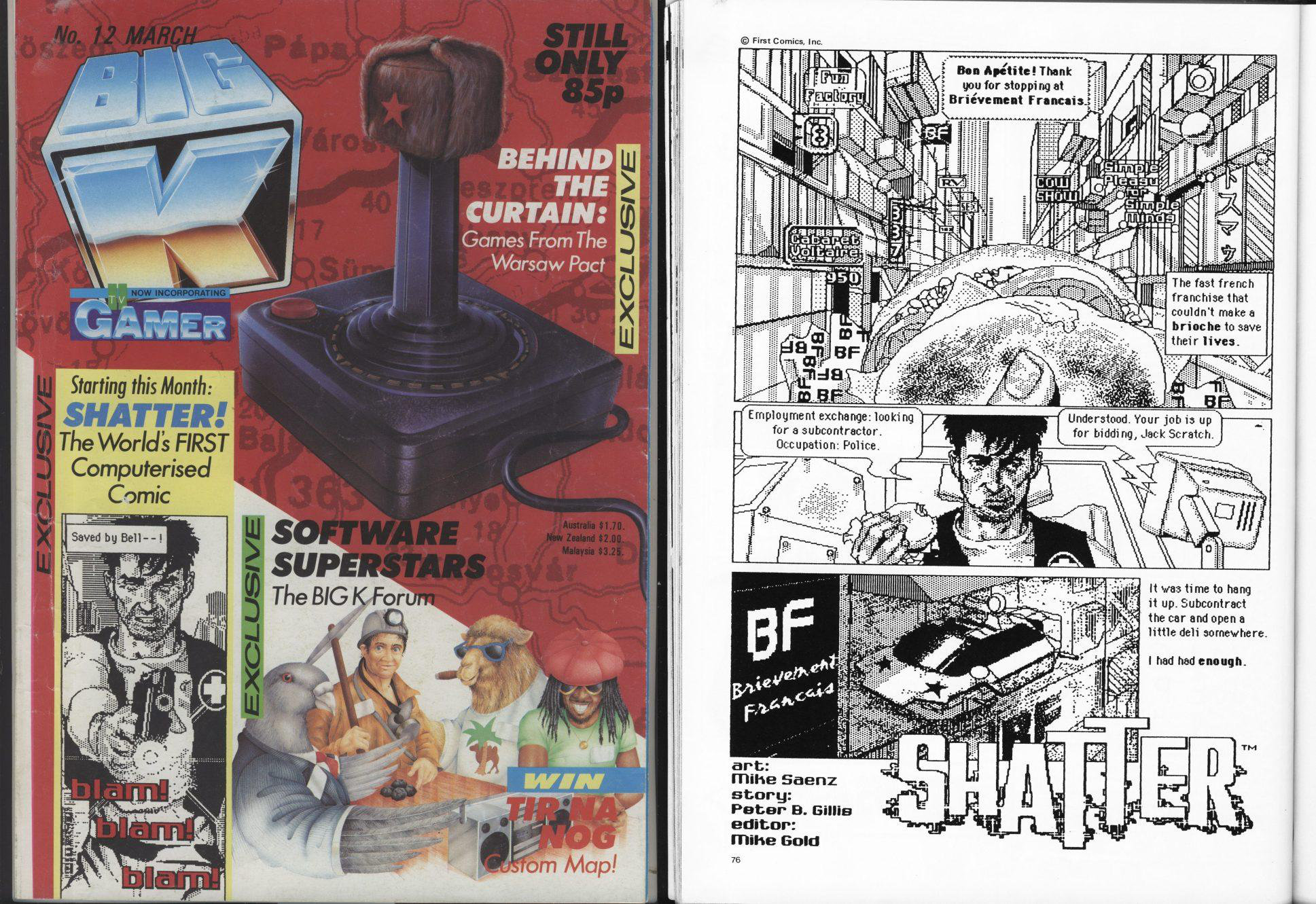

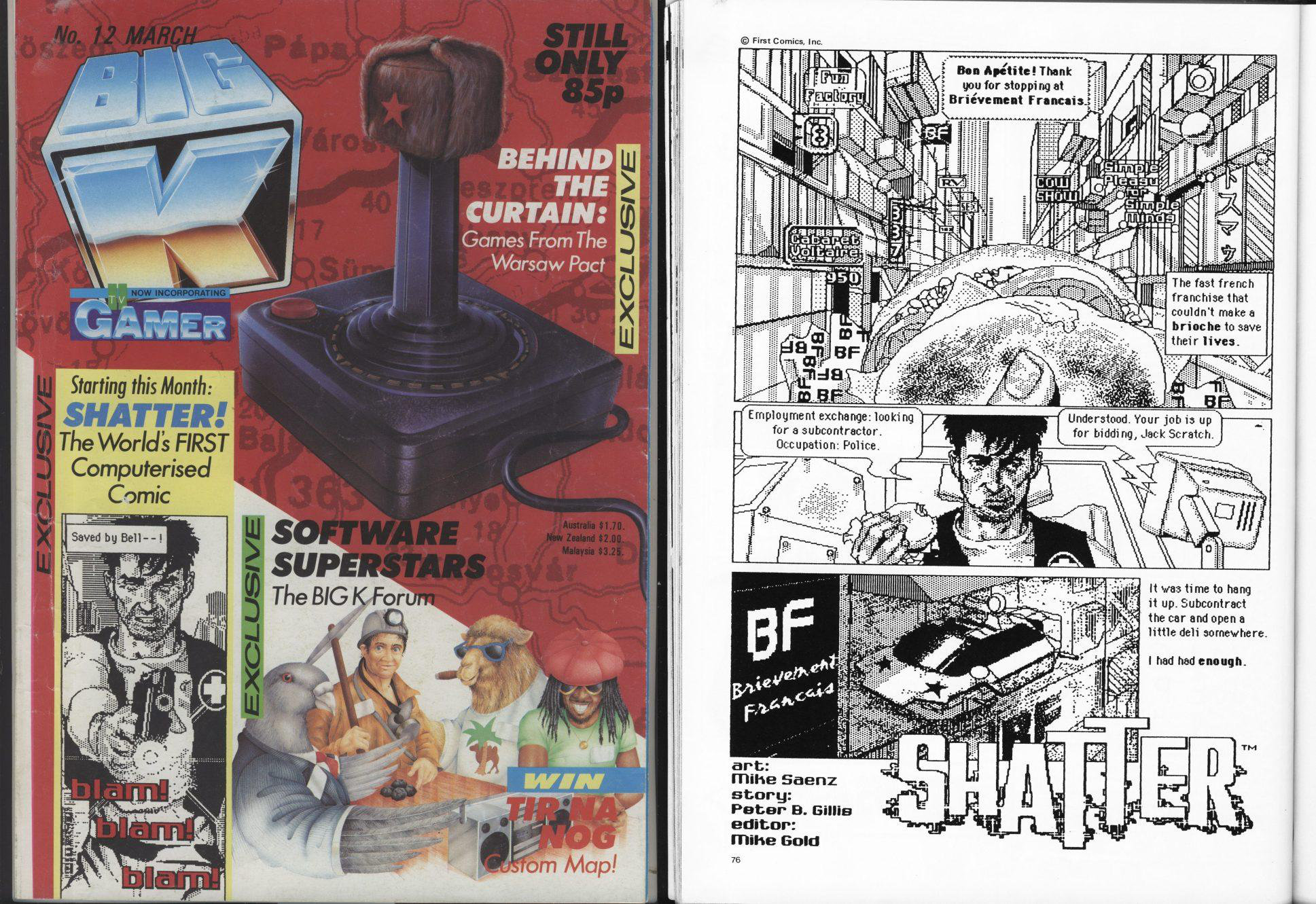

Figure 12: The first ever publication of Shatter in the

pages of Big K.

First Comics Publishing and the History of Shatter

The three people most closely identified with

Shatter are artist Mike Saenz, writer Peter B. Gillis

(both of whom created the series), and artist Charlie Athanas,

who joined the publication in issue #8.

Chicago-born artist Mike Saenz started work on

Shatter at the age of 26. The book was among his first

professional work and served as his breakthrough. After working

on Shatter, Saenz went on to produce digital comics for

Marvel and to work in software development.

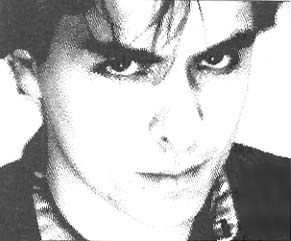

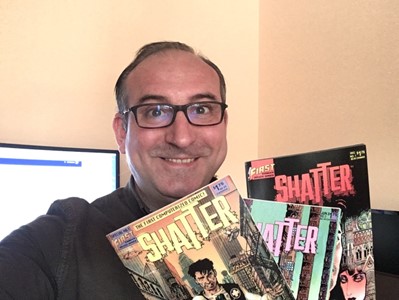

Figure 13: Mike Saenz in 1985 (source:

http://marvel.wikia.com/wiki/Mike_Saenz)

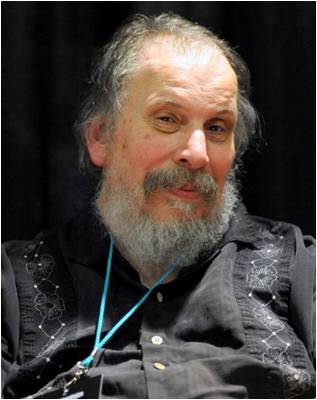

Peter B. Gillis was an established comics writer when he started

work on Shatter at the age of 32. He had freelanced for

Marvel Comics with his first published story in

Captain America. After numerous credits in Marvel's

second-tier comic books, Gillis went on to work as an editor for

the Florida-based publisher New Media Publishing until 1981. His

first work for First Comics Publishing was the science-fiction

series Warp until 1985. Then he joined the team of

Shatter.

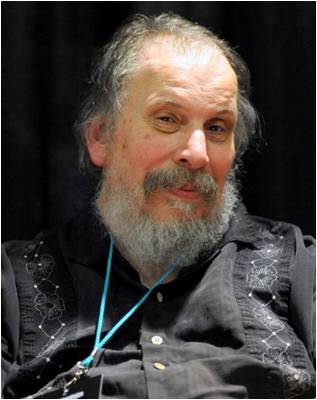

Figure 14: Peter B. Gillis in the 2010s (source:

http://comicbookdb.com/creator.php?ID=960)

In the early 1980s, publisher First Comics Publishing was one of

the few alternatives to the "big two": Marvel Comics (Spider-Man,

X-Men, Avengers) and DC Comics (Superman,

Batman, Wonder Woman).

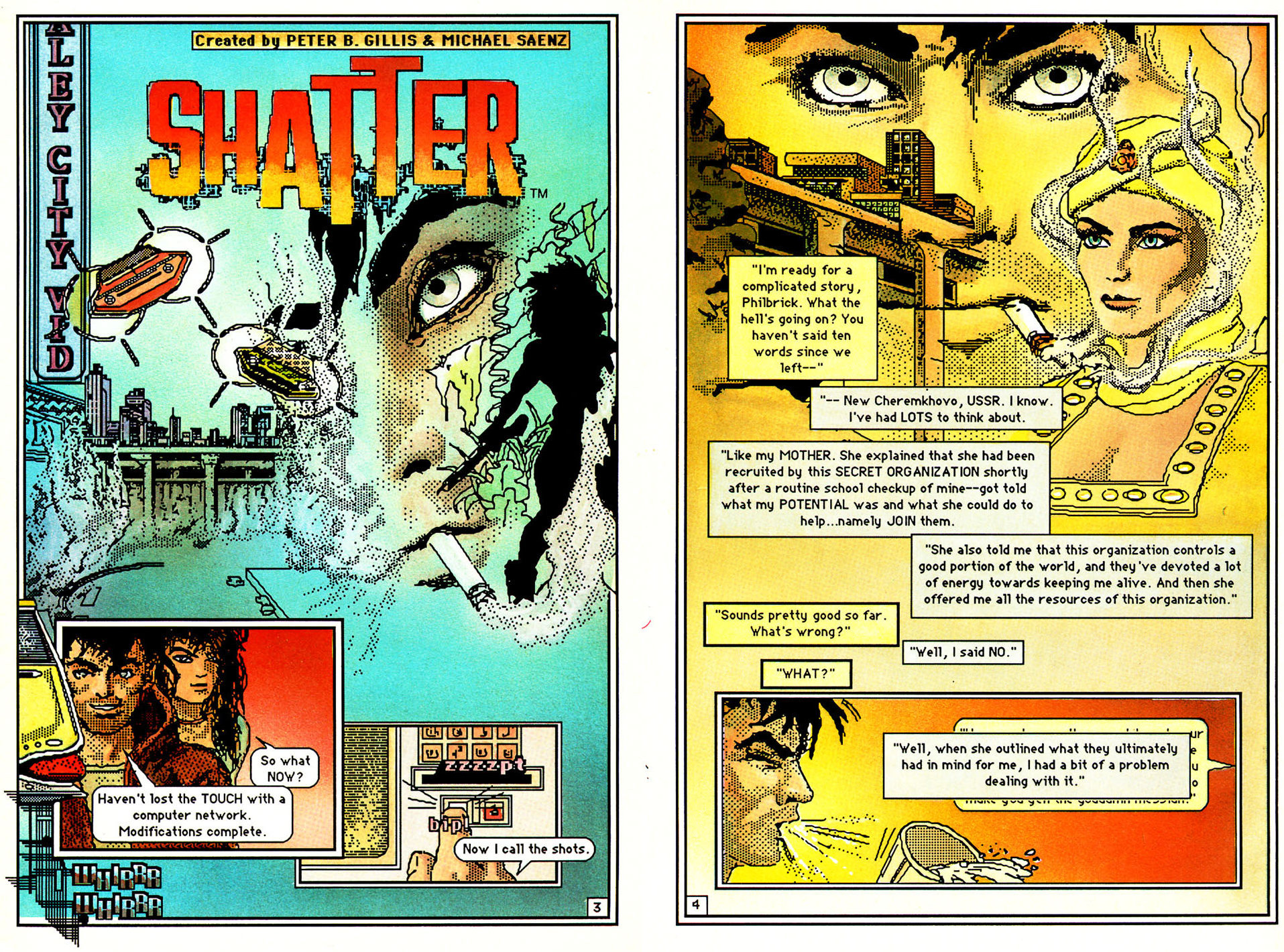

Shatter saw its first printing in the British computer

games magazine Big K, issue #12, its last issue before

it ceased publication. It was a four-page story printed in black

and white.

The series was touted as "the first computerized comic."

According to one report, Saenz and Gillis had offered the series

to Marvel Comics, who declined; only then was it picked up by

First Comics Publishing.

After its debut, Shatter went on to be published by

First Comics Publishing (Chicago) as a back-up feature to the

ongoing comic series Jon Sable. These eight-page

installments ran from issues #25 to #30 of the

Jon Sable series. The feature proved to be so popular

that publisher First Comics decided to release a

Shatter special issue with 28 original story pages by

Mike Saenz and Peter B. Gillis.

Figure 15: Shatter Special #1 cover (left) and interior

art (right), 1985.

It sold 100,000 copies in three days, breaking the existing

sales records for independent comic books. In 1985 a

high-selling issue of Marvel Comics's

The Uncanny X-Men sold 300,000 copies. By comparison,

sales of Shatter were very impressive for an

independent comics publisher.

First Comics commissioned an ongoing series. At this point,

writer Peter B. Gillis had moved on, so the artist Mike Saenz

started to not only draw the book but also provide the plot and

script.

The first issue of the ongoing Shatter series sold

60,000 copies. After releasing issue #2, Mike Saenz left his

creation to work on other projects. In 1988 he would go on to

produce the full-color digital graphic novel

Iron Man: Crash for Marvel Comics and work on the comic

creation app ComicWorks before being bought out by software

maker Macromedia.

Audience Reactions

This paper was written in 2018. Now, more than 30 years later,

it is difficult to assess what the original audience reaction

was at the time of publication. The few remaining reviews show

very positive feedback lauding the use of the Macintosh. In

hindsight, much of the praise is directed towards the promised

potential of digital art and not always the results on display

at the time.

In the series' letters pages, readers criticized the story for

being a derivative of Blade Runner. In issue #2, one

reader writes:

"The only thing bad about it is the story. It does not make much

sense and the whole thing is terrible."

While the digital art did find a lot of praise ("The graphics

inside are excellent" from the letters column in issue #2), it

was not universally praised, as can be seen in this letter from

the same issue:

"The graphics in Shatter are likely to be more of a

turn off to potential computer comic connoisseurs due to their

primitive quality and unimaginative execution."

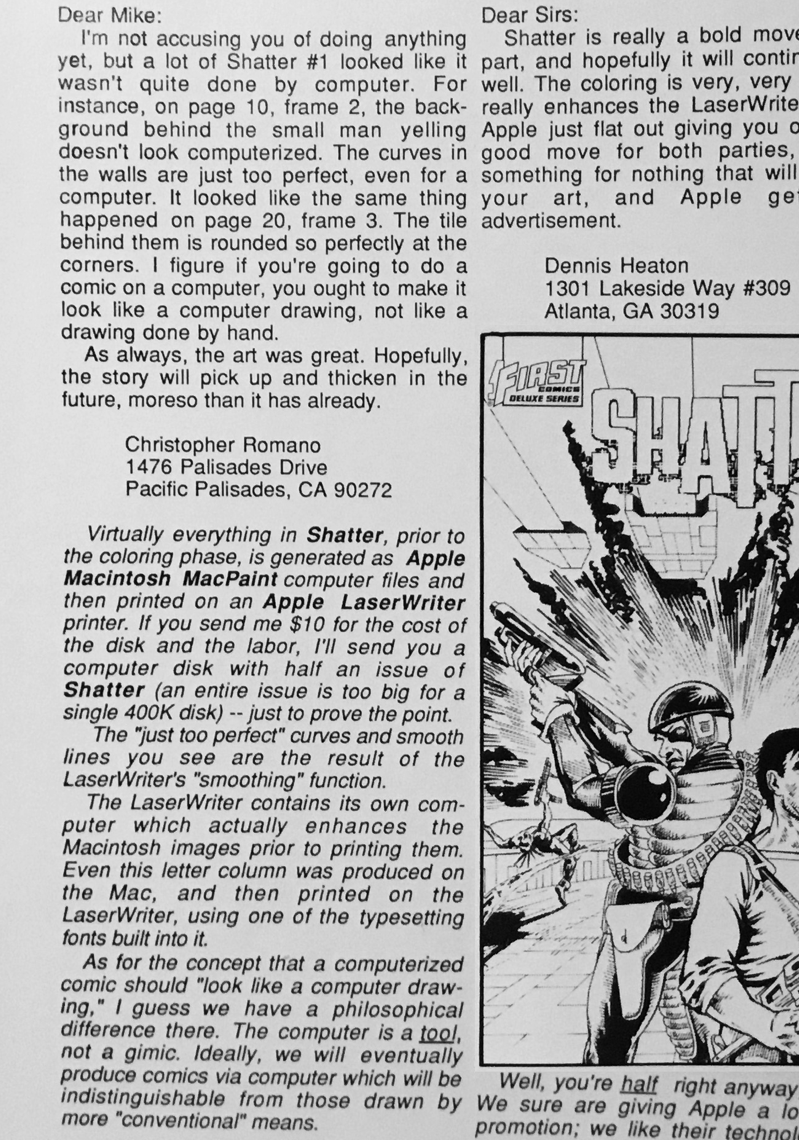

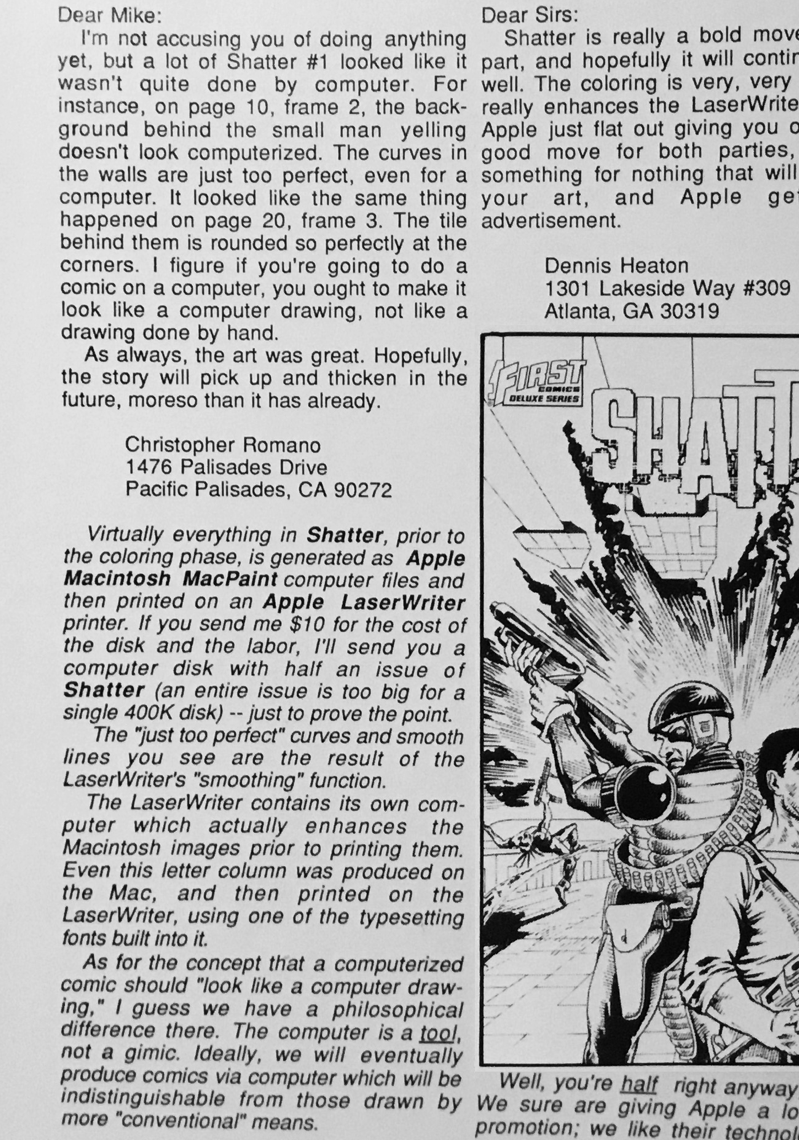

The oddest reactions still available in their original form are

from the letters pages of the series. First Comics Publishing

advertised the digital nature of the series and went to great

lengths to explain the process in its editorial pages.

Nevertheless, in issue #3, a reader writes that they doubt that

the art was, in fact, produced on a computer:

I'm not accusing you of doing anything yet, but a lot of

Shatter #1 looked like it wasn't quite done by computer

... The curves in the walls are just too perfect, even for a

computer ... I figure if you're going to do a comic on a

computer, you ought to make it look like a computer drawing, not

like a drawing done by hand.

The editor responded that for a small fee they would be happy to

send a disk to the reader with the original artwork in its

digital form as proof.

Figure 16: Readers' baffling reactions in the letters page.

After moving on to DC Comics, Mike Gold, the original editor of

Shatter, reminisced about the series in the

introduction of DC's own digital comic effort

Batman: Digital Justice in 1990 (emphasis provided by

the writer of this paper):

At that time, I was the editor of a midwest comic book company

when a couple of old friends, Peter Gillis and Mike Saenz,

showed me rough printouts of a story that was produced on a 128

K Apple Macintosh computer, using but one disk drive. The

artwork was chunky and brittle: it looked like

some amphetamine addict had been given a box of a zip-a-tone

that suffered from a glandular disease.

But the look was totally unique to comics. Within several

months, we refined the look and the resulting effort

Shatter was one of the best-selling comics of the year.

It completely astonished the folks over at Apple Computer, Inc.,

who never perceived such a use for their hardware.

Tumultuous Changes

Ultimately, Shatter would run for 14 issues from 1985

to 1988, but in 1986, after Mike Saenz left, First Comics

Publishing did not want its successful series to suffer delay.

Not to leave the series without a writer and an artist, Steven

Grant jumped in to fill the writer's role for issues #3 and #4

while Steve Erwin and Bob Dienenthal took over the art chores

for issues #3 to #7.

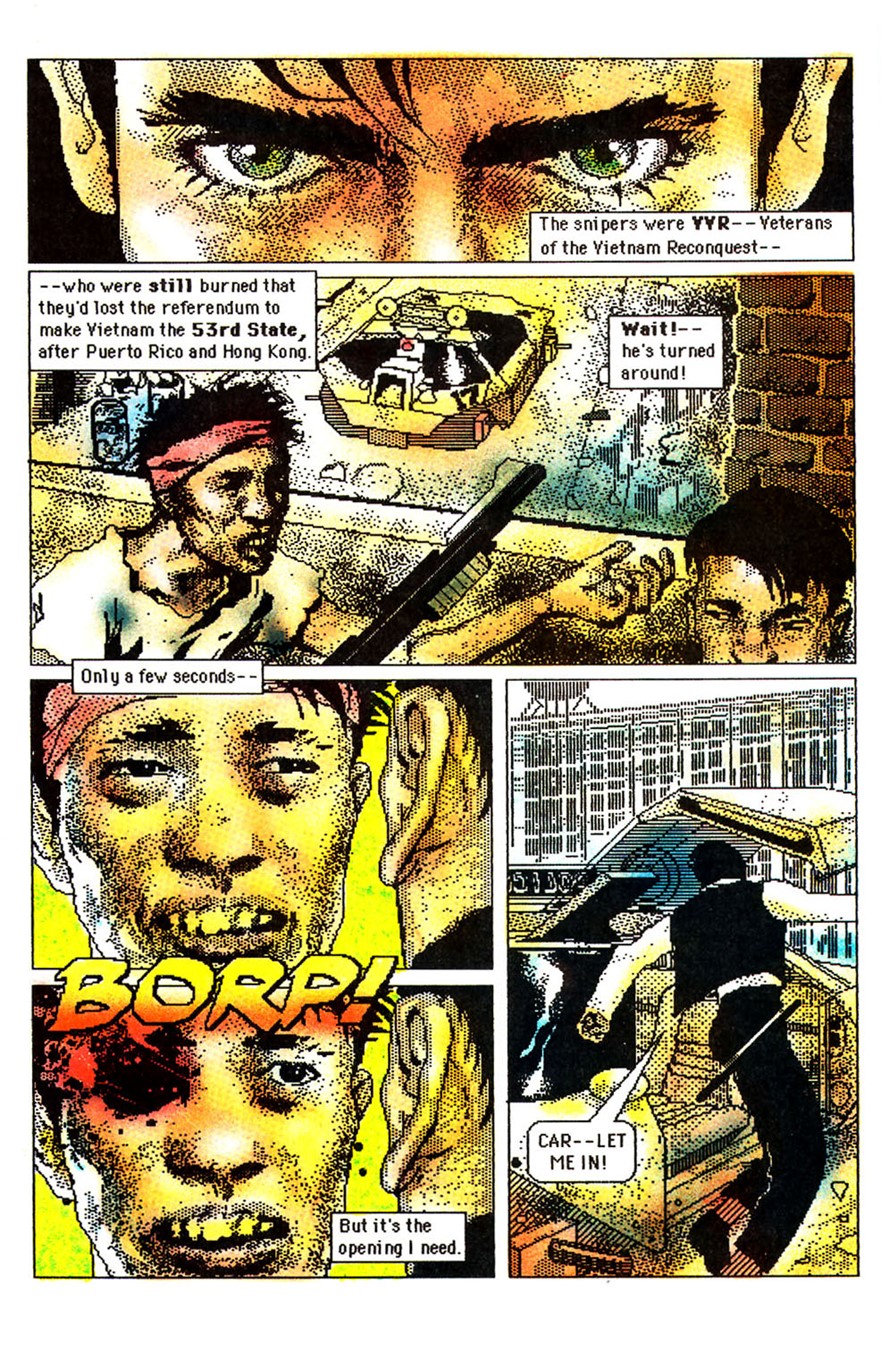

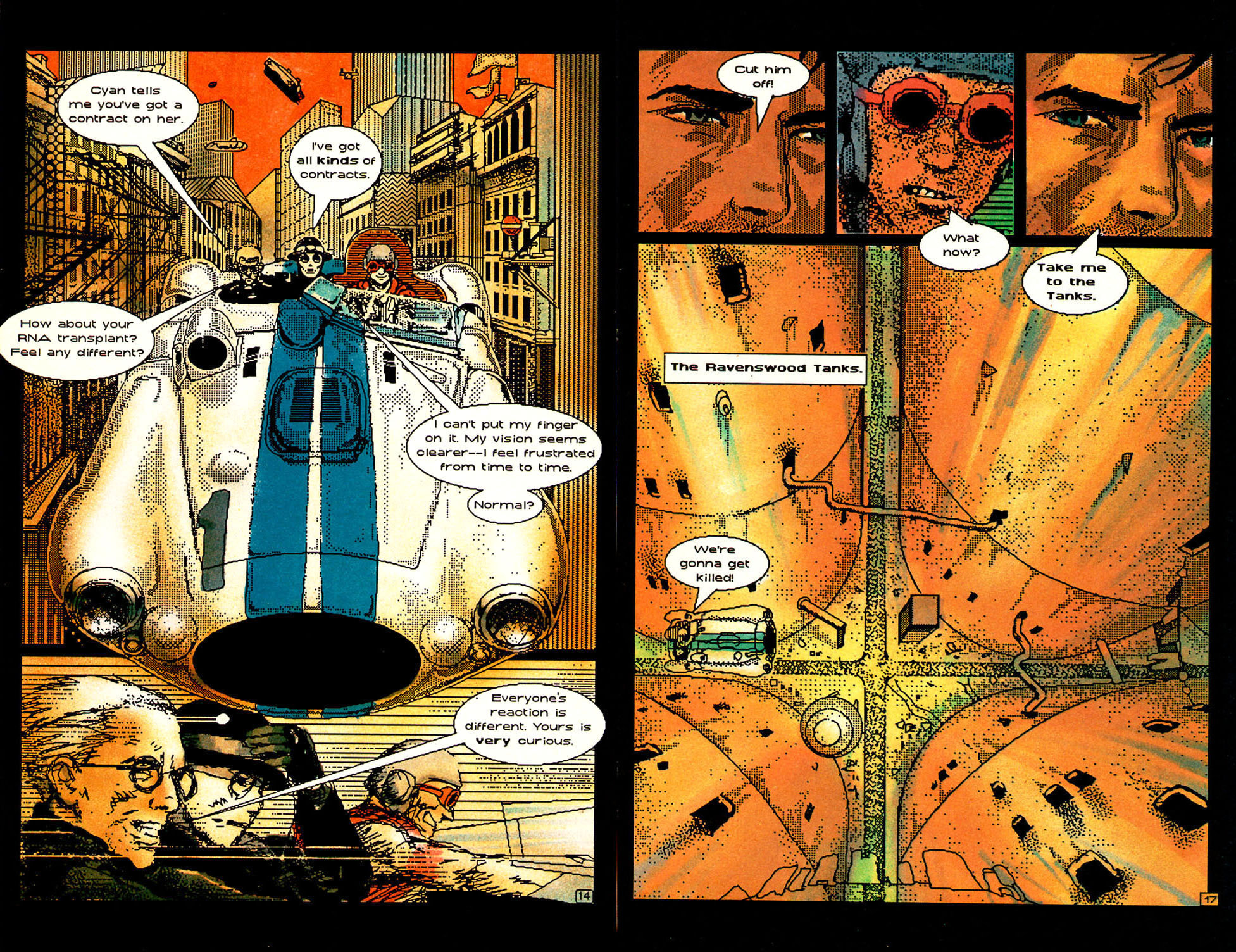

Figure 17: Interior story page from Shatter #2 (art by

Mike Saenz).

The art in these issues was workable but no longer special

because the artists penciled and inked traditionally and had

their pages scanned into the Macintosh to be lettered in

MacPaint. This deprived Shatter of its special look.

The art degraded to standard comic book art, albeit strongly

pixelated to suggest that computers remained a vital part of the

production process.

At least in issue #5, original writer Peter B. Gillis returned

to the fold to give the story focus and the dialog edge. But

Shatter would still need another couple of issues

before it could hit its stride with a new artist coming on

board.

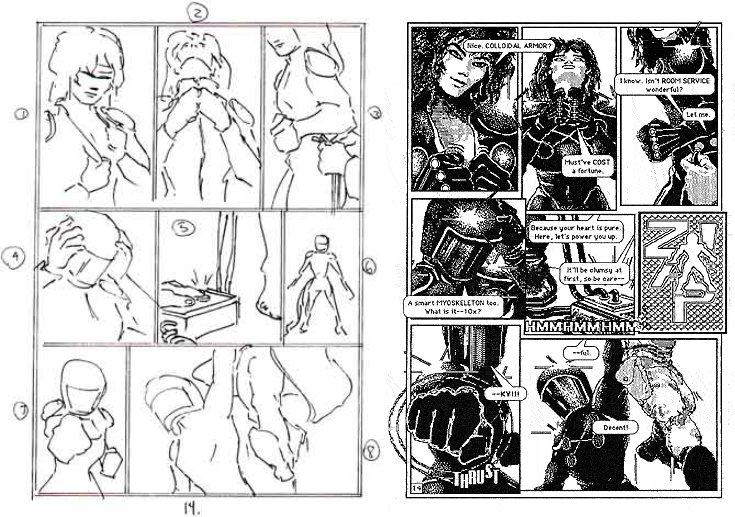

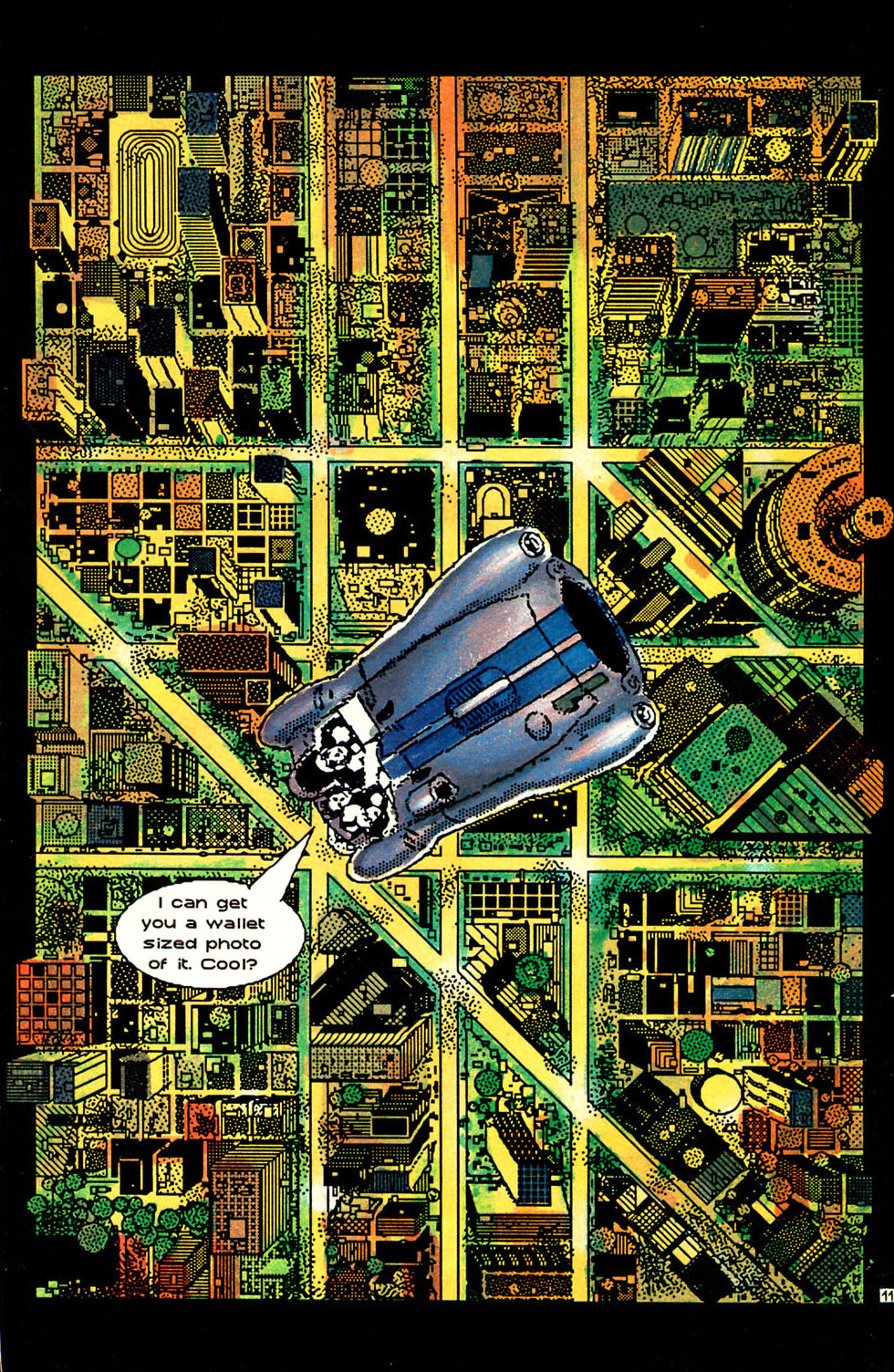

Charlie Athanas to the Rescue

The departure of Mike Saenz left Shatter without its

main selling point: art drawn directly on a computer. The book

needed to return to its unique art style. It needed a new artist

who was capable of producing the artwork on a Macintosh. Enter

Charlie Athanas. This young artist from Illinois joined the team just in time

to continue the storyline Peter B. Gillis started.

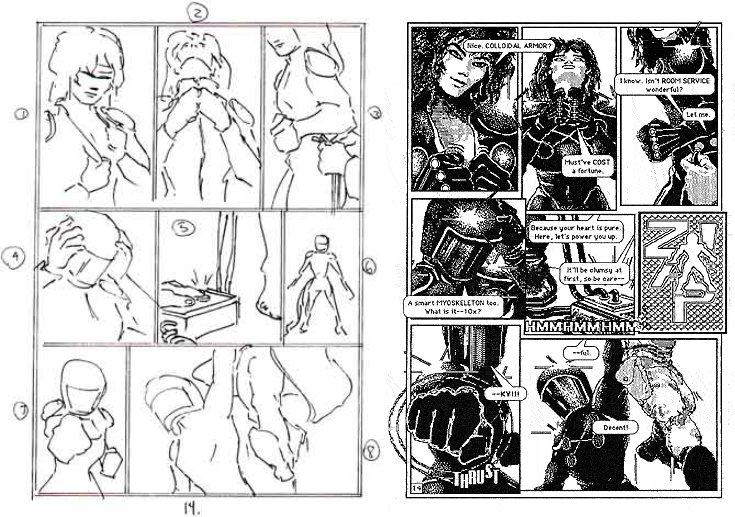

On his website, Athanas describes the process:

Artwork created from layout to the black and white 'camera

ready' art before color was added in the traditional method. I

produced this art on a MacPlus with 1 MB of RAM and an 800 K

floppy drive. Only about two-thirds of a full page was visible

to work on unless you switched to thumbnail mode to see the

entire page on a drastically reduced scale. About half the

issues were drawn with the standard Mac mouse until a small

drawing tablet became commercially available.

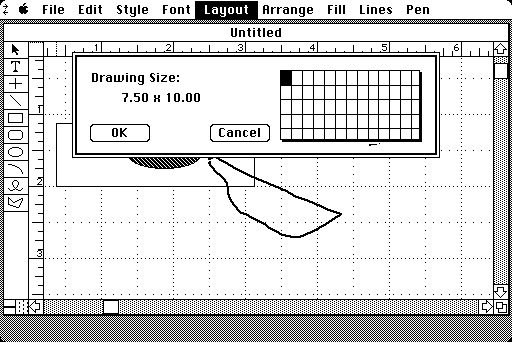

Figure 18: Athanas's rough thumbnail sketch of a page (left) and

the final monochrome artwork (right).

Athanas re-established drawing directly on the Macintosh Plus

with the computer mouse. To speed up publication efficiency,

Athanas drafted rough pencil sketches in order to sketch out

layout design, speed up the writing of the script, and go

through editorial review.

Figure 19: Charlie Athanas in the 2010s (source:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/charlieathanas/)

Without scanners at his disposal, Athanas manually redrew the

rough sketches directly on this Mac. Now that the series was

back to computer-drawn artwork, the pages had a much cleaner art

style. Athanas not only used MacPaint but also FullPaint by Ann

Arbor Softworks.

Figure 20: Interior story pages from Shatter #9 (art by

Charlie Athanas).

Shatter was saved for the time being. Sales stabilized

with the new creative team. But alas, technology progressed at a

breakneck pace in the mid to late 80s. The home-computer

revolution had started to sweep computers into every American

household. A comic series about a dystopian future no longer

captured its readers' imaginations. With issue #12, Peter B.

Gillis left as a writer to be succeeded by Jay Case. First

Comics Publishing met with financial difficulties, and the

series' novelty of new technology wore off. Sales started to

slip, and by 1988 they had dropped sufficiently to make the

publication no longer viable. First Comics Publishing allowed

the creators to complete their story but no longer start a new

one. Shatter was cancelled with issue #14.

Thus ended the first sustained experiment in commercial

digital-art production after three tumultuous years. By then,

editor Mike Gold had left for DC Comics, leaving editor Rick

Oliver to write the last words for the series in the letters

page of Shatter #14 (cover date April 1988):

When Shatter first appeared, it was produced solely

with the software that came packaged with the Macintosh; Apple's

own MacPaint. More recently, we have also incorporated MacDraw,

Word, Switcher, MacBillboard, and FullPaint. This letters column

and the First Notes page were produced with Word and XPress, an

electronic page make-up program.

There are more new graphics programs available every day, each

more sophisticated than the last, and there's no telling where

it will all lead.

But for now, Shatter has served its purpose, and it's

time to move on. Thanks to all our loyal readers who stuck it

out through both the great and the not-so-great issues. Thanks

to Peter Gillis and Mike Saenz for starting the ball rolling,

Steve Erwin and Bob Dienethal for keeping it going and finally,

let's give a big hand for Charlie Athanas for revitalizing the

book for a classy finish.

The technology might not yet have been advanced enough, but

Shatter proved one thing to the comic book industry:

comics could be produced digitally, and dots by any other name

could still be art.

III. The Production Process

To destroy is always the first step in any creation.

- E. E. Cummings

For the purposes of this paper, it is of great interest to

compare the process used to create Shatter with the

process used most commonly in American comics of the 1980s and

then juxtapose that with the process used nowadays (2018). This

will show how much Shatter deviated from its

contemporaries and allow us to investigate how much of its

production process can be found in today's comic books.

The Typical Process in the 1980s

The writer of the comic typed the story and the script on his

typewriter and sent it to the editor for review.

Once approved, this physical script went to the penciller, who

sketched the rough layout scribbles of the 22 individual pages.

These were much smaller than the original artwork or the printed

page and served for design purposes. Then the penciller drew the

actual pages (usually at double the size of the printed page)

with the figures, the props, and the background scenery or

locations.

In some cases, the penciled pages were returned to the writer

who then provided the script for the captions, dialog, and

thought balloons. In other cases, the script already had all the

captions and dialog when the penciller received it.

In the next stage, the letterer drew the caption boxes, speech

bubbles, and thought balloons to then place the letters in them.

As soon as the penciled and lettered pages were completed, they

were sent to the inker. They redrew the penciller's art by

tracing the lines—providing them with weight, cleaning them up,

and giving the solids some texture. The inker made sure that

objects in the distance were drawn with a faint line and closer

objects or characters were drawn with the full weight they

needed to tell the story.

Finally, the colorist applied colors and tones to the artwork by

hand.

The pages of the comic book are then photographed for print and

reduced to the desired size.

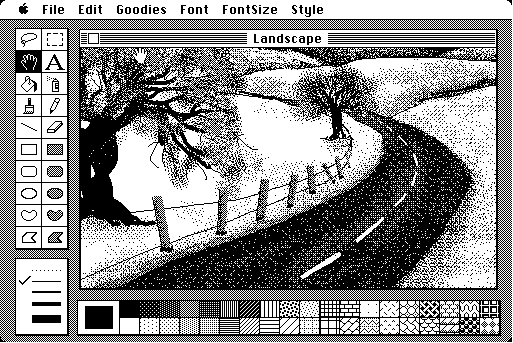

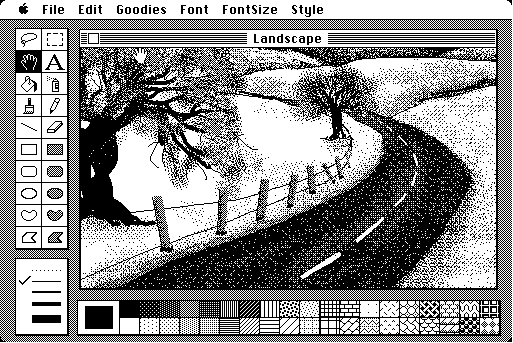

Figure 21: MacPaint on a monochrome Macintosh (ca. 1984).

The Process used for Shatter

The digital workflow of Shatter also starts with the

script. But as described by Mike Gold, the series' editor, in

the editorial of Shatter Special #1, "... Peter would

dialogue Mike's art on an Apple III, but it would be lettered on

the Mac."

In Shatter #3, Editor Mike Gold continued to describe

the process: "Virtually everything in Shatter, prior to

the coloring phase, is generated as Apple Macintosh MacPaint

computer files and then printed on an Apple Laserwriter."

And further in the editorial of Shatter Special #1:

Together with First Comics' production manager Alex Said and

editorial coordinator Rick Oliver, we agreed that every aspect

of Shatter would be performed on the Mac - the art, the

lettering, the logo, the advertising, even this editorial.

Everything but the color. We could create the color on the Mac

(and we could come up with some interesting effects by creating

a wider range of tones) but it would take far too much time.

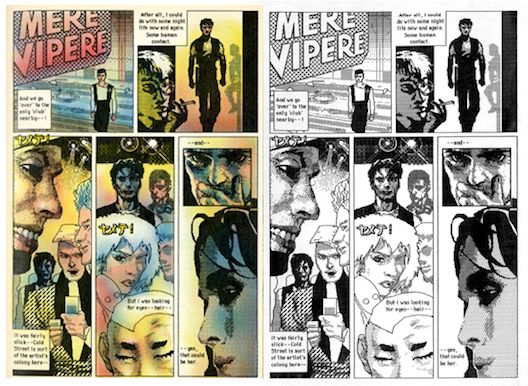

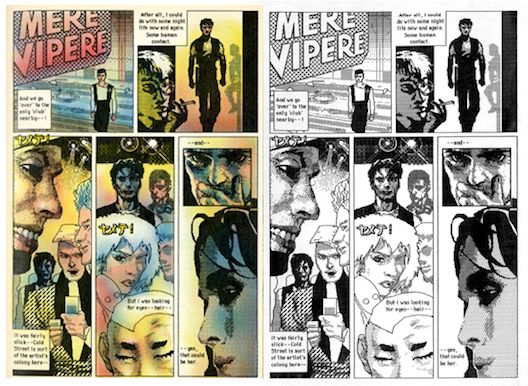

Figure 22: Interior story art from Shatter Special #1,

colored (left) and before coloring (right).

So, the process used for Shatter saved on transcribing

the script and on producing the pencils to be inked because the

artwork was drafted directly on the computer. The coloring as

the last step still maintained the established traditional

workflow and did not save any time in this respect.

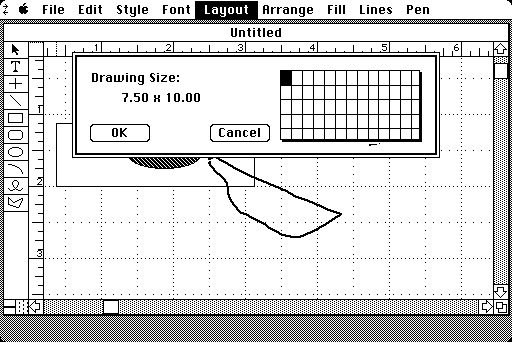

Figure 23: MacDraw on a monochrome Macintosh (ca. 1985).

The Typical Process in 2018

Today, we need to distinguish between comic books produced by

the "big two" commercial comic book publishers, Marvel and DC

Comics (and to a lesser extent, the next large publishers Image

and Dark Horse), and those comics produced by independent

artists or groups of artists.

Commercial Comics

Even at the time of writing this paper, the steps in creating a

physically printed commercial comic book have not changed

drastically compared to 1985, but the process is greatly

expedited. A writer writes the plot and the script and sends it

as an email to the editor who then provides all the changes and

forwards it to the artist.

This where the process becomes very disparate. Different artists

work differently. Some will still draw the artwork on paper

board using a pencil and then either ink it themselves or pass

it on to an inker to be embellished. Even if this analog path is

chosen, some artists will still use digital references or even

trace from printouts of digital sources. They might model

difficult background shots using 3D software and then draw from

this reference. In any case, the artwork is scanned into the

computer and sent as a digital file to the publisher for further

processing.

Two steps in the process have switched nearly exclusively to

digital: lettering and sound effects and the coloring of the

book.

Figure 24: An artist using a Wacom Cintiq 24"

(Source:

http://www.antcgi.com/2014/05/27/thoughts-on-the-wacom-cintiq-24hd/)

While a large part of the drawings for commercial comic books is

still produced using analog means, the tendency to produce

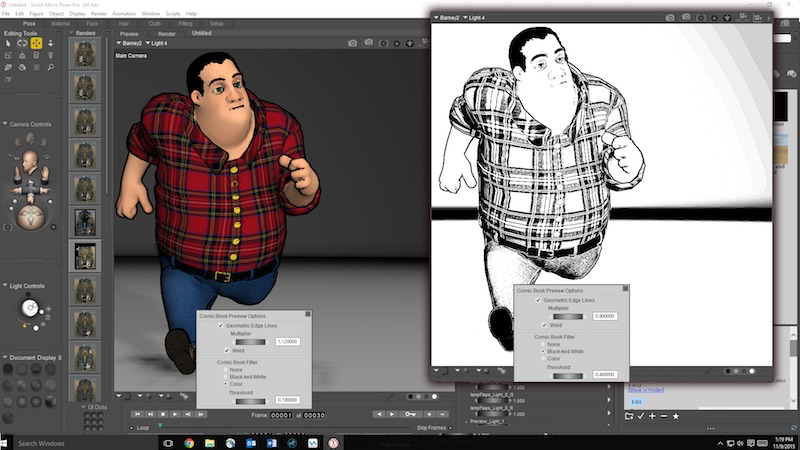

purely digitally is slowly prevailing in independent comics.

Artists either draft their artwork directly on a screen using a

Wacom tablet, Microsoft Surface, or iPad Pro or they sketch on

paper and refine their work digitally. Some artists use 3D

software to meticulously render their characters, props, and

backgrounds. Then they combine the components using paint or

layout software.

That being said, commercial superstar artists like DC Vice

President and one of the current Superman artists Jim

Lee and Green Lantern artist Ethan Van Sciver still

pencil and ink their work.

Even though exceptions do exist, to this day, the mainstream

process is still not fully digital with analog steps remaining

for drafting and inking. The process of coloring and lettering

are fully digital. One of the reasons for the pedantically

segmented process in commercial comics is strict editorial

control over every step. This not only allows the editor to play

gatekeeper, catching any potential quality issues or any part of

the commissioned work that might be inadequate or inappropriate,

it also allows the editor to keep an eye on the progress of the

comic book from the first word laid down to the finished piece

being delivered to the printer.

Strangely, this only partially digital production process needs

to end in a digital file for printers to handle. Even though the

sales of physical comic books are dwindling in 2018, digital

distribution of comic books through vendors like comixology.com

cannot yet compensate for the drop in sales.

Independent Artists

Again, it is hard to generalize; there will always be artists

who prefer traditional analog means. In some cases, they might

not even use pencil and ink on paper but could use a completely

different analog media, such as oil on canvas or collage or any

of the multitude of different techniques established over the

centuries.

Independent comics artists often work alone or, at most, in a

small team. They mostly do not have a support infrastructure, so

they do more on their own. This is one of the reasons why

digital production is more common in the field of independent

artists.

Due to the lack of editorial control, the process does not even

always need to start with a ready plot and script but can start

with sketches that evolve into a complete story. But for the

sake of comparability, let us start the digital process an

independent artist uses with the story creation (plot and

potentially script). They then might produce thumbnail layouts

of the pages to get an idea of the story flow and the necessary

number of panels. This might be done on paper or, already at

this stage, on the computer.

Then the digital artist completes the final stages with digital

tools. Outline art might be drawn similarly to previous

techniques with a sketch, a finer rendering of the sketch in

more detail, and then the final cleanup. But because they are

working digitally, they are not bound to the processes of

physical media.

After rendering the outlines, the color art can be produced

without delay or the need to change medium in the next step.

Lettering and sound effects are added. And the page is done.

Purely digital pieces can be distributed over the web; those

produced for print can be emailed to the printers for direct

printing.

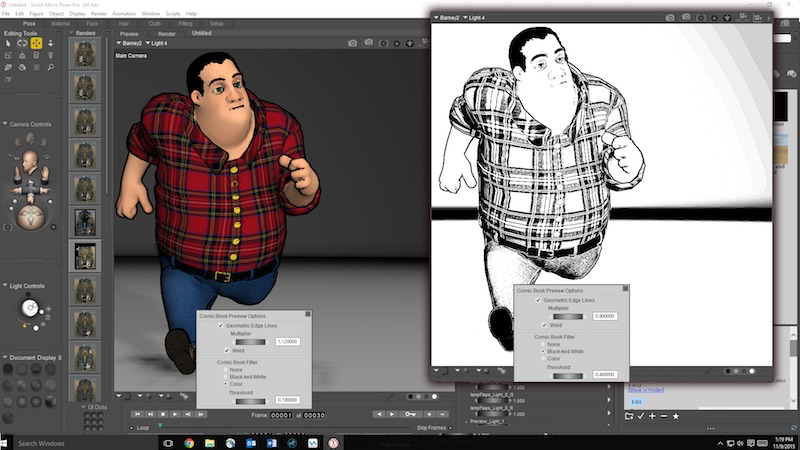

Figure 25: The Smith Micro application Poser allows artists to

pose 3D charactersand render them out as ink drawings for use in

their comics.

Comparing the Processes

In contrast, Shatter was limited by the available means

of communication, with disks with the digital materials being

mailed conventionally. But save for this, the whole process was

digital. The limitations of the printing presses made it

necessary to produce a hardcopy of the line art so that it could

be photographed for the plate-based offset printing of the day.

Coloring solely on a computer was not yet feasible on the

machines available in 1985, remaining a task to be done by hand

the traditional way.

IV. The Other First Computer Comic

"Someone asked me the other day what it feels like to see all my

'old stuff' reappearing, at long last, in digital. And I had to

smile because to me it doesn't feel like 'old stuff.'"

- Barbara Hambly

While Mike Saenz was the first to produce and publish a complete

comic book on a computer, other artists quickly followed. In

1988, German comic book artist Michael Götze created the

Das Robot Imperium comic album. This was the first

European comic created on a computer. He did not use an Apple

Macintosh to create this black-and-white comic, but instead the

Atari 520ST, an affordable competitor of the Mac that also came

with a mouse by default.

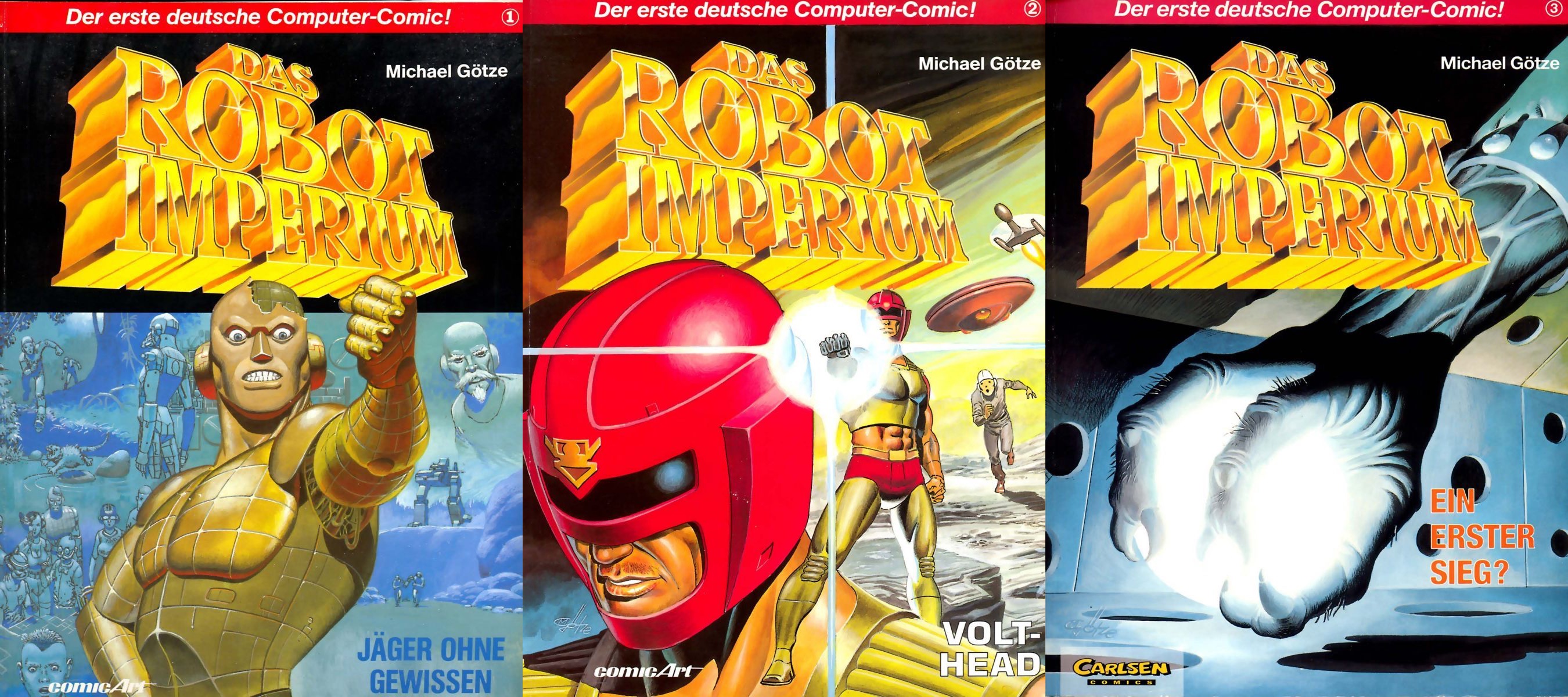

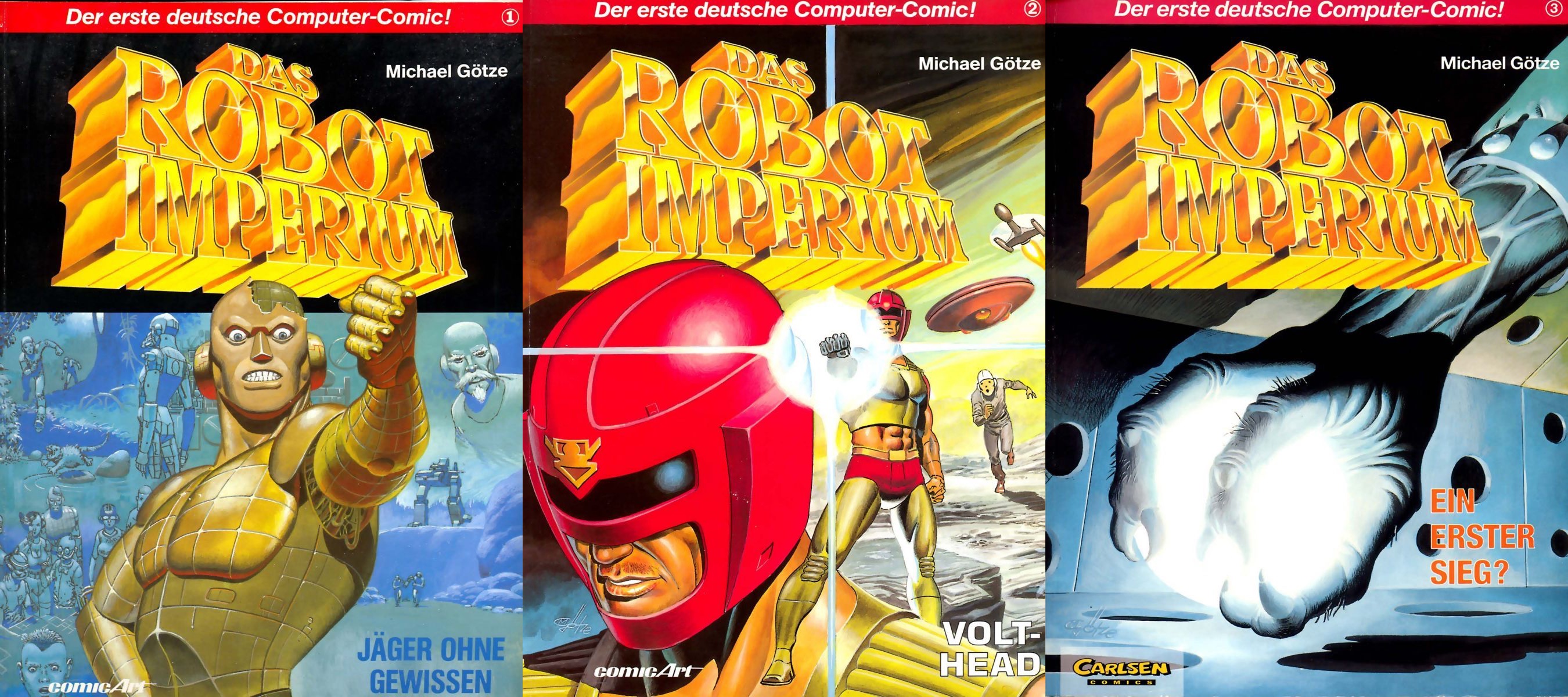

Figure 26 Michael Götze's traditionally painted covers for

Das Robot Imperium volumes 1 to 3 (Source:

Das Robot Imperium by Michael Götze, Carlsen Comics

Verlag, 1988, 1990, 1992)

Pixel Imperium

The comic's story chronicled the fight of a small group of

humans against the robots who ruled over them. Even in the

1980s, this was not the most original plot. Like

Shatter, this comic's main selling point was that the

artist created it on a computer.

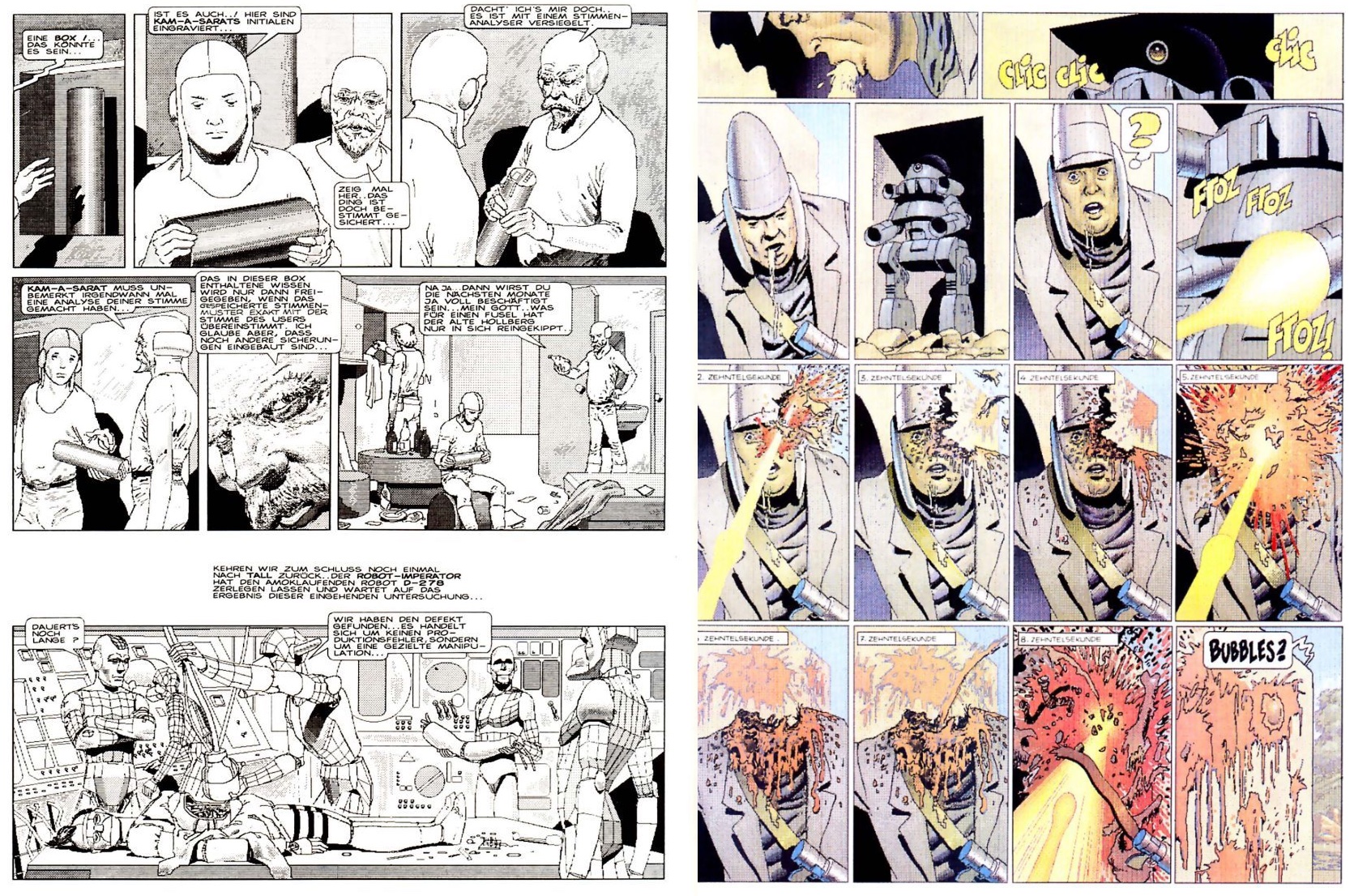

Even though the first volume of

Das Robot Imperium "Jäger ohne Gewissen" ('Hunter

without a conscience") eschews the use of color, it is a far

more lavish and elaborate work compared to Shatter. The

scenes depicted in the panels have depth and dimensionality. The

figures are not flat like in Shatter, Goetze renders

the characters' faces with much greater expressiveness. He took

much more time to produce each page than the fast release

schedule of Shatter would allow.

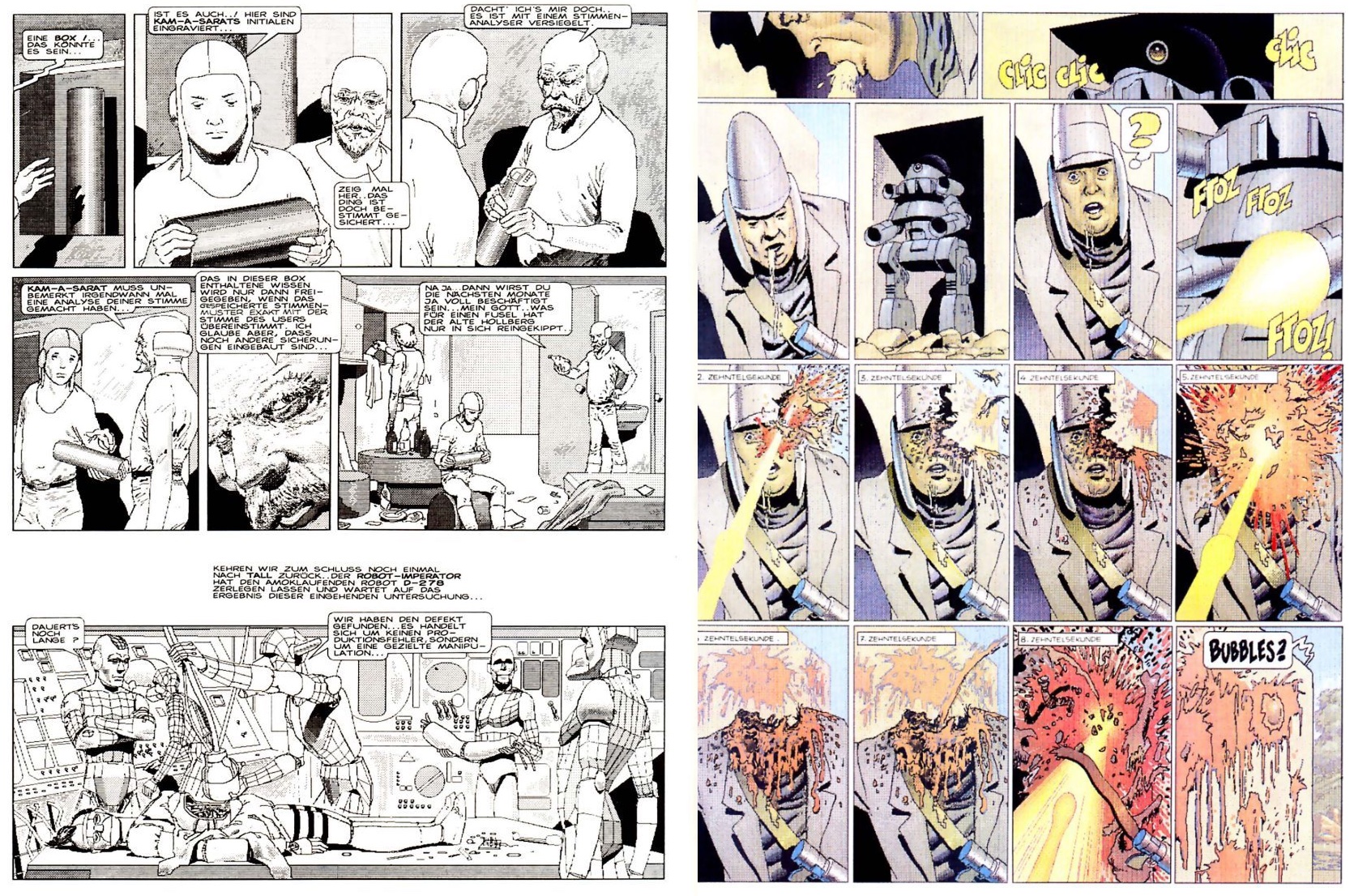

Figure 27: Left: interior BW page from volume one

Das Robot Imperium: Jäger ohne Gewissen. Right:

interior pages from volume two

Das Robot Imperium: Volthead

The Creation Process

On the Atari ST, Götze programmed his own 3D wireframe

application and special printing software using

GFA-Basic. In the application he called

Pixelart, Götze created 3D models of the human body and

put them in different poses. Then he combined the figures with

flat backgrounds. He also modeled props and mechanical

backgrounds like a command center in 3D. Once the 3D models were

created, he could place them in the scene and create complicated

perspectives with the wireframe models. Eventually, Goetze had a

library of objects that he could reuse.

He would laboriously touch up the images in the Atari ST paint

application D.E.G.A.S. Elite using the mouse to give

them the final polish.

Work on Robot Imperium started in 1986 on the first of

three volumes in the European album format. Götze drew the first

volume in black-and-white. The gradients were dot patterns

printed with a typical dot-matrix printer used in offices at the

time: the Epson FX-80.

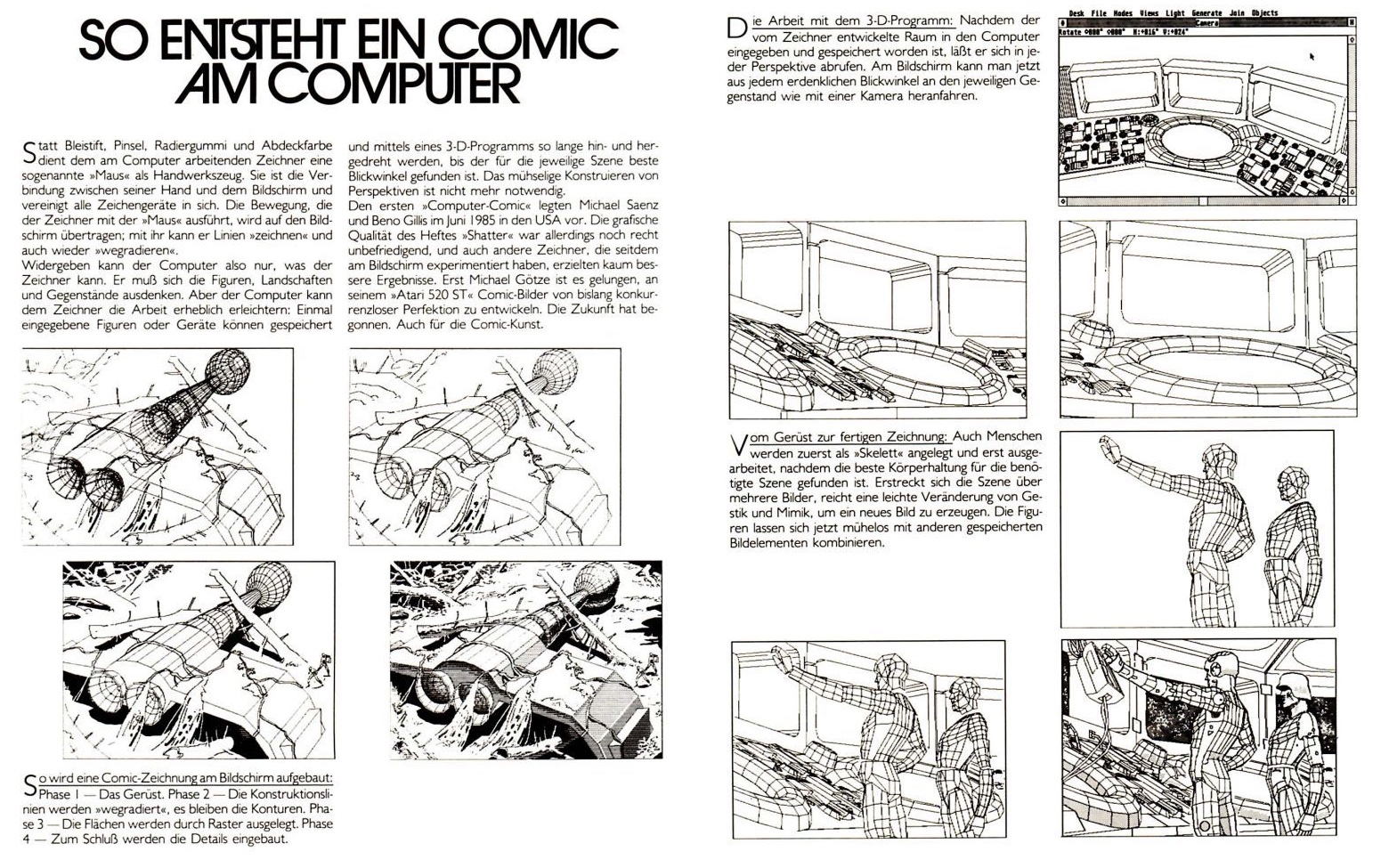

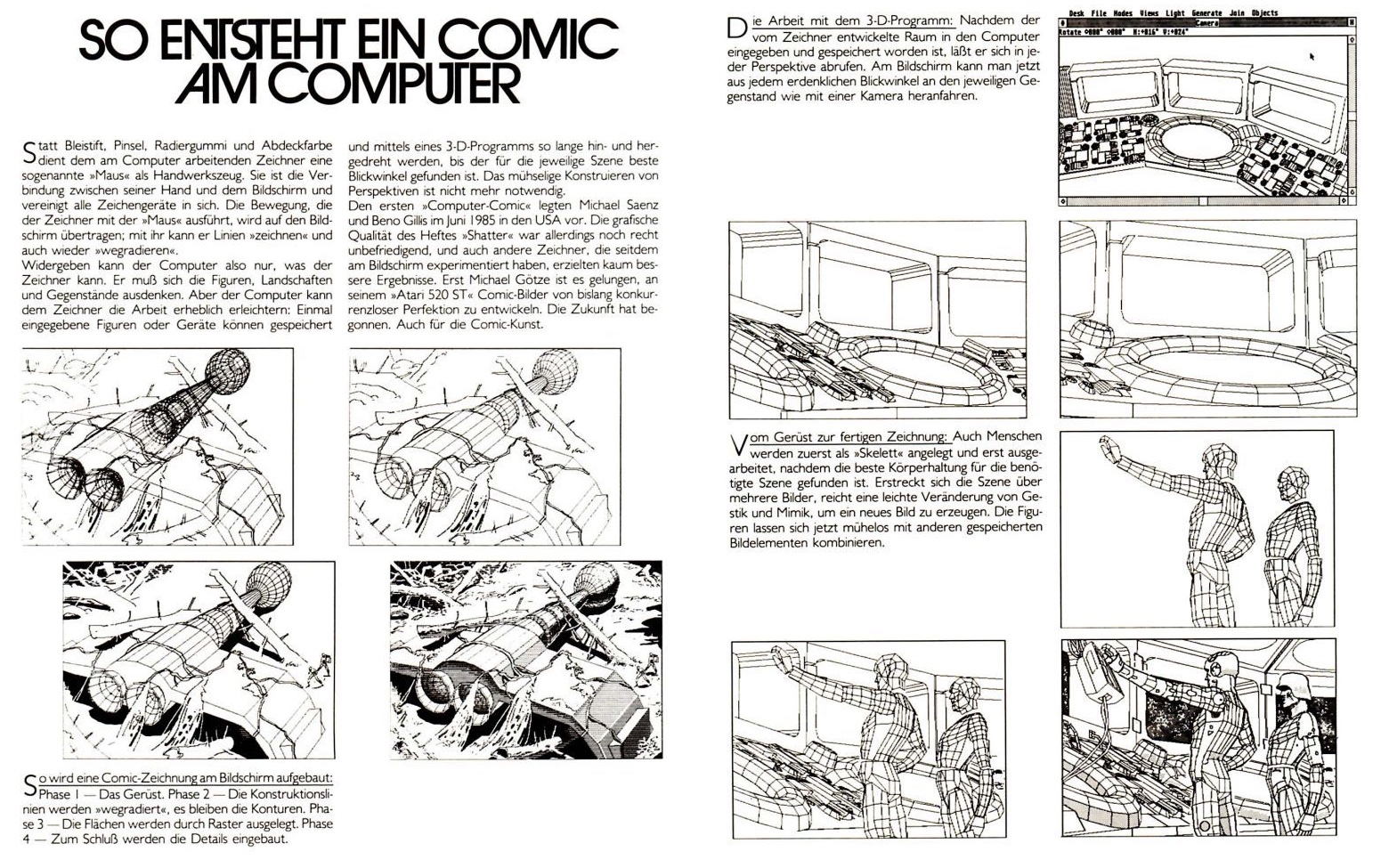

The back of the first two volumes shows a photo of the artist

Götze toiling away on his Atari ST. And the last few pages of

the first volume describe Götze's process for drawing the panels

on the Atari ST: "This Is How a Comic Is Made on a Computer"

("So entsteht ein Comic am Computer"). From today's perspective,

it might appear comedic that the process description includes a

short explanation of how a computer mouse works. There even is

mention of Shatter by Mike Saenz and Peter B. Gillis

(inexplicably, Gillis is referred to as Bernd Gillis in the

text). The piece's writer does not show high regard for Saenz'

computer art, calling it "unsatisfactory" and "experimental."

The most interesting parts of this description were the

screenshots of the individual steps in Götze's creation process.

They show how he places the rudimentary 3D model of a spaceship

over a rough sketch of the background foliage in a forest scene.

The wireframes of the spaceship show all sides, even the parts

that should be obscured from the viewer. Götze manually cleans

up the image, meticulously removing the lines that should not be

visible. Then he embellishes the manually-drawn backgrounds,

thus integrating them with the 3D model. Then he spots the black

areas and emphasizes individual lines to give them more weight.

Finally, he shades the image in dotted patterns for different

levels of light and dark.

Artistically, this painstaking process proved to be very

successful. The drawings are very much in the style of the

French bandes desinée of the 1980s. This speaks to the artist's

craftsmanship. Götze followed the first volume with the second

one titled "Volthead" in 1990, this time in full color. It was

printed on a dot-matrix printer in multiple passes with

different colored ribbons.

Figure 28: A description of the process of creating a computer

comic in Das Robot Imperium: Jäger ohne Gewissen

The Ghost of A Different Future

In 1992, Götze released the third volume "Ein erster Sieg?" ("A

First Victory?") with an even greater level of detail in his

drawings and an even greater level of artistic accomplishment.

Its slickness moved it so close to the traditionally drawn and

colored analog comics to make it indistinguishable at first

glance. This also meant that despite all the effort put into it,

the comic lost one of its most distinguishing features. It lost

the "look" of a computer comic.

Commercially, Das Robot Imperium ended up not being very

successful. It remains a testimony to artistic dedication,

adventurous graphical experimentation, and the stubbornness to

make the best use of the capabilities of a barely suitable

computer to achieve professional results.

V. Conclusion: Subversive History, Bright Future

"Someone asked me the other day what it feels like to see all my

'old stuff' reappearing, at long last, in digital. And I had to

smile because to me it doesn't feel like 'old stuff.'"

- Barbara Hambly

The Importance of Shatter as Media Art

Shatter is very much of its time. The

computer-generated art from the mid-80s is stiff and

un-lifelike. At the same time, it shows a mad energy that comes

from artists discovering what a piece of equipment can do beyond

what anyone thought before them. This energy might be fueled by

the intention to subvert the traditional comics production

process.

The art style is primitive by nowadays standards, but it is most

definitely the star of the series compared to the

run-of-the-mill story content. It is still visually interesting

to look at each page and wonder at the intricacies that Mike

Saenz and Charlie Athanas were able to eke out of their

Macintosh.

While only modestly entertaining as a piece of commercial

entertainment, Shatter is a cultural artifact and a

relic of a long-bygone era, with a good helping of quirkiness

and originality in execution. It shows the evolutionary step

taken to where technology has brought us today. To stay in

evolutionary terms, this comic book is the fish whose fins more

resemble legs, even though it has not yet fully left the sea. In

essence, the idea of Shatter is fascinating. The idea

that one day, comics might be produced digitally, but in 1985

Mike Saenz and Peter B. Gillis (and later Charlie Athanas) were

impatient and did not want to wait for technology to catch up

with their aspirations.

Archiving Shatter for Media Arts Histories

Even though Shatter was produced digitally, it was

always targeted at being printed. Its creators and the

publishing company sought to print it and distribute it as a

physical product. Preservation of individual printed copies is

subject to the same principles as preserving other kinds of

print media and periodicals: temperature- and moisture-regulated

archives and a complete absence of light during storage.

Aside from the physical medium, Shatter is one of the

earliest artifacts with the raw content available as digital

files. Unfortunately, the demise of First Comics Publishing has

made it unlikely for us to use this venue to obtain the original

digital files in the MacPaint format. It is certainly possible

to seek out the files from the original artists. The physical

media the files are stored on (disks or hard disks) might

already be corrupted after three decades of storage. If the

files can be found, then they can be archived in distributed

storage systems such as a cloud or a raid setup. In one of the

letters columns, the editor notes that for a small handling fee,

the publishing company would be prepared to send a disk with

digital artwork to interested parties. If any readers made use

of this, then digital copies might be stored away on disks

somewhere in the United States.

Apart from the files generated during production, there might

even be an animated digital trailer. According to one source,

the original artist even put together something of the kind that

was distributed on a disk. These might also still be available.

It exceeds the mandate of this paper to locate them.

Learning from Shatter

One might argue that it is not a matter of whether

Shatter is a good piece of entertainment, an

accomplished piece of art, or the culmination of a cultural

discipline. Even at the time of its creation, it never pretended

or aspired to be any of this. To many, Shatter exudes

the strange fascination that Eadweard Muybridge's sequential

photography of galloping horses and walking men and women in

Victorian times manifests, even though we have contemporary 4K

footage of the same motifs in much higher quality.

It can even be argued that Shatter is not an artifact

from the past that has had a great influence on how we create

and even read comics today. Its reach was not great enough to

have done so. But the technology it employed at the time

certainly had taken its first steps towards the total

digitization of the visual arts. Today we have become used to

seeing computer-generated graphics in film, in commercial art,

and in comics. The creators of Shatter were the first

to see these possibilities in the available hardware before it

was capable enough.

When we run original Macintosh software in emulation, software

such as MacPaint, MacDraw, and FullPaint, it is easy to lose

sight of the context it was used in at the time. Perhaps,

Shatter can open our eyes to this context. We shouldn't

frown upon software's limitations but recognize how artists in

the past used it for actual honest-to-God production work. They

did not see the restrictions, rather they saw the potential for

experimentation. And all of this with the pressure of

publication deadlines looming.

Exploring Shatter not only shows us the achievements of

the creators but also their omissions, failings, and blind

spots: They did not make any use of the nascent 3D graphics

already taking shape on the 16-Bit machines of the time. In the

year of Shatter's cancellation, comics artist Michael

Goetze, from Germany, had already been making use of 3D graphics

in his electronic comic Das Robot Imperium (Carlsen

Comics, 1988) on the Atari ST, a 16-Bit computer of a similar

generation as the Apple Macintosh.

It is easy to take Shatter at face value and only see

its clunkiness, its deficiencies, and the ineptitude in its

execution. As an audience and perhaps even as fellow artists, we

can all instead look at Shatter and ask ourselves how

much time and effort Mike Saenz and Charlie Athanas have put

into the work. At any point in their creative process, they had

the opportunity to give up and abandon this tedious and

thankless exercise. Perhaps, at some point, each one of them

stepped back from the nine-inch screen, with its monochrome line

art, and shook their heads, thinking how much effort they had

put into this work that to some audiences might look bad or

even, as Mike Gold put it, like "some amphetamine addict had

been given a box of a zip-a-tone." Maybe they thought how much

easier it might have been to take pencil and pen to paper

instead.

And perhaps they knew how "cool" they were, and perhaps they

felt how subversive their art was because they were at the

technological razor's edge in a world not yet ready for it.