Dots by Any Other Name

III. The Production Process

To destroy is always the first step in any creation.

- E. E. Cummings

For the purposes of this paper, it is of great interest to compare the process used to create Shatter with the process used most commonly in American comics of the 1980s and then juxtapose that with the process used nowadays (2018). This will show how much Shatter deviated from its contemporaries and allow us to investigate how much of its production process can be found in today's comic books.

The Typical Process in the 1980s

The writer of the comic typed the story and the script on his typewriter and sent it to the editor for review.

Once approved, this physical script went to the penciller, who sketched the rough layout scribbles of the 22 individual pages. These were much smaller than the original artwork or the printed page and served for design purposes. Then the penciller drew the actual pages (usually at double the size of the printed page) with the figures, the props, and the background scenery or locations.

In some cases, the penciled pages were returned to the writer who then provided the script for the captions, dialog, and thought balloons. In other cases, the script already had all the captions and dialog when the penciller received it.

In the next stage, the letterer drew the caption boxes, speech bubbles, and thought balloons to then place the letters in them.

As soon as the penciled and lettered pages were completed, they were sent to the inker. They redrew the penciller's art by tracing the lines—providing them with weight, cleaning them up, and giving the solids some texture. The inker made sure that objects in the distance were drawn with a faint line and closer objects or characters were drawn with the full weight they needed to tell the story.

Finally, the colorist applied colors and tones to the artwork by hand.

The pages of the comic book are then photographed for print and reduced to the desired size[13].

Figure 21: MacPaint on a monochrome Macintosh (ca. 1984).

The Process used for Shatter

The digital workflow of Shatter also starts with the script. But as described by Mike Gold, the series' editor, in the editorial of Shatter Special #1, "... Peter would dialogue Mike's art on an Apple III, but it would be lettered on the Mac."

In Shatter #3, Editor Mike Gold continued to describe the process: "Virtually everything in Shatter, prior to the coloring phase, is generated as Apple Macintosh MacPaint computer files and then printed on an Apple Laserwriter."

And further in the editorial of Shatter Special #1:

Together with First Comics' production manager Alex Said and editorial coordinator Rick Oliver, we agreed that every aspect of Shatter would be performed on the Mac - the art, the lettering, the logo, the advertising, even this editorial. Everything but the color. We could create the color on the Mac (and we could come up with some interesting effects by creating a wider range of tones) but it would take far too much time.

Figure 22: Interior story art from Shatter Special #1, colored (left) and before coloring (right).

So, the process used for Shatter saved on transcribing the script and on producing the pencils to be inked because the artwork was drafted directly on the computer. The coloring as the last step still maintained the established traditional workflow and did not save any time in this respect.

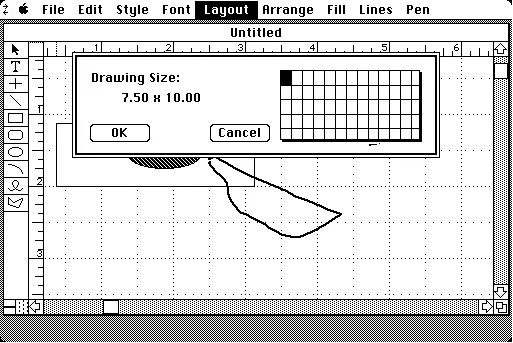

Figure 23: MacDraw on a monochrome Macintosh (ca. 1985).

The Typical Process in 2018

Today, we need to distinguish between comic books produced by the "big two" commercial comic book publishers, Marvel and DC Comics (and to a lesser extent, the next large publishers Image and Dark Horse), and those comics produced by independent artists or groups of artists.

Commercial Comics

Even at the time of writing this paper, the steps in creating a physically printed commercial comic book have not changed drastically compared to 1985, but the process is greatly expedited. A writer writes the plot and the script and sends it as an email to the editor who then provides all the changes and forwards it to the artist.

This where the process becomes very disparate. Different artists work differently. Some will still draw the artwork on paper board using a pencil and then either ink it themselves or pass it on to an inker to be embellished. Even if this analog path is chosen, some artists will still use digital references or even trace from printouts of digital sources. They might model difficult background shots using 3D software and then draw from this reference. In any case, the artwork is scanned into the computer and sent as a digital file to the publisher for further processing.

Two steps in the process have switched nearly exclusively to digital: lettering and sound effects and the coloring of the book.

Figure 24: An artist using a Wacom Cintiq 24"

(Source:

http://www.antcgi.com/2014/05/27/thoughts-on-the-wacom-cintiq-24hd/)

While a large part of the drawings for commercial comic books is still produced using analog means, the tendency to produce purely digitally is slowly prevailing in independent comics. Artists either draft their artwork directly on a screen using a Wacom tablet, Microsoft Surface, or iPad Pro or they sketch on paper and refine their work digitally. Some artists use 3D software to meticulously render their characters, props, and backgrounds. Then they combine the components using paint or layout software.

That being said, commercial superstar artists like DC Vice President and one of the current Superman artists Jim Lee and Green Lantern artist Ethan Van Sciver still pencil and ink their work[14].

Even though exceptions do exist, to this day, the mainstream process is still not fully digital with analog steps remaining for drafting and inking. The process of coloring and lettering are fully digital. One of the reasons for the pedantically segmented process in commercial comics is strict editorial control over every step. This not only allows the editor to play gatekeeper, catching any potential quality issues or any part of the commissioned work that might be inadequate or inappropriate, it also allows the editor to keep an eye on the progress of the comic book from the first word laid down to the finished piece being delivered to the printer.

Strangely, this only partially digital production process needs to end in a digital file for printers to handle. Even though the sales of physical comic books are dwindling in 2018, digital distribution of comic books through vendors like comixology.com cannot yet compensate for the drop in sales.

Independent Artists

Again, it is hard to generalize; there will always be artists who prefer traditional analog means. In some cases, they might not even use pencil and ink on paper but could use a completely different analog media, such as oil on canvas or collage or any of the multitude of different techniques established over the centuries.

Independent comics artists often work alone or, at most, in a small team. They mostly do not have a support infrastructure, so they do more on their own. This is one of the reasons why digital production is more common in the field of independent artists.

Due to the lack of editorial control, the process does not even always need to start with a ready plot and script but can start with sketches that evolve into a complete story. But for the sake of comparability, let us start the digital process an independent artist uses with the story creation (plot and potentially script). They then might produce thumbnail layouts of the pages to get an idea of the story flow and the necessary number of panels. This might be done on paper or, already at this stage, on the computer.

Then the digital artist completes the final stages with digital tools. Outline art might be drawn similarly to previous techniques with a sketch, a finer rendering of the sketch in more detail, and then the final cleanup. But because they are working digitally, they are not bound to the processes of physical media.

After rendering the outlines, the color art can be produced without delay or the need to change medium in the next step. Lettering and sound effects are added. And the page is done.

Purely digital pieces can be distributed over the web; those produced for print can be emailed to the printers for direct printing.

Figure 25: The Smith Micro application Poser allows artists to pose 3D charactersand render them out as ink drawings for use in their comics.

Comparing the Processes

In contrast, Shatter was limited by the available means of communication, with disks with the digital materials being mailed conventionally. But save for this, the whole process was digital. The limitations of the printing presses made it necessary to produce a hardcopy of the line art so that it could be photographed for the plate-based offset printing of the day. Coloring solely on a computer was not yet feasible on the machines available in 1985, remaining a task to be done by hand the traditional way.

Footnotes

[13] Lee, S., & Buscema, J. (1978). How to Draw

Comics the Marvel Way. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc.

» Back [13]

[14] Ethan Van Sciver's YouTube channel:

https://youtu.be/uLKufn1IPcI

and

https://youtu.be/f4hSPJxN3nc

» Back (14)