The Commodore Amiga and its Undying Adoration by Anarchist Creatives

Why Is the Amiga so Beloved in the Demoscene?

The Commodore Amiga is a successful line of personal computers from the mid-1980s to 1990s. At the time of its introduction, the Amiga had superior graphics and sound capabilities compared to all other home computers. This magical computer enabled its young users to create graphics, music and animations with a level of sophistication that was previously unattainable in the home.

To this day, the Amiga holds a great significance in the demoscene, a niche subculture of developers, musicians and artists who create real-time audiovisual presentations called demos.

This essay investigates the gestation of the demoscene, the Amiga platform's revolutionary beginnings, its emotional resonance within a dedicated community, and its broader influence on the field of computer graphics and music. Why is the Amiga still one of the most beloved and significant platforms in the demoscene?

December 2023

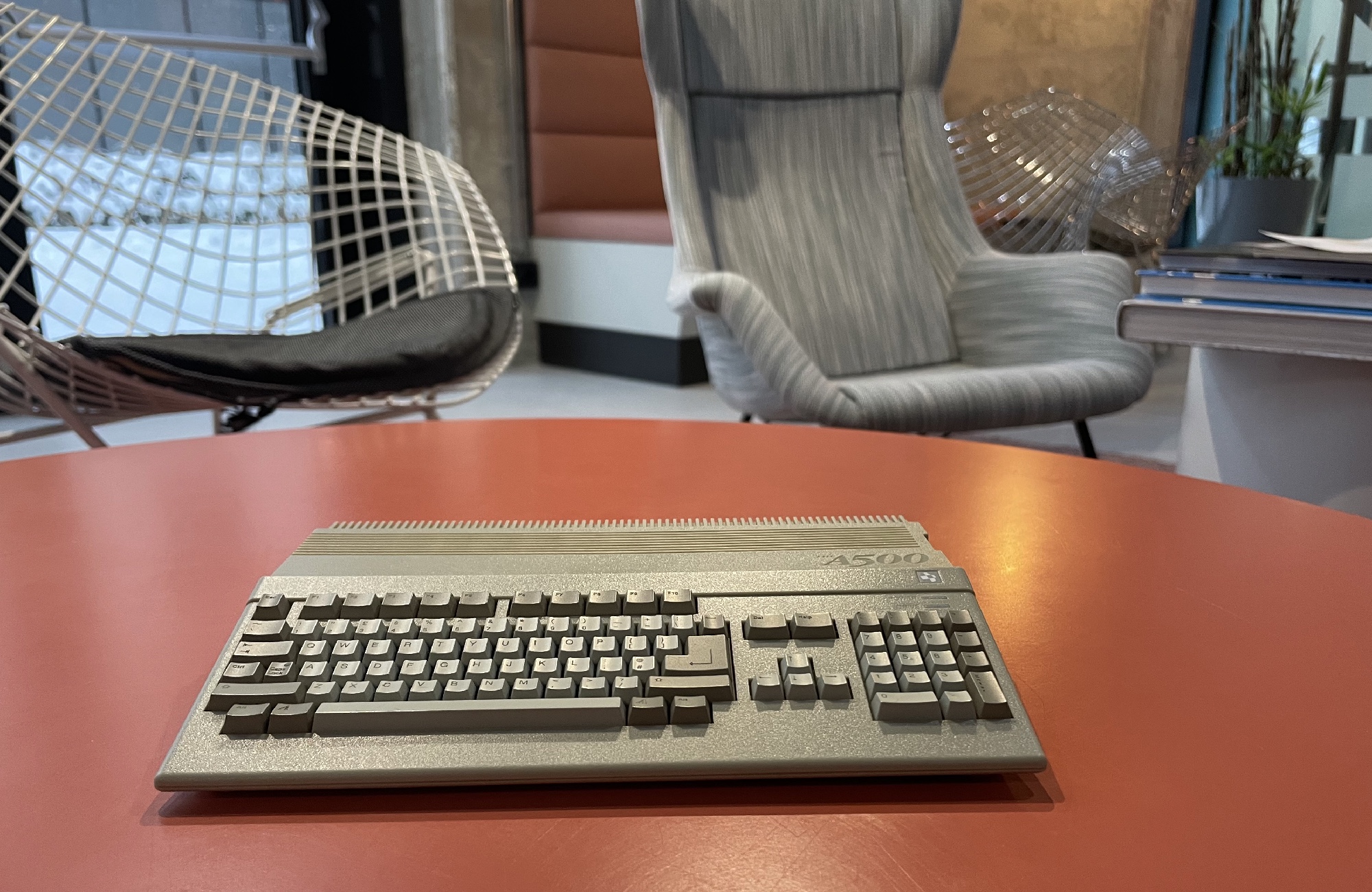

TheA500mini, a modern-day recreation of the Commodore Amiga 500

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

It is April 2023. In a large industrial event hall at the outskirts of Saarbrücken, a thousand people gather for Revision 2023, a demoparty.

The brick building used to be a power plant. Inside a vibrant and eclectic tech haven. Rows of tables stretch across the large space, each one laden with an array of computers that showcase the diversity of the demoscene community. These machines range from vintage models to modern high-performance setups, each uniquely customized to reflect the personality and skills of their owners.

Demosceners, immersed in their creative world, occupy these tables. They are a mix of programmers, graphic artists, and musicians, each deeply focused on their screens, coding, designing, or composing. The atmosphere is one of intense concentration, interspersed with moments of acceptance and exchange as participants share techniques, ideas, and admire each other's work.

The air is filled with bursts of electronic music. The ambient lighting, often dim to favor screen visibility, adds to the event's distinctive, almost otherworldly feel. This setting is not just a place for competition but a melting pot of collaboration, innovation, and celebration of the digital arts.

All eyes are drawn to the large screen above the stage, hovering like a portal to otherworldly realms. Each demo unfurls like a digital tapestry, weaving vibrant 3D animations, hypnotic visual effects, and pulsating rhythms into a seamless spectacle. The audience, a sea of shadowed figures, is captivated, their collective breaths held in anticipation as each new creation bursts onto the screen, a vivid dance of light and sound. In these moments, the room transcends reality, immersed in the boundless imagination of the demosceners, whose artistry turns code into poetry and pixels into dreams.

Suddenly, someone shouts, "Amiga!" The crowd erupts in cheers. Someone else yells even louder: "Amigaaaa!!!" Other members of the audience join in, shouting "Amiga!" into the receptive crowd.

Welcome to the demoscene. "Amiga" is the name of a computer older than half the audience at the demoparty. Let's take a look at the demoscene and the Amiga's role in it.

The Revision demoparty in Saarbrücken, April 2023 (Photo: Marin Balabanov)

1. What is the Demoscene?

The demoscene is a creative, enthusiast subculture of the computer arts. The main purpose of the demoscene is to create demos: fun, self-contained applications that present interesting music, real-time graphics and sound effects. They are a unique form of self-expression related to yet distinct from digital music videos.

Since the 1980s, demo makers have shown off their skills in programming and application design, painted and computer-generated graphics, as well as their skills in composing music or creating sound. The word "demo" is short for "demonstration" because the application demonstrates the capabilities of a computer system and the skill level of the demo's creators (and is not related to "demonstration" as a form of protest). [1]

Demos are freely distributed. At first, demos were shared among a small audience either on Bulletin Board Systems (BBS), or personally on disks through public domain libraries. In the past decades their distribution has moved predominantly to the web. Demos are usually installed on a computer and run locally on it to make efficient use of the computer's hardware resources. Demo libraries on Bulletin Board Systems and Mailboxes were the first archives of demos and are mostly lost due to the evanescent nature of their hosting platforms.

Today demos are developed for contemporary computer hardware, such as popular Intel-based systems that are suitable to run Windows, Linux and MacOS. But they are also created for historic, legacy computer hardware that has not been produced for many decades and is severely limited by modern standards like the Commodore 64 (1982 - 1994), the Atari ST (1985 - 1993) and, of course, the subject of this essay, the Commodore Amiga (1985 - 1996).

Pouet.net serves as a database and a social platform where demosceners can upload their demos, share information, and review each other's work. The website includes a vast collection of demos from various platforms, ranging from classic 8-bit computers to modern PCs, and it's a popular resource for both demosceners and those interested in digital art and computer history.

Despite the demoscene being predominantly a European phenomenon, at the very beginning, its precursor was part of the software piracy and cracking scene of the 1970s and 1980s in the United States. [2]

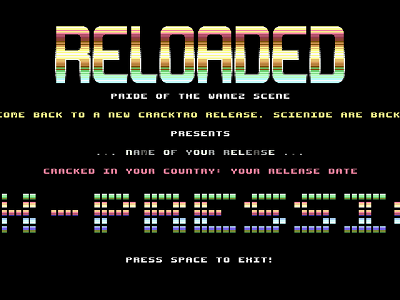

"Cracktro RELOADED Restricted Area" on Commodore 64

(Source:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5mKG1SrCPvQ

)

1.1 The Conception of the Demoscene: Showing Off as a Specialization

Let's wind the clock back to the late 1970s and ealy 1980s.

The software cracking scene originally started out on the first widely available home computer, the Apple II. This machine was successful mostly in the USA.

Even in the fledgling days of the commercial software industry, piracy was an issue. Commercial software applications and games took effort to produce and were sold for a profit. The To prevent the copying and free distribution of their software, software publishers added clever copy protection to their games and applications. Hobbyist software pirates reverse engineered the applications, found the parts of the code that were relevant to copy protection, and either deactivated this code or removed it completely. This was called "cracking", and thus the software cracking scene was born. [3]

In many cases the crackers also distributed pirated software themselves. The distributors called themselves "traderz" and "swapperz". Some crackers just wanted to crack the ever more intricate copy protections out of technical ambition.

Most of the pirated software consisted of games. Crackers wanted to show off that they were the first to defeat the copy protection, so they started to change the games' title screens or added their initials or a pseudonym to a game's default high score table.

This was all done in friendly competition between cracking groups. Eventually, the credits screens became more elaborate, completely taking up the loading screens, turning them into "intros" with graphics and music sometimes referred to as "cracktros". The members of cracking groups wanted credit for their effort. So they had their pseudonyms scroll across the screen together with messages to other cracking groups: these were called "scrollers".

Crackers and cracktro makers were usually young, some even in their early teens. This meant that many of the messages were full of bragging and juvenile posturing. They used cracker names like "Triad", "Ikari", "GCS" (German Cracking Service), "FCG" (Flash Cracking Group), the "Dirty Dozen" and the "Warelords". In the early days, many crackers also used three-letter acronyms because the high score tables of computer games were limited to three characters. [4]

Over the years, the cracking scene expanded to include different computer systems other than the Apple II like the Atari 8-bit computers, the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, the Commodore 64, the Amstrad/Schneider CPC and 16-bit machines like the Commodore Amiga, the Atari ST, and the IBM PC compatibles.

Software was distributed either person to person by copying the cracked programs on cassettes and floppy disks, by mail delivery, or was uploaded to a BBS like "Sharegood Forest" for others to dial in and download the "warez", as they started to be called. Occasionally, home computer enthusiasts would meet at meetings, called "copy parties". There they would exchange copies of their cracked games and applications. At these get-togethers, they also shared their tricks of the trade and demonstrated and explained their programming tricks and cracking techniques.

When they did not meet in person, they participated in one of the first online communities, albeit connected with each other using modems and acoustic couplers to mailbox systems and BBSs via dial-up connections. On the BBSs, they not only shared software and messages, but also text files with technical how-to's and information but also cooking recipes, poems, prose and "subversive" texts like "The Anarchist Cookbook", they called these files "philez".

Both the cracking scene and the demoscene started releasing "diskmags", periodically released disk magazines with text and graphics. Free of any editorial oversight and only fueled by their enthusiasm and the quest for recognition by their peers, the writers wrote about anything they were interested in. The predominant topics were computers and software. Intro makers, crackers, graphics artists, and computer musicians shared their knowledge, tips and tricks. Often, they would write about movies, books, comics, commercial music, and anything else that struck their fancy.

As the intros grew larger in size and became more complicated, they started to rival the size of the actual games they were attached to. Programming the effects, creating the graphics, and writing the music became their own disciplines detached from the cracking skills.

Some groups started to completely focus on the intros and stopping cracking software altogether. These were the first dedicated demos: floppy disks distributed with only the demo with computer art, animation, and music.

At cracking parties, the intro enthusiasts expanded their knowledge sharing their graphics creation, music composition and effects programming. They did this not for profit but for the recognition by the peers in their niche group. They wanted to gain the respect from others who actually understood what they were doing.

At cracking parties, they held their own intro/demo competitions, voting for the most impressive demos. These were awarded prizes by individual categories like graphics, sound, music and effects.

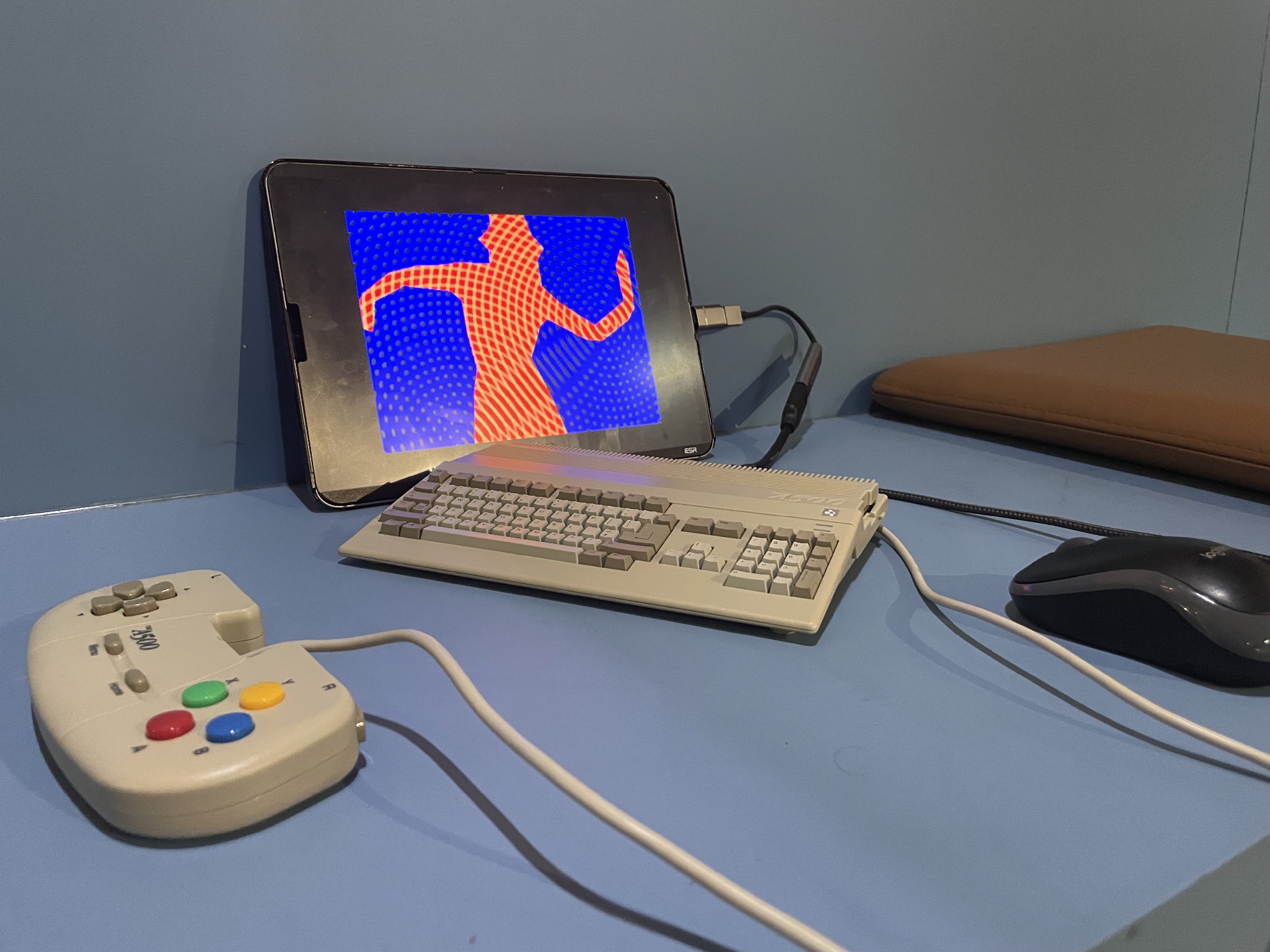

TheA500mini showing the demo "Jesus on E's"

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

1.2 The Scorpion and the Frog: How the Demoscene Separated from the Cracking Scene

Demos became a product in their own right, stripped of illegality by being dissociated from the cracking scene. Ironically, crackers started to crack and copy the demos made by the demo makers. Some crackers even added intros to the demos. After all, why not!?! They were hackers after all.

In his oral history of the demoscene, "Freax", writer Tamás Polgar identifies a point at which the demoscene separated from the cracking scene in 1989:

"Demogroups were only contacting each other and rarely crackers. Like there was a second scene. A known, great cracker's name was not so respected among demomakers, and vice versa. This separation was very noticeable during the 1989 Ikari-Zargon party. Ikari, thought that as the organizers of the party, they should win the demo compo so they disqualified their competitors Horizon and Oneway." [5]

At this cracking party, there was a large contingent of demo makers who participated in the competition. Polgar describes how the organizers who were all exclusively from the cracking scene simply rigged the competition for chief-organizer Ikari to win.

"There was nothing wrong with it for crackers as they were 'unknown' groups, and Ikari was a living legend - the top elite of the scene. Anyway, they were just demos. This outraged the demosceners and the organizers were furiously bashed in many diskmags and demo scrollers."

Just like in the story of the scorpion and the frog, at the Ikari-Zargon party in 1989, the crackers had "hacked" the competition to their advantage and made the demo makers lose with their submitted works. What did they expect? They were crackers.

Demo makers had long had fun making the animations, graphics and music of the intros as part of the cracking scene but not actually cracking any software. They decided to only make their demos and share them with people interested in them. Since the demos were their own creations, there weren't any issues of legality (beyond the occasional use of unlicensed samples in the music or digitized stills from films). They were interested in creating their own art, sharing it and gaining the recognition of their peers and admirers.

Therefore the demoscene became a separate subculture.

"We are Demo" by Offence, Fairlight, and Noice on the Commodore

64

(Source:

https://youtu.be/2XUxT2pyDos

)

1.3. Tribalism by Computer System: The Fragmented and Independent Demoscene

Another use of the word "demo" in the computer industry in the 1980s was for retail point-of-sale demonstrations of a computer's capabilities. Computer shops would have their machines on display and run graphical demonstrations on them for customers to see how capable they were. Sometimes these demos were produced by the computer manufacturers, though often shop owners used demos from the demoscene because they were much more impressive and pushed the limits of the computer hardware much further than even the manufacturers had thought possible.

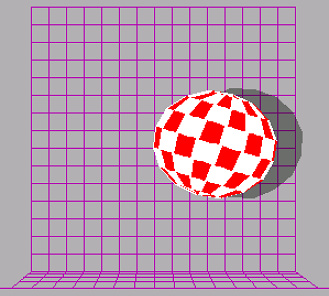

One particularly famous demo was the "Bouncing Ball" or "Boing Ball" by Dale Luck and R.J. Mical from Commodore. It featured a red and white checkered sphere that bounced in front of a blue background, demonstrating the capabilities of the Amiga's hardware for rendering and animation. It became quite iconic and even started to be used as a secondary logo of the Amiga itself.

"Bouncing Ball" by Dale Luck and R. J. Mical

(Source:

https://www.pouet.net/prod.php?which=27096

)

The technology of home computers advanced at a rapid pace. The 8-bit machines of the early part of the decade were succeeded by the far more capable 16-bit generation. All systems were bespoke hardware and completely incompatible with each other. Popular home computers for the creation of demos needed to have some graphics and sound capabilities: a text-only computer was not well suited for animation, graphics and music. Coders definitely had to know their way around the hardware. They didn't use a high-level programming language like Pascal or Basic. To eke out the last bit of performance from the computer they used assembly code, the last human-readable programming code before one resorts to pure machine code composed of ones and zeroes.

Creating demos began to require the participation of multiple people, including artists, musicians, and coders, not unlike creating a computer game. At the time, the various members of a demo group had to own the same computer system for their component parts to be compatible with each other and be able to be combined in a single demo.

Due to the still comparatively high costs, very few people owned multiple computer systems. You were proud of what you owned and some people became even so fanatical about their computer system of choice that they wanted to prove other computers were worse than theirs. Demo makers wanted to show off the strengths and capabilities of the machines they owned. This led to a sort of "techno-tribalism" or "postmodern tribes" where demo groups competed with each other not only on their machine of choice but also between computer systems. The demo makers would try to stretch the limitations of less capable computers by mimicking some of the technical achievements of later and more modern machines.

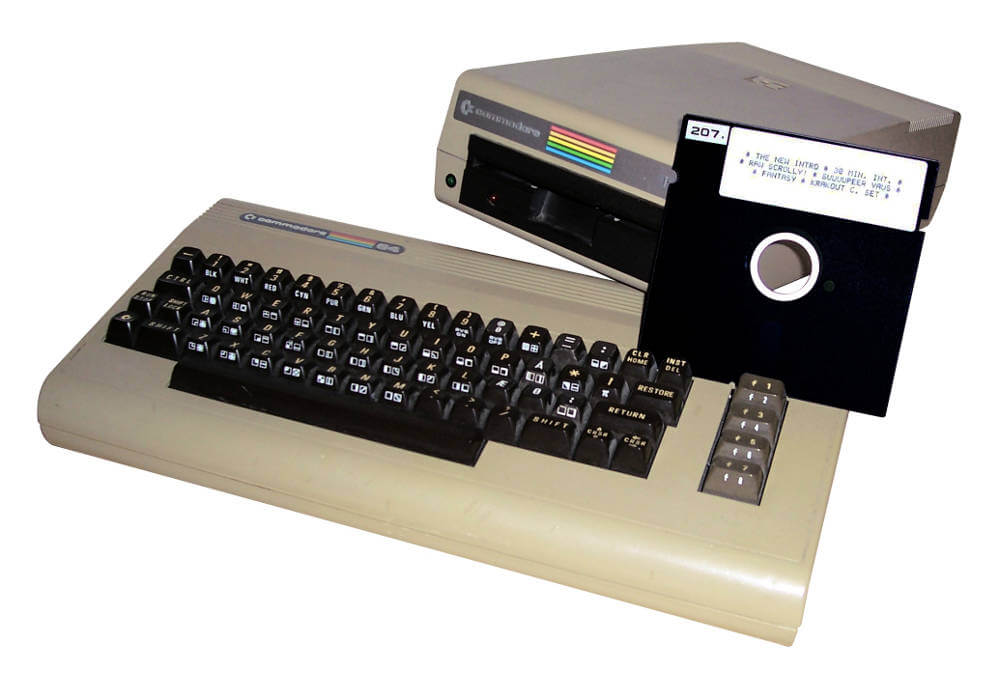

While crackers and intro/cracktro makers worked on many systems, the demoscene rapidly expanded on the Commodore 64, the most popular machine of the 1980s. As its name suggests it has 64KB RAM and its central processing unit (CPU) is a MOS 6510, a variant of the MOS 6502, which runs at a clock speed of paltry 1MHz . Without employing any software tricks, the C64 could display a total of 16 colors at a standard resolution of 160 x 200 pixels, though it also has a graphics mode with the higher resolution of 320 x 200 with more limited colors. To generate sound and music the C64 has a SID (Sound Interface Device) chip with three sound channels or voices. [6]

The Commodore 64 with floppy drive 1471

(Source:

https://developer-blog.net/c64-aufstieg-und-niedergang-einer-legende/

)

The limited hardware of the C64 meant that it could not show pre-recorded animations, so demos had to render all effects on-screen in real-time. They were procedurally generated, or had the movement patterns of objects stored in memory for animated characters called "sprites" to move around the screen.

2. Girlfriend with Benefits: The Commodore Amiga

In 1985, Commodore introduced the Amiga 1000. It was a quantum leap in performance compared to the 8-bit Commodore 64. It had a powerful 16-bit processor, the Motorola 68000 processor with a clock speed of 7,16 MHz. This new machine came with 256KB or 512KB of RAM and had amazing graphical capabilities. Depending on the graphics mode, it could display 32 or 64 colors out of an overall palette of 4,096 colors. At 320 x 200 pixels, the Amiga's lowest resolution was as high as the highest resolution that the Commodore 64 could generate. In it's highest resolution the "girlfriend" Amiga could display 640 x 512 pixel graphics interlaced with 16 colors. It featured far superior sound and music: capable of four-channel sampled sound.

When it was first introduced, the Commodore Amiga was framed as an artist's device, a tool for creating art. At the Commodore's presentation event for their new machine in 1985 in Lincoln Center, pop-artist Andy Warhol painted Debbie Harry on stage. [7]

The Amiga had custom chips for its graphics and sound that were begging to be explored by demo makers and exploited for even bigger and better demos.

Demo groups quickly recognized the potential of the Amiga and took to it like an artist paintbrush and easel or a musician their instrument.

Commodore Amiga 1000, the original Amiga

(Source:

https://www.oldcomputr.com/commodore-amiga-1000-1985/

)

2.1. Technical Capabilities

When the Commodore Amiga was released in 1985, it was ahead of its time. It had a powerful CPU and it had specialized chips, akin to co-processors, that elevated its capabilities above those of other home computers.

Joe Decuir and Ronald Nicholson described [8] the machine's key hardware innovations as:

- "Accurate NTSC and PAL video timing (led to genlock & Toaster)"

- "DMA driven IO - offloading the processor"

- "Programmable video co-processor, aka Copper"

- "Bit-blitter: sprite splicing, area fill, programmable ALU"

- "Bit-plane video, with flexible priority"

- "Hold-and-modify as a compressed color encoding"

- "4-channel sampled audio synthesis engine"

- "Configurable interrupt system based on video timing"

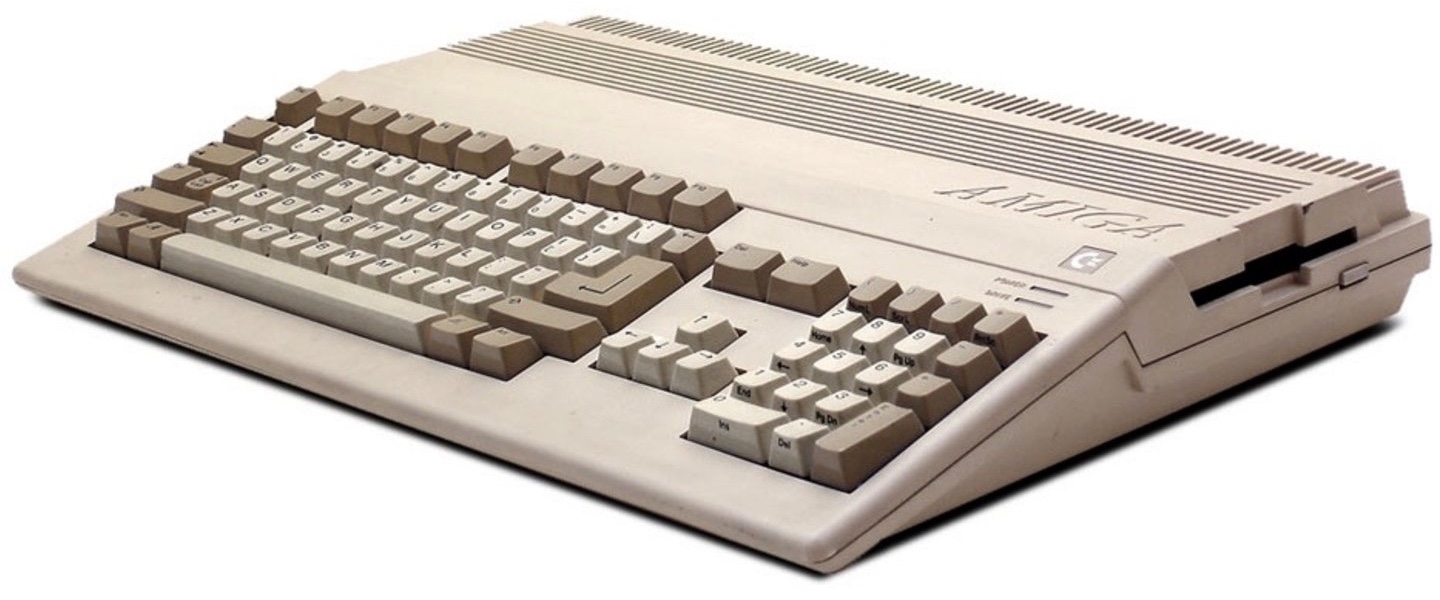

The Commodore Amiga 500, the most popular model of the series

(Source:

https://www.gamestar.de/galerien/commodore_amiga_500,97240.html

)

Essentially, this meant that home users in 1985 had features that only became common-place a decade later at a higher price:

- Arcade quality graphics in computer games

- Artists could produce images with up to 4,096 colors nearly on par with much later and more expensive VGA graphics on the IBM PC compatibles

- Musicians could produce near-CD quality sound and music

- The operating system was capable of multi-tasking years before Windows and MacOS.

In other words, "the Amiga had an advantage which took years to reach for PCs."

The Amiga 1000 was the first model released. It had a PC form-factor with a desktop case with room for a monitor and a separate keyboard. It was succeeded by the Amiga 500, which, despite its name, had the same capabilities but cost less to manufacture. This was achieved by consolidating some of the electronics on the motherboard and redesigning the case to house the keyboard, the motherboard, and the disk drive. Through the years, other models were introduced to address the professional market, such as the Amiga 2000 that could be expanded with the faster Motorola 68020 CPU, a larger PC-like desktop case, and multiple slots for expansion cards; the Amiga 3000 with the even faster Motorola 68030 CPU, improved graphical capabilities and a more modern expansion card system; and finally the Amiga 4000 as the last professional-level model that again improved on the CPU, the graphics capabilities, and the expansion options.

By the early 1990s, the Amiga 500 had become one of the most popular home computers in Europe.

"Eon" by Black Lotus on the Commodore Amiga (Source: https://demozoo.org/productions/202831/ )

Dale Luck, one of the software engineers who worked on the Amiga graphics library, says in the Popular Mechanics article "The Cult of Amiga Is Bringing an Obsolete Computer Into the 21st Century":

"I think the attraction in the programming community was the complete openness of the architecture and the ability to get as much performance out of the hardware as possible. It allowed for the development of truly revolutionary games and colorful and easy to use UI." [10]

2.2 Mastering Amiga Power

At home, Amiga was mostly used for playing games. The system had beautifully crafted games like Defender of the Crown, Shadow of the Beast, Turrican, Lemmings, and The Chaos Engine. Well-programmed games on the Amiga could match and sometimes even exceed the quality of arcade games.

Graphics creation was another popular use of the Amiga. There were many art packages, but the Deluxe Paint series, developed by Electronic Arts for the Commodore Amiga, was the most popular one.

"Deluxe Paint", the remarkable pixel art application by Electronic Arts (Source: The Amiga Museum )

Deluxe Paint was instrumental in showcasing the computer's graphic capabilities and revolutionizing digital art creation. Introduced in the mid-1980s, Deluxe Paint (also known as DPaint) became the de facto standard for pixel art and bitmap graphics creation, leveraging the Amiga's advanced graphics hardware. It had a user-friendly interface and range of features, including support for the Amiga's 4096-color palette, which allowed artists to create detailed and vibrant images with ease. DPaint's influence extended beyond hobbyist use. It became a tool in professional video game development, animation, and graphic design.

The software's ability to create animations, coupled with its painting and drawing tools, made it a precursor to many modern graphics programs. The popularity and impact of Deluxe Paint on the Amiga platform cannot be overstated. It became a system seller because it not only demonstrated the Amiga's technical capabilities but also empowered a generation of digital artists, setting a standard for future graphic design and image editing software.

Deluxe Paint showed the Amiga's 2D graphics capabilities, but the Amiga was also capable of rendering ray-traced 3D graphics (albeit very slowly).

One of the most influential ray-tracing packaged was Sculpt 3D. This pioneering 3D modeling and rendering software that played a significant role in the early days of 3D computer graphics. Home users had never had access to this kind of 3D modeling programs.

"The Juggler Demo" was rendered by Eric Graham on a pre-release version of Sculpt 3D (Source: https://www.pouet.net/prod.php?which=10776 )

Sculpt 3D opened up the world of 3D design and animation to a broader audience, leveraging the Amiga's advanced graphics capabilities. Sculpt 3D allowed users to create, texture, and render 3D objects with a level of ease and sophistication not previously available on home computers. Its ability to produce relatively high-quality 3D images on consumer hardware was groundbreaking and paved the way for the democratization of 3D graphics technology. Like Deluxe Paint, Sculpt3D also found use in professional environments, influencing early computer-generated imagery (CGI) in television and advertising.

Not long after the Amiga's original introduction, Eric Graham used a pre-release version of Sculpt 3D to create a ray-traced animation of a humanoid figure composed of shiny, colored spheres, juggling balls. This was released as the "Juggler Demo" and provided an early glimpse of the potential the Amiga held. In later years, upgraded Amigas were used to render the 3D space station and spaceships in the first season of the science-fiction series Babylon 5.

The Amiga found traction in the burgeoning "Desktop Video" market. Thanks to its accurate video timing, it could be used to overlay computer images over a video signal for titling and special effects. While this could be done "out-of-the-box" with an inexpensive Genlock device, the early 1990s saw the introduction of the NewTek Video Toaster. [11] This was a hard- and software solution to create computer generated graphics and edit them into video.

Creators from the demoscene leveraged the core hardware of the Amiga, trying to exhaust its graphics and audio capabilities. Yet the deeper demo makers delved into the system, the more surprises they found in the Amiga's hardware.

This gave creators room to implement their ideas, particularly demo creators. It was only the emergence of powerful consumer computers with enhanced capabilities in graphics and sound that enabled these "lay" creators to create their art. They demonstrated not only their aesthetic aspirations, but also their mastery of a specific and finite common toolset. Just as, at the time, artists in the commercial art world learned how to use computers to make art, young programmers, graphics artists, and musicians made art and, in the process, learned how to use computers as autodidacts.

In her seminal work on human-computer interaction "The Second Self", writer and researcher Sherry Turkle describes two categories of computer users: "soft masters" are creatively oriented computer users and use technology as a tool, while "hard masters" approach problems based on their technical skills. [12] In practice, the categories are not as cleanly divided, yet the idea can be used to describe the opposite directions that media artists and self-taught demo creators approach their tools from.

In his licentiate thesis, Markku Reunanen describes the Amiga demoscene as:

"Amiga demos of the 1980s mainly focused on numerous hardware tricks, and featured effects such as color bars aka 'copper bars', various kinds of scrollers and moving sprites, not too far from the C-64 roots. Wireframe and flat-filled vectors appeared already in the eighties and were perfected in the early nineties with features like pattern filling and transparency. Fast vector graphics almost became an obsession, and the programmers competed with the amount of polygons that could be displayed at a steady 50 fps, also known as 'in one frame'. The so-called design demos appeared halfway along the A500's lifecycle, increasing the audiovisual sophistication of demoscene productions considerably in the form of music sync, impressive still graphics, transitions between effects, and thought-out composition of visual elements." [13]

He identifies the highest point of the Amiga demoscene as the late 1980s to mid-1990s, with the Amiga being the successor to the Commodore 64 and itself succeeded by the PC as the ubiquitous platform for all endeavors, be they creative or business oriented. Yet decades later, there was a resurgence of the Amiga in the demoscene.

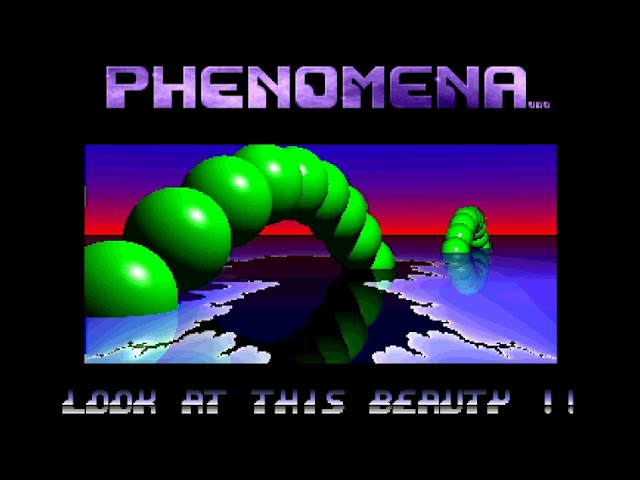

"Phenomena" by Enigma (Azatoth, Firefox, Tip, Uno) on the

Commodore Amiga

(Source:

https://youtu.be/iGpU3DicbLQ )

The first Amigas, the 1000, 500 and 2000 all had what was later called the "Original Chip Set" (OCS). As Aris Mpitziopoulos put it in his "Computer History: From The Antikythera Mechanism To The Modern Era":

"Amiga had amazing graphics and audio capabilities thanks to its dedicated circuits, called Denise (graphics) and Paula (audio). In addition to these two circuits there was also a third (initially called Agnus and after its upgrade renamed Fat Agnus), which provided fast RAM access to the other circuits, including the CPU. Agnus also incorporated a chip called blitter, and it was responsible for boosting the 2D graphics performance of Amiga. In other words, the blitter played the role of a co-processor and was capable of copying a large amount of data from one region of the system's RAM to another, helping to increase the speed of 2D graphics rendering." [14]

The slightly improved "Extended Chip Set" (ECS) was introduced with the Amiga 500+, 600 and 3000 and brought graphics modes with more colors and higher resolutions, as well as some internal improvements to access RAM faster. The final chipset was released in 1992 as "Advanced Graphics Architecture" (AGA), which put the Amiga 1200 and 4000 on equal footing with the much more expensive Windows PCs and Macs at the time.

The final architecture in development was the "Advanced Amiga Architecture" (AAA) but it was never completed. Commodore went out of business in 1994. [15]

Ultimately, IBM PC compatibles running MS-DOS and later Windows became the industry standard. Other systems like the Amiga became niches. Most failed fast. But others found their commercial renaissance like Apple with MacOS. In parallel to the commercial computing world, open source operating systems like Linux and BSD were developed. They were free to use and could be installed on any hardware. They dominated the server market.

The Amiga was one of the few systems that managed to keep a strong foothold with enthusiasts and hobbyists. It was a niche product without any official new hardware, but it was a niche product with a large and dedicated fanbase.

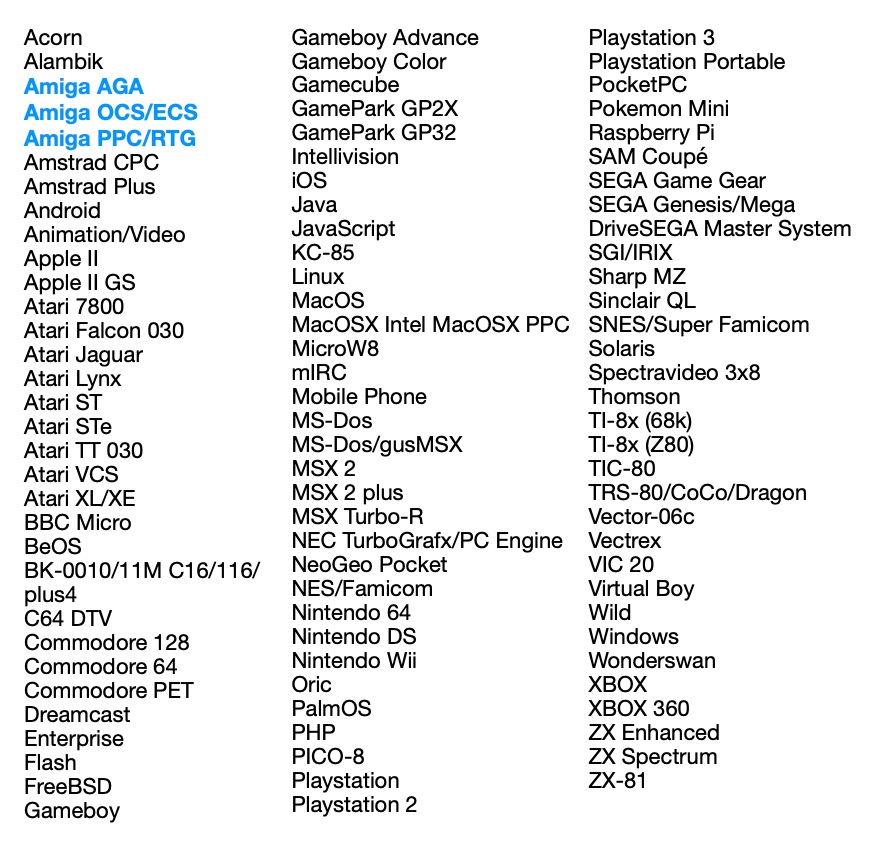

All 100 platforms with demos on pouet.net.

2.3 Dead Like Latin

Stephen Leary, the creator of the Terrible Fire accelerator board for the Amiga put it aptly in his interview for the Retro Hour Podcast: "The Amiga is dead like Latin is dead." [16] It is dead as a mainstream computing platform but still alive and well in the hobbyist sector. A cottage industry has developed around the Amiga to work on new hardware and software.

While the last officially produced Amiga was a 1994 reissue of the Amiga 1200 by the German company Escom that had acquired the rights from the bankrupt Commodore, this was not the last Amiga produced by enthusiasts.

Like Latin, the Amiga has gone through a number of minor evolutionary steps that have kept the platform alive. Users extended the life of their original Amiga hardware by building third-party accelerators into their machines so that their machine could keep up with the performance of contemporary PCs. On Amiga history sites, there are many dozens of historic accelerator cards listed. [17]

A number of potential successors for the original Amiga were released in the early 2000s by moving the platform to modern hardware. The AmigaOne X1000 and X5000 found a minor audience. They are built on a much more modern and powerful platform with PowerPC CPUs just like the ones used by Apple Macs from the mid-90s to mid-2000s. Some configurations are equipped with a graphics card that is capable of retargetable graphics that are similar to the ones in PCs and Macs of the early 2000s. Ironically, these much more capable machines do not feel like Amigas because they are too similar to machines running Windows, Linux or MacOS. [18]

The AmigaOS operating system was ported to the PowerPC platform [19] and was forked as MorphOS [20] and AROS [21]. Numerous recreations of the Amiga as Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA) have been created through the years ranging from the MiST in the early 2010s to the MiSTer in 2019. [22] The most impressive FPGA-reimplementation is the Vampyre card that not only accelerates old Amigas but also expands them to be compatible with modern day monitors and input devices. [23] In parallel, officially licensed emulators have been released for modern Windows PCs and Macs that enable users to run their old Amiga games, applications and demos on contemporary hardware. [24]

Two different projects based on the Raspberry Pi target different uses: The PiStorm acting as a CPU-replacement for classic Amigas, boosting their performance significantly at a low cost. [25] Amibian turns the Raspberry Pi into a low-cost replacement for a complete Amiga system booting the Pi directly into AmigaOS. [26] And finally the A500 Mini was released in 2022, a tiny recreation of the original Amiga 500 with a preinstalled games library and a joystick for modern day retro gamers. With a software update and the installation of AMiNIMiga, you can turn the A500 Mini into a fully usable Amiga. The manufacturer, RetroGames Limited, even announced a larger recreation of the Amiga to be released in a year or two. [27]

Despite an official lifespan of only a decade, the Amiga hardware scene is alive and well within the enthusiast community.

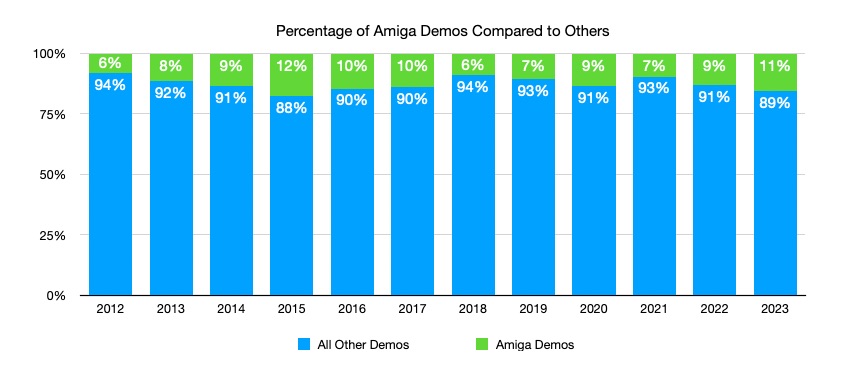

Amiga Demoscene Releases 2012 - 2023 (2023 until end of Nov.)

(Data source:

pouet.net)

The Amiga demoscene, however, is not only alive but thriving. The number of demos released every year has been steadily increasing since 2011. This is how the writers at Editions64K put it in their description for their upcoming book "Demoscene the Amiga renaissance, Volume 3 1997-2023":

In 1991, 2266 Amiga demos were released making up nearly 50% of all releases. By 2001, that figure was 170 - just under 10% of releases that year. Naturally demographics had a strong influence too, as the once-young sceners had to prioritize jobs, family and other commitments instead of slaving away to create their unique blend of art and science.

For a decade, the Amiga - and indeed the overall demoscene - was moribund. The 53 Amiga releases in 2010 made up less than 5% of the total demoscene output.

2011, for the first time in a decade, the number of Amiga productions increased, despite the overall number of releases decreasing. And this trend continued, with over 100 demos released every year from 2014 onward. (As an aside, the C64 has followed a similar trend, with its leanest year in 2009 but growth since. PC productions have however been on a downward trend since then.)

Demos were back. The demoscene is back. In 1995, AGA overtook OCS demos in terms of the number of releases annually... until 2011, when OCS took over, and hasn't dropped back since. In 2021, just 10% of Amiga demos were AGA, with the rest being OCS.

This means that not only do more demo-makers choose the old and deprecated Amiga platform to create their demo art, but they choose the older "original" chipset (OCS) instead of the more advanced AGA chipset that provides greater graphical and processing capabilities. This is a deliberate choice by the demo-makers to focus on the core capabilities of the original Amiga and to limit the capabilities of the platform.

They are interested in the challenge of hardware-limitations.

From 2012 to 2023 a total of 39 demos were released for the more modern Amiga platforms that use a PowerPC CPUs and/or retargetable graphics (RTG) that are comparable to modern graphics cards and GPUs.

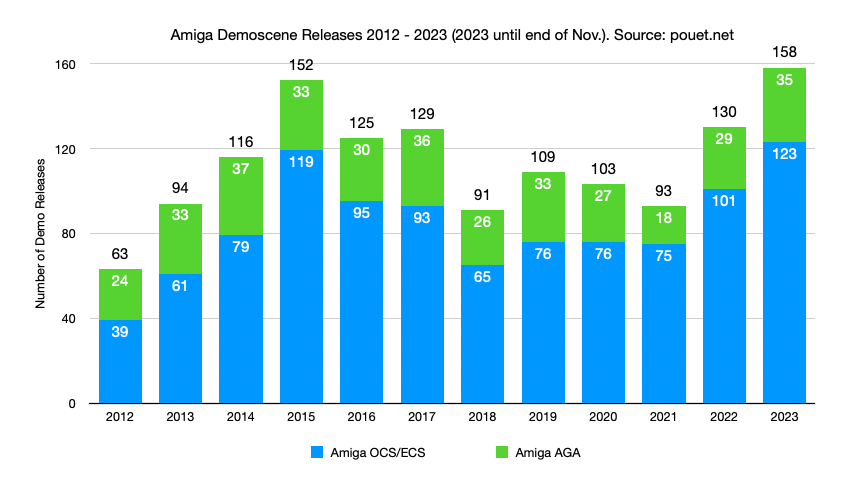

The total distribution of all demos among the top platforms from

2012 to 2023.

(Data source:

pouet.net)

Let's take a look at the numbers for the largest platforms on pouet.net.

- 16,323 total number of demos released from 2012 to 2023 (again 2023 only has data until the end of November).

-

3,740 Windows demos from 2012 to 2023.

22.9% of all demos released. This is on the Windows platform that is not only alive but the most used OS in the world with hundreds of millions of units sold. -

3,084 Commodore 64 demos from 2012 to

2023.

18.9% of all demos released. This is on the best-selling historic computer of all time with total sales of 20 to 30 million units. -

1,402 Commodore Amiga demos (including

OCS/ECS, AGA and PPC/RTG) from 2012 to 2023.

8.6% of all demos released. This is the "dead" and defunct Amiga platform with total world-wide sales over history of 4 to 5 million units. -

1,175 MS-DOS demos from 2012 to 2023.

7.2% of all demos released, just for comparison for another "defunct" platform that had a much larger user base than the Commodore Amiga.

Percentages of Amiga demos compared to all others over time.

(Data source:

pouet.net)

3. Demoparties and Subculture

Demoparties are an essential component of the demoscene. Demosceners congregate at a demoparty in person. These events are like a cool fusion of tech conferences and art festivals.

Picture a bunch of creative folks - coders, graphic artists, and musicians - hanging out with their laptops, Amigas and gear, all busy crafting and showcasing amazing digital art and music. There's this buzz of creativity in the air, with everyone sharing ideas, geeking out over each other's work, and just having a great time. Additionally, participants show off their creations on big screens during epic competitions, and everyone is just blown away by the talent on display. Demoparties have a chill, friendly vibe, where everyone is united by their love for digital art and technology.

The organizers of the Revision 2013 demoparty include a definition of demoparties for first time visitors:

"A demoparty is - on the first glance - like a LAN party. Depending on the size, a few or hundreds of visitors may bring their computers and set them up at the location. Unlike a LAN party, demoparties have an emphasis on creativity. Attendants are encouraged to compete in scheduled competitions (referred to by demosceners as 'compos'). These 'compos', spread out over the length of the party, are in categories that allow the attendants to showcase their artistic talents with the use of computers. In short: a demoparty is a multimedia art festival that usually lasts for several days." [28]

The Revision 2023 Demoparty in Saarbrücken

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

Demoparties are not only a place to meet other members of the demoscene to exchange information, they are also very much a place of competitive collaboration and friendly rivalry where the reward for winning is an increase in one's reputation. Reunanen describes the competitive aspect of demoparties:

"The demoscene is in a constant state of competition, which is exemplified by numerous practices of the community. To get to the top and acquire fame one needs to impress, win, and be connected." [29]

One of many original Commodore Amigas at Revision 2023

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

3.1 Demos as Electronic Graffiti and Digital Art

The demoscene shares intriguing similarities to the graffiti scene, making the term "electronic graffiti" a compelling, if not entirely accurate, metaphor for demos.

Both originated as underground movements, with graffiti emerging as street-level art. Each values technical skill and distinct styles, whether in programming and digital artistry for demos or spray painting techniques for graffiti.

Both communities thrive on creativity, identity, and a sense of fellowship, often gathering at events like demoparties and graffiti jams. While they both embody elements of counter-culture and challenge traditional art norms, a key distinction lies in their legality and public perception; graffiti often overlaps with vandalism, whereas the demoscene generally operates within legal boundaries.

Demos are new media art, yet demos are not widely seen as art, mainly due to their niche status. Reunanen describes computer demos as a category of new media art:

"By definition, demos are new media art: creative multimedia made with digital tools. However, there exists a gap between the demo community and the different genres of media art."

He describes them as a subcultural niche within new media art which makes the demoscene far less exposed to a general audience than other forms of art.

He goes on to identify the three major reasons for this niche status: [30]

"The first notable difference between demos and other forms of digital art is the limited scope of forms demos can assume: there are strictly defined categories of artifacts, pedantic competition rules and platform restrictions."

There is a formalism, a categorization in the demoscene that owes more to its technological roots than its artistic aspirations. This seems to be counter to the perceived freedom of the arts.

Reunanen proceeds to describe the second reason for the demoscene's niche status:

"The audience also has clear expectations concerning the content, acceptable frame rate and the style: what is demo-like and what is not. Another defining characteristic of computer demos in comparison to, for example, net art, game art and digital installations, is that they are hardly ever interactive, not even participative. Demos are meant to be watched, not touched, which connects them conceptually to digital video."

The established audience in the demoscene are familiar with the conventions and have tuned their expectations accordingly, they "get" what the technical achievements of individual demos are, something that is not and often cannot be communicated to an audience with only a passing interest.

And finally, Reunanen identifies the demoscene's self-infliction of its niche status:

"The persistently underground nature of the demoscene separates it from many forms of digital art discussed above. The exclusive nature of the community tends to keep its artifacts inside the borders, out of sight of the outsiders."

This speaks to the great role of demo archives in the identity of the demoscene. They are often the only way an interested audience can casually investigate the topic, the only lasting traces of the hard work of the demo makers, and ultimately the final resting place of its artefacts. The demo creators are also the primary audience of demos created by others, they draw their inspiration from their peers and at the same time feed back into the scene with new ideas and new technical achievements.

As mentioned above, pouet.net is a large archive and quirky community website. DemoZoo.org is the more modern archival effort of the community. The actual demo files are often stored on scene.org or GitHub with video captures of demos hosted on Youtube. The Demoparty.net website is the most comprehensive listing of demoparties around the world. There are many more websites related to aspects of the demoscene, but another one that unites the scene is id.scene.org, acting like the demoscene's own cross-platform authentication service. All these tools and platform are built and maintained by enthusiasts, how could it be otherwise?

The more mature the demoscene becomes, the more some of its members seek recognition from the mainstream. And they took initiative to make this happen.

The demoscene as a whole is the first digital subculture to be legitimized on UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage. In 2020, Finland added its demoscene to its national UNESCO list and in 2021, Germany also added its demoscene to its national UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage, and in 2023 the Netherlands followed suite. This is how the "Art of Coding" initiative to legitimize the demoscene announced the successful validation in Germany:

"Today on the suggestion of the national UNESCO expert committee, the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs decided to accept the Demoscene as German intangible cultural heritage. The decision acknowledges the long and living tradition the Demoscene has in Germany, with Revision, Breakpoint, and Evoke among other demoparties shaping the landscape of major international gatherings of the demoscene for decades … This will also help to shed more light on the amazing history and achievements of the Demoscene, will help to preserve it, and also give a push to invigorate everybody in these harsh times of continuous lockdowns encouraging new members from all kinds of backgrounds to join the scene as creators and connoisseurs." [31]

This recognition not only celebrates the innovative spirit of the demoscene community but also generally highlights the evolving nature of cultural expressions in the digital age. It underscores the idea that artistry and cultural significance are not confined to traditional forms and mediums, but also thrive in digital and technological realms.

As the DJ plays techno tunes like he was beamed to the present directly from 1990s, the dancefloor errupts with the spastic shakes and contorted twists of demoparty participants (Photo: Marin Balabanov)

Official acknowledgment is crucial for the preservation and documentation of digital art history. The demoscene's roots in the early days of computing have significantly influenced various aspects of digital and popular culture globally. By recognizing it as a part of the world's intangible cultural heritage, cultural institutions emphasize the importance of preserving this digital art form for future generations. It ensures that the origins, evolution, and impact of the demoscene are understood and appreciated, thus securing its place in the annals of cultural history.

Additionally, the official recognition of the demoscene has several beneficial implications. It enhances the visibility and support for the demoscene community, potentially attracting new audiences and fostering more support and funding for digital art initiatives. This confirms the cultural diversity and global influence of the demoscene. It highlights its role in shaping various elements of digital culture. Moreover, it validates the efforts and creativity of the whole demoscene community, acknowledging their contributions to the broader sphere of cultural and artistic endeavors.

Official recognition in so many countries is not just a nod to the past but also an encouragement for future innovations in the realm of digital creativity.

"State of the Art" by Spaceballs running on TheA500mini

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

3.2 Aesthetics and Limitations in Demo Art

Over the years, many aesthetic traits have become mainstays. Demos appropriate images from media and popular culture, including sci-fi and fantasy movies, computer and video games, and comics.

Some demos move large numbers of animated sprites along different motion patterns, as well as gradient bars and generated blobs of color that transparently overlay each other. Scrolling messages with outlandish fonts, some barely readable but stylistically amplified are a common method to convey text content. A large part of the demoscene in the past decades dedicated itself to generative 3D art with vectors either flat shaded, gouraud, or phong shaded.

Even though pre-recorded and pre-rendered animations are not explicitly disqualified from being used in a demo, they are frowned upon because one of the defining aspects of a demo is that it runs in real-time: everything is generated on the fly. As Lassi Tasajärvi put it, the difference between demo art and a pre-recorded animation is the same as the difference between theater and a movie. [32]

In his doctoral thesis "Kunst, Code und Maschine: Die Ästhetik der Computer-Demoszene", Daniel Botz describes the real-time aspect of demo art as:

"The implications of the real-time aspect are among the most difficult principles of the demo scene to convey. From a purely phenomenological point of view, visitors to a demo party who attend a demonstration of demos on a large screen cannot tell whether the projected images and amplified sounds are a played film file or an executable program file. Even if the viewer looks at what is happening on their own computer screen, as was the rule in the early days of the scene, the processes within the circuits remain hidden from them and cannot monitor the real-time aspect with certainty.

The awareness of the synchronicity of the event, the 'here and now', is essential for the sensual experience.

The optimal way of looking at a computer demo presupposes an awareness that creates the McLuhanian extensions of the body through the machine and thus its limits and possibilities in the receptive state. Even the expert viewer trained in demos has no distant certainty about the actual possibilities of the machine, but rather a vague but sensitive sense of the limitations of 'his' hardware. Insofar as a production follows the dictum of real-time executability, the viewer can sensually relate the effects and content presented to these perceived limits. He does not experience a demo as a spatially and temporally separated product, but as an actual process in which the computer takes on a far more active part than playing back data as a film. The aspect of creation versus pure reproduction and the passive participation of the viewer in the creation under the given conditions make the difference between a film showing and the execution of a computer demo. It is therefore logical when Lassi Tasajärvi compares a demo with a theatrical event than with a movie because of this aspect of the 'live performance'." [33]

Another powerful aspect of the demoscene is the constant struggle to overcome limitations. These can be hard restrictions set by using the limited hardware of old computers or by artificially inducing limitations of memory size or time limits.

Coders can potentially understand all aspects of limited hardware like the Amiga. It will still take a lot of smarts and effort, but once achieved they can utilize the hardware much more effectively.

In his master's thesis "Shattering the Limits - How Technical Limitations Pushed the Early Demoscene to Produce Digital Art", Marin Balabanov (yours truly) describes the demo makers drive to overcome limitations as the most core motivation for their art and that limitations breed creativity:

"Limitations are external to art and to the artist. Not everyone who pursues an endeavor may encounter these challenges. Rather, they are restrictions imposed by the laws of nature, the laws of a country or government, or technical limitations.

They are the color that you need but cannot find, the sound you hear in your head but cannot produce with the instruments you have, the thoughts you want to express but are silenced by authority. They are the space you need to create but cannot find.

Limitations are much more concrete where computer demo art is concerned. Particularly, in the early days of the home computer revolution, computers were not very capable. They had memory restrictions, displayed their graphics in strange ways, and produced unappealing sounds. It took an artist, programmer or musician who really knew how to handle the hardware limitations to conjure beauty out of the machine.

The demoscene has instrumentalized limitations as means to generate creative solutions and as a motivation. They have 'weaponized' an aspect of human ingenuity: to see a set of limitations and at first be taken aback, say they are impossible to overcome, but then through hard work, creativity and sometimes blind luck, nevertheless find means to overcome the limitations or, in the least, make them no longer matter." [34]

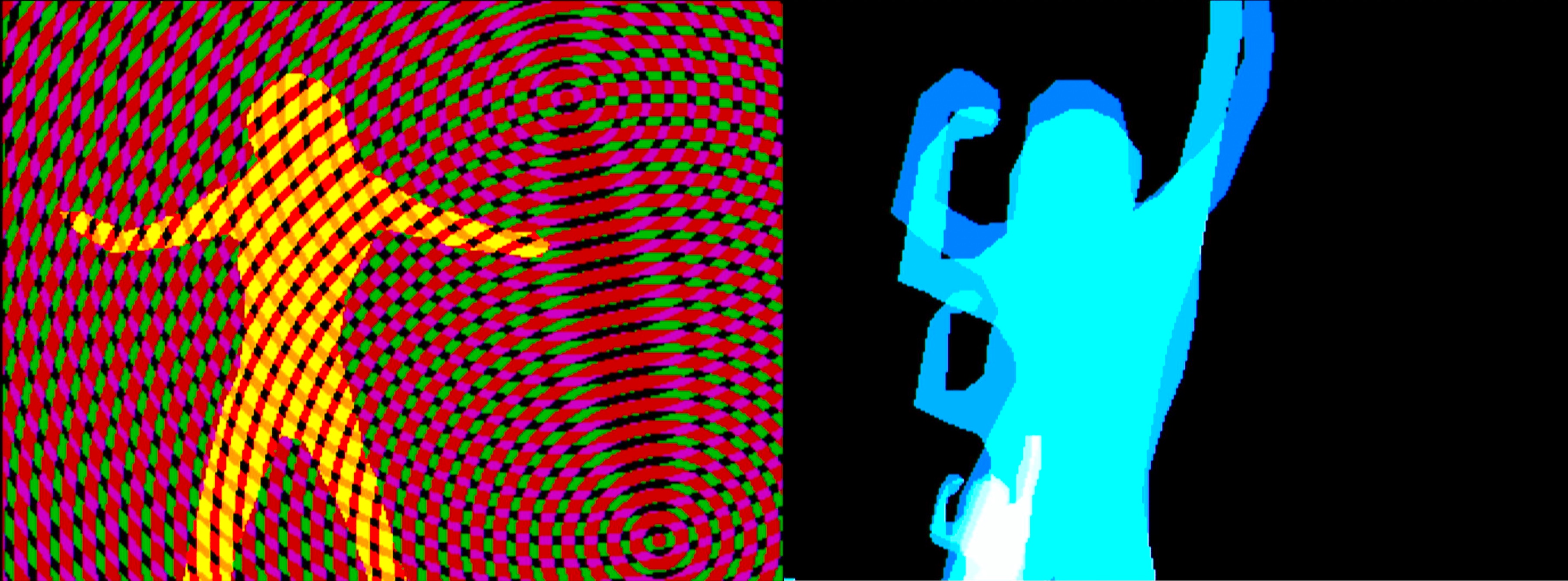

"Hardwired" by Crionics and the Silents (screenshots)

3.3 The Good, the Glad and the Innovative

Looking back over the decades, the demoscene has come very far. It has become an officially acknowledged digital subculture whose members produce real-time media art as computer demos, driven by their desire for recognition among their peers. A historic segment of this subculture is the demoscene around the Commodore Amiga, which was officially produced between 1985 and 1995.

The scene and development of the Amiga are kept alive today by enthusiasts and volunteers who develop new demos, new software, and new hardware for a platform that has not been commercially viable for a long time.

The competitive aspects of the demoscene motivate their members to produce art that circumvents and exceeds the limitations of their chosen hardware. Demoparties are a place of congregation and competition. The fruits of the demo artists' labor are distributed in the scene, but the living memory of the scene are the demo collections and archives.

"State of the Art" by Spaceballs (screenshots)

4. Demosceners as both Hackers and Painters

During it's heyday, the Amiga was a pivotal platform for game developers and gamers. Its affordability and large user base fostered a strong community, sharing knowledge and tools, beneficial for both game development and demoscene projects. The Amiga's hardware flexibility and the availability of various software tools made it a popular choice for creating innovative games and demos. Its legacy in setting new standards in gaming and digital. Let's explore how the demoscene and the gaming industry are connected creatively.

4.1 Games and the Demoscene

The demoscene and computer games, despite their different end goals, share a multitude of similarities. A key likeness is their focus on real-time graphics and sound. Both domains push the boundaries of visual and auditory capabilities of computers.

At the core of both fields lies the requirement for substantial programming expertise. Demoscene artists employ complex coding techniques to generate their stunning effects, a skill akin to that needed in game development. This similarity extends to the creative utilization of hardware. In both realms, there's a tradition of not just using but also creatively pushing the hardware's limits, often going beyond what was initially thought possible.

Artistic expression is another shared aspect. While computer and video games often interweave this with interactive storytelling and player engagement, demoscene productions focus more on the aesthetic experience, prioritizing visual and auditory creativity, typically without the interactive element found in games.

The sense of community and culture extends to both areas. The demoscene thrives on a culture of competition and display, particularly in demoparties. There is a parallel with the gaming world's esports tournaments and conventions. In dome cases, large events like the Assembly Party cover both gaming and the demoscene. This communal aspect fosters a shared sense of identity and belonging among participants.

Historically, both the demoscene and the video game industry have their origins in the early days of personal computing and have evolved significantly with the progression of technology. This shared history underlines a mutual trajectory of growth and development within the digital domain.

Innovation and experimentation are hallmarks of both fields. They have lead to pioneering developments in digital technology, often to groundbreaking advancements in graphics, sound, and interactivity.

While demoscene productions and computer games diverge in their primary focus their similarities show a profound connection rooted in the evolution and capabilities of digital technology.

"Jesus on E's" running on TheA500mini

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

4.2 How Computer Games influenced the Aesthetics of Demos

Many demosceners are also avid gamers, many demomakers work in the computer games industry. Let's tale a look at the aesthetic influence of video games on the demoscene.

Initially inspired by the pixel art graphics and limited color palettes of early video games, demoscene artists have evolved their techniques alongside advancements in game graphics, incorporating more sophisticated textures, 3D models, and lighting effects. This evolution mirrors the graphical progression in video games.

Beyond visual elements, the narrative and thematic concepts prevalent in games have seeped into demoscene productions. While demos are traditionally non-interactive, many have adopted storytelling techniques and themes akin to those in video games, enhancing the overall immersive experience.

The musical aspect of the demoscene also owes much to video games, particularly the chiptunes and soundtracks of early titles. This influence has led to a unique blend of music styles characteristic of demoscene creations, often reflecting the audio trends in gaming.

Moreover, the competitive spirit and drive for innovation in the gaming industry resonate within the demoscene community. Demosceners strive for technical and artistic excellence, pushing hardware to its limits, a pursuit paralleled in the continuous technological advancements in game development.

The overlap of the gaming and demoscene communities leads to ideas, styles, and techniques migrating between the two realms. Demos sometimes reference popular games or adopt stylistic elements from the gaming world. The demosceners' adoption of advanced gaming technologies, including graphics engines and programming tools, has further blended the aesthetics and capabilities of both areas.

The aesthetics of video games have profoundly influenced the demoscene, contributing to its evolution as a form of digital art and shaping its technical and artistic progression.

4.3 The Demoscene, Hacker Culture, and Art

At least a third of the demoscene consists of programmers. They are artists in their own right, and they are "hackers" in the broadest sense of the word. They are not malicious hackers, but rather hackers in the sense of the original meaning of the word: people who are passionate about technology and who are driven to explore the limits of what is possible with it.

Paul Graham explores the similarities between software programmers and painters in his essay "Hackers and Painters". These similarities apply to coders/hackers in the demoscene. Graham asserts that both are forms of creative artistry. He argues that success in both fields requires not only technical skills but also a deep understanding and mastery of tools and materials. He emphasizes the role of creativity and innovation, proposing that just as painters experiment with styles and techniques to create unique art, hackers innovate with code to develop original software solutions. [35] What better blend of creativity and technical innovation can be found than the demoscene?

Graham discusses the importance of aesthetics, noting that it's crucial in both fields—visual beauty in painting and elegance in code for hacking. He suggests that the most impactful work in both domains is driven by passion and intrinsic motivation rather than external demands or commercial interests. Demos serve a solely aesthetic purpose.

The essay further highlights the process of discovery inherent in both hacking and painting. Solutions in programming, much like visions in painting, often evolve during the creation process. He highlights the non-linear and iterative approach to the work. Graham additionally points out the importance of peer recognition in both fields, where the respect and acknowledgment of peers serve as a significant form of validation. Peer recognition is a key aspect of the demoscene.

Graham most certainly did not think of the demoscene in his observations yet they do indeed parallel the work of demosceners who unite the cultures of hacking and painting. They do not just use the tools available to them, they push the boundaries of what is possible with them.

TheA500mini waiting to be connected to power

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

5. The Enthusiasm and Persistence of Anarchist Creatives

The Commodore Amiga's enduring significance in the demoscene is attributable to a confluence of factors that go beyond mere technical capabilities. This advanced hardware made the Amiga an ideal platform for demosceners. Let's close out this essay by exploring the more intangible relationship between the demoscene and the Amiga.

5.1. The Amiga's Significance in the Demoscene

The Amiga's appeal isn't solely rooted in its technical merits. It enjoys a cult status, with a sense of nostalgia pervading its community. This nostalgic value is a potent driving force, fueling ongoing creativity and exploration on the platform. The demoscene, fundamentally about transcending hardware limitations, finds a perfect challenge in the Amiga's now-antiquated hardware. These constraints have spurred a unique blend of technical ingenuity and artistic expression.

Beyond individual affection for the platform, there's a communal aspect to its longevity. The Amiga demoscene boasts a rich legacy, marked by a storied history and a thriving community. Many groundbreaking demos, which have left an indelible mark on the evolution of computer graphics and sound, were birthed on the Amiga. This heritage continues to inspire new generations within the scene.

Moreover, the Amiga's influence extends beyond the demoscene. Techniques developed on this platform have found their way into broader areas of computer graphics and professional media production. This cross-pollination of ideas shows the Amiga's role as an incubator of innovation from an age long past.

The platform's accessibility in the modern era, facilitated by emulators and contemporary tools, has further solidified its place in the demoscene. Enthusiasts can easily engage with the Amiga, creating and viewing demos, thus perpetuating its relevance.

The Amiga is more than just a chapter in computing history; it is a continuing source of inspiration and a canvas for digital artistry within the demoscene.

The user Bane captured the emotional essence of the Amiga very well in a comment on a Hackernews thread: [36]

What made Amigas great was the creative life energy that was weaved throughout it more than any specific technical considerations.

If the Apple Macs were created with the taste of expert graphic designers, and PCs by accountants, the Amiga was made by the kind of anarchist creatives who would later on go to make things like the early Burning Man, perfect the 90s counter-culture digital art movements like the demoscene, off-beat public access videos with the video toaster, the epic Babylon 5, and allow bedroom game coders to absolutely maximize their art.

It was the seed that gave visual representation to earlier cyberpunk.

What a wonderful term "Anarchist Creatives" is! This describes the demoscene so well. Let's take a part the individual parts.

The term "anarchist" here doesn't necessarily refer to political anarchism. Instead, it's likely symbolic of a resistance to conventional norms and structures, particularly in the realms of creativity and digital expression. This could imply a preference for innovation, experimentation, and a disregard for traditional rules of art and coding.

"Creatives" underscores the inventive and artistic nature of individuals in the demoscene. They are not just programmers or artists in the traditional sense; their work often blends these disciplines in unique and groundbreaking ways.

So the "Anarchist Creatives" can be described as individuals engaged in the demoscene who embody a spirit of radical innovation and non-conformity, blending artistic vision and technical expertise to challenge and redefine the boundaries of digital art and programming.

The Amiga waiting for action

(Photo: Marin Balabanov )

5.2. The Amiga is not only a Platform

In their article "The Computer is a Feeling," Tim Hwang and Omar Rizwan proposs that a computer is more than a physical device or a collection of commands and compilers. It is conceptualized as a feeling, characterized by artifacts that facilitate intimate systems of personal meaning, thus shifting the perception of computers from solely technical entities to entities with personal and subjective significance. [37] Let's hold on to this thought and explore a different aspect.

At the end of "Thor: Ragnarok", after Thor and Loki witness Asgard exploding, they realize that the place called Asgard might be gone, but "Asgard is not a place".

The true essence of their homeland transcends its physical existence. Asgard is a people. Their spirit, culture, and unity - that forge its true identity. This thought finds a parallel in the world of technology, specifically within the Amiga community.

Much like the mythical Asgard, the Amiga, a creation of Commodore, faced its own form of destruction, not through physical annihilation but through the commercial downfall of its parent company. However, the enthusiasts and fans, akin to the people of Asgard, carried its legacy forward. Over the decades, these dedicated individuals, driven by passion and a shared love for the platform, transformed the Amiga from a mere piece of hardware into a vibrant, living community.

This transformation mirrors Thor's enlightenment about Asgard. The Amiga, initially perceived as a computing platform, evolved in the collective consciousness of its followers to become something far greater - a community where creativity, innovation, and fellowship thrived. Just as Thor saw Asgard's true power in its people, the Amiga enthusiasts recognized that the true strength of their platform lay not in its physical components, but in the collective memory, shared experiences, and enduring spirit of its community. The Amiga is not a platform, it is a feeling, and it is a community of anarchist creatives.

Both the tale of Asgard and the journey of the Amiga community illustrate a universal truth: the essence of any entity - be it a mythical realm or a technological marvel - resides not in its physical form but in the hearts and shared endeavors of those who cherish and sustain it.

How fitting, that the name of the Amiga, the computer we love and that has united us as a friendly community, itself means "friend".

Marin at Revision 2023

(Photo: Marin Balabanov)

Appendix: The Amiga Demoscene's Notable Works

-

"Red Sector Mega Demo" by Red Sector Inc. (1989)

Watch on Youtube -

"Hardwired" by Crionics & The Silents (1991)

Watch on Youtube -

"State of the Art" by Spaceballs (1992)

Watch on Youtube -

"Jesus on E's" by Anarchy (1992)

Watch on Youtube -

"9 Fingers" by Spaceballs (1993)

Watch on Youtube -

"Desert Dream" by Kefrens (1993):

Watch on Youtube -

"Tint" by The Black Lotus (1996)

Watch on Youtube -

"Rise" by Mellow Chips / TRSI Tristar and Red Sector Inc.

(1998)

Watch on Youtube -

"Rink A Dink: Redux" by Lemon. (2013)

Watch on Youtube -

"Sushi Boyz" by Ghostown (2015)

Watch on Youtube -

"Batman Rises" by Batman Group (2022)

Watch on Youtube

Footnotes

[1] Some scholarly work places the beginnings of

computer demos in the 1960s at research institutes like the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that had access to

computers at the time. Researchers in the fields of technical

mathematics and electrical engineering created applications that

could demonstrate the graphical capabilities of early computers.

They generated 3D vector graphics and developed routines to

shade 3D models solely for the purposes of innovation. Their

developments would later find practical application in 3D

modelling of car components and construction planning.

While these are legitimate demos, the actual demoscene did not

emerge from academia. It began when hobbyists started using the

first home computers.

Botz, Daniel: "Kunst, Code und Maschine: Die Ästhetik der

Computer-Demoszene", Bielefeld, 2011, Transcript Verlag

» Back to [1]

[2] Hartmann, Doreen: "Digital Art Natives:

Praktiken, Artefakte und Strukturen der Computer-Demoszene"

Berlin, 2017, Kulturverlag Kadmos

» Back to [2]

[3] Maher, Jimmy: "The Future Was Here: The Commodore

Amiga" 2012, The MIT Press, Massachussetts

» Back to [3]

[4] Breddin, Marco: "Crackers I: The Gold Rush",

Hannover 2021, Microzeit

» Back to [4]

[5] Polgár, Tamás: "Freax: The Brief History of the

Computer Demoscene", Winnenden 2016, CSW-Verlag

» Back to [5]

[6] Ziegelwanger, Werner: "C64: Aufstieg und

Niedergang einer Legende", Developer Blog, April 6, 2017:

https://developer-blog.net/c64-aufstieg-und-niedergang-einer-legende/

(Accessed on September 21, 2021)

» Back to [6]

[7] Launch of Commodore Amiga 1000 1985 Lincoln

Center USA - Amiga world premiere. Original event video from

1985 on Youtube.

https://youtu.be/UqzapH53q5U?si=xWjm_Fb2vfVJlqGU

(Accessed on September 21, 2021)

» Back to [7]

[8] Decuir Joe; Nicholson, Ronald: "Amiga 1000

Hardware Early History and System Architecture Overview"

http://obligement.free.fr/files/amiga_presentation_nicholson.pdf

(accessed on October 2, 2021)

» Back to [8]

[9] "We Reveal Amiga's 14-bit Audio Possibilities"

https://amitopia.com/amiga-was-already-capable-of-14bit-playback-in-1985/

(accessed on October 2, 2021)

» Back to [9]

[10] Wenz, John: "The Cult of Amiga Is Bringing an

Obsolete Computer Into the 21st Century", Popular Mechanics,

October 3, 2017.

https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/gadgets/a27437/amiga-2017-a1222-tabor/

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [10]

[11] "Revolution: the Video Toaster and the Amiga

computer (Part 1): The original VHS videotape demo from NewTek,

released to promote the Video Toaster card for the Amiga

computer."

https://youtu.be/seznQmDp2pU

(accessed on October 3, 2021)

» Back to [11]

[12] Turkle, Sherry. "The Second Self: Computers and

the Human Spirit. Twentieth Anniversary Edition" 1984, 2005, The

MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

» Back to [12]

[13] Reunanen, Markku. "Computer Demos—What Makes

Them Tick?" Licentiate Thesis, Aalto University, Helsinki, April

23, 2010

» Back to [13]

[14] Mpitziopoulos, Aris. "Computer History: From The

Antikythera Mechanism To The Modern Era"

https://www.tomshardware.com/reviews/history-of-computers,4518-31.html

Tom's Hardware, July 03, 2016 (accessed on September 27, 2021)

» Back to [14]

[15] Pleasance, David John: "Commodore, the Inside

Story: The Untold Tale of a Computer Giant" Downtime Publishing,

Malta, 2018

» Back to [15]

[16] The Retro Hour EP295. Terrible Fire: Turbo

Charging Your Retro Systems

https://theretrohour.com/terrible-fire-stephen-leary-ep295/

published on October 1, 2021 (accessed on October 1, 2021)

» Back to [16]

[17] Big Book of Amiga Hardware. Accelerators.

https://bigbookofamigahardware.com/bboah/CategoryList.aspx?id=6

(accessed on October 6, 2021)

» Back to [17]

[18] AmigaOne x5000

http://www.a-eon.com/?page=x5000

(accessed on October 6, 2021)

» Back to [18]

[19] AmigaOS Supported Hardware

https://www.amigaos.net/content/72/supported-hardware

(accessed on October 8, 2021)

» Back to [19]

[20] MorphOS

https://www.morphos-team.net

(accessed on October 5, 2021)

» Back to [20]

[21] AROS Research Operating System

https://aros.sourceforge.io

(accessed on October 5, 2021)

» Back to [21]

[22] MiSTer FPGA Amiga Guide.

https://makerhacks.com/mister-fpga-amiga/

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [22]

[23] Apollo Accelerators Vampyre.

https://www.apollo-accelerators.com

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [23]

[24] Amiga Forever.

https://www.amigaforever.com

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [24]

[25] PiStorm - Keeping the Amiga alive.

https://www.raspberrypi.com/news/pistorm-keeping-the-amiga-alive/

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [25]

[26] Amibian - Amiga Emulation Environment for

Raspberry Pi

https://www.amibian.org

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [26]

[27] Retrogames Limited. Introducing the A500 Mini.

https://retrogames.biz/thea500-mini

(accessed on October 7, 2021)

» Back to [27]

[28] Revision 2013 Party: "First Time Visitor

Information".

https://2013.revision-party.net/about/firsttime

(accessed on October 3, 2021)

» Back to [28]

[29] Reunanen, Markku. "Computer Demos—What Makes

Them Tick?" Licentiate Thesis, Aalto University, Helsinki, April

23, 2010

» Back to [29]

[30] Reunanen, Markku. "Computer Demos—What Makes

Them Tick?" Licentiate Thesis, Aalto University, Helsinki, April

23, 2010

» Back to [30]

[31] Kopka, Tobias. "Demoscene accepted as UNESCO

cultural heritage in Germany"

http://demoscene-the-art-of-coding.net/2021/03/20/demoscene-accepted-as-unesco-cultural-heritage-in-germany/

Demoscene - The Art of Coding, March 20, 2021 (accessed on

September 22, 2021)

» Back to [31]

[32] Tasajärvi, Lassi: "Demoscene: The Art of

Real-Time", Helsinki 2004, Even Lake Studios

» Back to [32]

[33] Botz, Daniel: "Kunst, Code und Maschine: Die

Ästhetik der Computer-Demoszene", Bielefeld, 2011, Transcript

Verlag

» Back to [33]

[34] Balabanov, Marin: "Shattering the Limits - How

Technical Limitations Pushed the Early Demoscene to Produce

Digital Art", Vienna 2020, Danube-University Krems

(Yes, it's weird to quote myself...)

» Back to [34]

[35]

Graham, Paul: "Hackers and Painters", May 2003, O'Reilly Media

http://www.paulgraham.com/hp.html

(accessed on February 1, 2022)

» Back to [35]

[36]

YCombinator HackerNews thread "What made the Amiga so Great".

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=29962948

(accessed on March 7, 2022)

» Back to [36]

[37]

Hwang, Tim; Rizwan, Omar: "The Computer is a Feeling"

https://github.com/timhwang/nyrc/tree/main

(accessed on May 12, 2023)

» Back to [37]